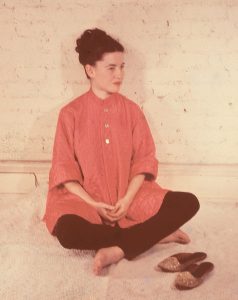

My mother was a beautiful woman. Full stop. She had straight hair, almost black (in 1920s Nebraska she and her sister Julie, surrounded by Scandinavian and German blonds, were always tagged to play the “Oriental” characters in geography pageants) and expressive brown eyes with a slight epicanthal eyefold which made her look a little exotic. And the bone structure, O! the bone structure. My father could still, years after her death, talk about how beautiful she had been (this despite the fact that the last 20 years of their marriage had been hellish for both of them).

She was also funny and smart, charming and loving and deeply troubled. For the second half of her life she was an alcoholic whose anger at the world drove her to slow self-destruction, a sort of “see! Look what you’re making me do!” message to the people who loved her. I suspect the alcohol was the best she could do to manage a life-long anxiety/depression disorder, but when you’re a teenage girl taking almost the full brunt of the anger of a highly verbal alcoholic–well, that didn’t make it any easier. Whatever I wanted to be when I grew up, it wasn’t my mother. Except in looks.

It was an unspoken truth: in my family my mother was the standard of beauty. I, however, take almost entirely after my father’s side of the family. I recognize now that my paternal aunts and my grandmother were lovely–photos I’ve seen of my Aunt Eva in her 30s show her cut from the lush Ava Gardner mold–but somehow that wasn’t what was wanted. No one said anything to me specifically–“shame you took after the wrong side, kid,” but the message must have been there, because I absorbed it. Almost 70 years later, I struggle with feeling that it’s somehow my fault, as if I chose to take after the wrong side of the family. And because I’m neurotic, I wasn’t content with not looking like my mother, or not being pretty by the standards of the day (late 1960s–think Twiggy and Jean Shrimpton), I assumed that I was ugly, and that it was my fault. My looks were a moral failing.

It wasn’t helped that I got little incentive to believe otherwise: my father, in matters of aesthetics, could not put aside his absolute truth in favor of affection; I overheard someone say “Madeleine is beautiful,” once, and his immediate rejoinder was, “Madeleine? Madeleine’s not beautiful.” Whatever the speaker saw, my father couldn’t even say “thank you” and let it lie. He heard an error and had to correct it. I think my father would have been delighted if I’d looked like Mom and my brother had looked like him–what mattered in his son (to my father) was a carrying on of his artistic skills and vision, and he got that. But my brother also got my mother’s eyes and bone structure, for which I WILL NEVER FORGIVE HIM. Ahem: he’s also a really good guy, and abundantly talented.

I was told by someone in high school that “you act like you’re pretty but you’re not.” I’m not sure what the basis was for the statement, but this much is true: I’ve spent my life acting as if I were pretty and making a fair go of it. Then I had daughters. They are uncomplicatedly beautiful, each in her own way. I’ve made it my purpose in life (one of them, anyway) to make sure they know it. One of them looks like me, which has caused me a certain amount of cognitive dissonance: how can I accept that she’s beautiful when I have all these wobbles about my own looks? Granted, we live in a society where images of the current definition of perfect are everywhere; it’s in the interest of influencers and cosmetic companies and magazines etc. to make us all uncertain about our own appeal. It takes a stronger woman than I am to completely shut it out. And that daughter who looks like me? Has spent hours of her adolescence and adulthood watching grooming videos and keeping au courant with makeup trends and… So she’s not immune to it either. But she does not appear to have fallen prey to my “If I Don’t Match the Dominant Paradigm It’s Because I’m a Bad Person” psychosis, for which I am abundantly grateful.

So here I am, pushing 70 and daily more aware that there’s no chance of a do-over where I can opt for Mom’s genes over my father’s. I understand, with the full force of my intellect, that I’m not scare-the-goats ugly. I’m even attractive. Like my mother, I’m funny and smart and charming (sometimes, anyway). I accept, also, that what I look like (beyond niceties of grooming) has nothing to do with my moral failings or triumphs. Mom died at 62–a victim of smoking and drinking and her own anger, which was a product of her anxiety and depression; it took me years to get over seeing those behaviors as moral failings rather than the symptoms they were.

I look in the mirror and see an older woman with the marks of her years and her experience, with humor and adventures and mistakes and the odd triumph here and there. If I get an occasional echo of “it’s your fault you’re not…” whatever, well, this stuff lodges deep. I expect I will get those echoes until I die. But they’re echoes. With luck and attention they will keep growing fainter with time.