This last post is very long. It’s also a bit less clear than the earlier ones. I was going to explain the current meanings of Zionism, updating the previous post. Interestingly, so many people have their own views of the definition and want to correct even the groups made from nearly two hundred opinions. Instead of giving you cute names attached to views of the word ‘Zionism’ (I so wanted to include Mountains of Madness Zionism) I’ll begin with a quick revision that allows anyone to slot new thoughts into the three groups.

Anything that prioritises Jewish definitions of a Jewish concept is going to describe Zionism as related to the state of Israel. Alas, this includes those arguing that it should not exist. Why the ‘alas’ – because all arguments about its non-existence either fail to take into account those who want all Jews dead, or actually celebrate all Jews dying. If they would solve antisemitism and violence against Jews before inventing a county where Jews cannot live, I would have more sympathy with them. If they lived in 1938, they would be helping the building of death camps either literally or socially. When I tried to talk with some of these people, they fell into two groups. One believes that Jews have not really been murdered, ever. The other believes that we should all be murdered and that Israel is a good start. Accepting that Zionism refers to Israel existing is not quite the same as Zionism referring to Israel as a Jewish state that should exist. Many of those who support Israel are now explaining that second part (that it has a right to exist, that Jews need it, that there are ancient links to the land) to distinguish themselves from those who try to have their cake and eat it to, by saying that yes, Israel exists, but it should not.

This is actually not as muddy as I made it sound. If all Jews are to be killed, then Israel doesn’t exist. Using ‘Zionism’ in this way is a false claim. I now try to work out from other things a person says if they give Jews equal rights to other people. That helps explain whether their acceptance of Israel as a country is temporary or false.

In some cases, the thoughts can be attached to groups two and three together. Hate seeps into everything once its become part of general conversation. I can’t explain this as well as I should, because every single person I’ve found who uses the second group of definitions of Zionism with the hate and mirroring from the third… blocks me quite quickly. I’ve looked around, and I’m not the only one blocked and the blocking is not restricted to Jews. Iranian Diaspora activists are also blocked, as are general supporters of Jews and Iranians. Those who combine the second and third group of definitions are creating their own echo chamber. This worries me.

As I said last post, there are an increasing number of personal definitions of Zionism. I’m not even going to try to make a complete list. They still mostly fall into the categories I established last post, so the best thing to do is to categorise them and find out what the person explaining Zionism thinks and where they fit politically and on the hate spectrum. Otherwise we argue about minutiae and the problem of hate ferments all by itself in the background. Also, identifying the groups of definitions helps anyone who is subject to the hate to identify it quickly and address it in the best way for them. For many, this means hiding from the bigots, because there is so much violence attached to certain parts of both the second and third groups of definitions. In others, it can be talking things through and finding common ground. How to deal with local hate would be a whole new post, though. I’ve done it all my life (including advising those in politics, the public sector, and in community organisations deal) and am willing to talk about these things, but not here and not today.

So what am I doing today?

I am about to give simple explanations with simple examples of some very complex stuff. This is only a blog post, after all. I could write a book on each of these, and then another explaining how it all holds together and the history behind it. I am not going to write those books. The book still seeking a home (the history one) shows how we are given narratives that support all the things I’m about to talk about. This post, by comparison, is me dipping my big toe in the water, just to show you that there is water. I’ve done it in form of a series of points, because I am running out of time. Other weeks I’ve had hours to spare, this week I have editing and deadlines and possibly will find time to get dressed later today. Possibly.

The series of points

1. Zionism and its related words rely on a fabric of understanding. Not all Zionists are Jewish, but all Zionism is linked to Judaism. It’s one of the words and sets of ideas that connect Jews to the non-Jewish world.

2. We learn about what the world thinks about us from the way groups or individuals use words related to Judaism. I was told just yesterday that I had tikkun olam entirely wrong… and also two thousand years of historical Judaism. This was from the third person in two days who knew a little, but not enough to know what they did not know. Even with the best intentions, telling someone that they don’t know who they are and that everything they know since childhood is wrong… is not kind. There is a lot more to the ‘splaining and erasing Jewish knowledge of ourselves than the unkindness it manifests.

First, as women discover when we are mansplained, that kind of explanation indicates, to the person doing the ‘splaining, that Jews (or women) are secondary. Less important people. Children who have to be told things because we cannot think for ourselves.

With Zionism, this produces a really interesting quandary. As I said earlier (in different words) some people who use the standard definition of Zionism (Israel’s existence) are anti-Zionist for the same reason they ‘splain. In their minds, Jews are not capable of running our own lives or even knowing our own religion and culture. If we lack the capacity of adults, how could there possibly be a Jewish country?

This is an old form of antisemitism, where Jews are considered to be better off subservient. I know its European origins, but the dhimmi system also implies religious immaturity and gives secondary status to Jews. It’s for our own good that we are told things and that there should be no Israel. We’re not mature enough yet. Or are just made to be ruled by others, especially others like the person ‘splaining.

3. Another link is made by those who have not directly experienced antisemitism. In their eyes, others must be exaggerating for attention. This is where the accusations of playing the victim card and pearl clutching enter. The sense that this can’t be right (too dramatic, or “I don’t see these things”) proves the antisemitic trope of Jews being liars. Perceiving Jewish hurt as false cements antisemitism in many peoples’ minds. The best equivalent I can give is the attitude some men have to child-bearing as painless and natural. Lived experience is not considered relevant in either case.

4. ‘Zionism,’ ‘Judaism’ and a bunch of connected terms are also triggers for people to erase others from their lives. Many of us have lost whole social circles in the past two years, simply because of non-existent Jew cooties. I say “I’m Jewish” and some friends say, “You could not tell anyone” and others disown me for being public about it. I’m a “bad Jew” for making those words mean the wrong thing.

5. This leads to Schrödinger’s Jew, where it’s fine to be Jewish or have Jewish ancestors as long as nothing is visible publicly and there is plausible deniability. Jews can march with other pro-Pals as long as no magen davids are worn and they eat bacon and don’t talk about their Jewishness. This relates to the silencing of most Jewish voices, especially those from the Jewish left. Certain Australian writers’ festivals are really good examples of this.

6. Many bigots say, “We’re hurting too.” Other people have suffered awful things. These people of course need our support and help. That’s not what I’m talking about. I’m talking about the deliberate destabilising of discussion about Jews, Israel, Zionism by changing the subject. This can be gaslighting.

7. More everyday, is when people refuse to learn about Jewish stories or culture and then fill the artificial vacuum with stereotypes and an understanding of Judaism drawn from Jew haters. This is related to whether Secular Judaism/ Jewishness is seen as an ethnicity or simply a name tag. There are secular Jews, but this is not them.

8. Some people use a modified set of terms to indicate some rather big things: Jews as a problem, the West as a problem, settler colonialism as a problem, for instance. The style of terms is “Zionist entity” instead of “Israel” or “So-called Australia” instead of “Australia.” Sometimes this comes from far-left people and shows hints of Marxism. Sometimes it comes from those who listen to the spokespeople for organisations link to the Muslim Brotherhood. I see this as indicating that some of the far left may be linked to the Muslim Brotherhood. This may be linked to the groups and collectives where there’s not a lot of shared understanding of Judaism, but much support for Hamas. It also can be linked to using language from DEI, Critical Race Theory, and is often shared by BDS folk in my vicinity.

9. Dehumanisation of Jews. An oldie but just as nasty as it ever was. Watch for how haters talk to Jews and about Jews – check that we’re still human in their eyes. An example from X: Leon Knight @KnightLeon34974 wrote “I don’t want my kids to suffer any kind of religious indoctrination in their education, but especially not from a satanic death cult like Zionism.”

10. Performative stuff, using slogans and banners and marches tends to (because of its nature), play favourites. One of the worst things about this is that the kindness and support for underdog some shouters claim (I suspect this might include Grace Tame in Australia) is an image and not real. I always look for more than the slogans to find out how people reach those slogans. Almost always, in the case of matters relating to Judaism and Israel, they reflect many of the things I’ve just listed.

11. Statements that look obvious, but that are part of a silencing. “Gazan voices are being hidden” is one of the more interesting statements, because it’s partly true. Very few non-Hamas and non terrorist supporter voices from within Gaza are heard – but those voices are not the ones protested about. Randa Abdel-Fattah and Omar Sakr claiming that they themselves are silenced in Australia and that Jews have loud voices are a more useful example.

All of these elements can lead to a lack of context and destroyed narrative. More and more people think they know about a subject and they really, really don’t. This makes hate much worse. There are also rhetorical devices that make hate worse by reinforcing certain thoughts or by spreading them. I don’t have time or energy to give you a complete list and big explanations of these devices. I’ll give another list, I think, just so that some of them are more visible.

When people tell hate stories, these are some of the techniques they use

1. Repeat and repeat and repeat an idea or a word. When you say it often enough, then most of us stop arguing with it. This is why marches include slogans and accusations and chants. It’s also why so many interviews of those marching are hilarious. When a marcher only knows the repetitions, they find it difficult to answer questions about why they march.

Query constant repetition and find out what story it’s telling.

In the case of ‘globalise the intifada’ and ‘from the river to the sea’ those who shout it also say that the meanings are benign. There are two sensible approaches to the claim of benign meaning. The first is to look into historical uses of the terms eg if people were killed when other claims of intifada were made then the use is violent and the claim to benign meaning is false, for instance.

The second is to find out if those who insist on using the terms have used others, with less fraught ancestral use. An Australian example is whether anyone shouting ‘globalise the intifada’ has thought about the relationship of the Bondi shooting or of the death of Malki Roth and whether they have changed their language to not hurt the families of those killed. If they haven’t used other terms that don’t hurt people… then those terms are not benign and they’re using the lie of them being benign to spread hate. The best answers to questions about repeated words and what the users intend, then, is in the use of the words, both historically and currently, and also in whether the users are willing to change things so as not to hurt anyone.

2. I know my favourite tool from Medieval French epic legends. Roland was always ‘the brave’ and Olivier was always ‘the wise.’ If you put a single adjective in front of a noun incessantly for a time, then eventually all the people who see it will include that adjective as part of their understanding of the noun. Trump does this all the time. So do antisemites. “Evil Jews”, “genocidal Israel”: no proof, no argument, just the identification of the word with the thought so that we can’t help thinking about a thing in those terms.

This example of “vile Talmud” from 22 February gives exceptionally good context for why ‘vile’ is a problem. “Ashkenazis are such annoying war mongers who follow the vile Talmud that condones the rape of 3 year old non-jewish children. The problem is that even if you murder another 1 million people you will not feel ‘safe’ as you know your time is linked to US support and you are thieves” 3:37 PM · Feb 22, 2026

3. Claims without evidence are true of many bigots in history – saying something does not make it true, and running away when people ask for evidence is one of the ways of discovering there is no evidence. The most common one in my timeline right now is people talking about Israel’s live-streamed genocide. Not a single person I’ve asked (or others have asked) has proivided any link to the live-streaming. Some duck and run, while others say “It’s so obvious, find it yourself.”

4. This links back to my earlier list because it’s to do with how we see words. Some people cannot or will not explain the words they’re using and then say “You know you know this” are adding to hate by creating fuzzy (and negative) definitions. When I ask and explain that I’m looking into definitions and word use, I often get some really interesting examples of Jew hate. This is something that looks innocuous, but may not be.

I don’t assume that lack of knowledge = hate. I find out if the person can and will explain without falling into hatespeech before I make any decisions on this. In other words, there are people who genuinely don’t know standard definitions and are willing to talk. We may not agree at the end of the conversation, but they are not spreading hate.

5. This has come up before: episodic memory, where brief anecdotes take the place of historical understanding.

And this is the moment where we move beyond rhetorical devices and into knowledge-based issues.

6. Bringing debunked knowledge into play and denying scholarly work on the subject. Khazars, genes, that no modern Jews have ancestry in the pre-Roman Levant, that all Jews are converts, that all Jews are… all kinds of things. The blood libel is one of them and I was blocked by someone claiming the 12th century story as true. Others weren’t blocked for arguing, so I suspect that my PhD in Medieval History was what got me blocked.

7. Who we believe. I’ve noticed, for example, that Amnesty tends to believe Hamas over the Israeli government. The solution for this is to be a critic and scholar. Look at all the evidence. Don’t trust simple data. Not from Amnesty, not from the Israeli military, not from anyone. Question it. Question it deeply and profoundly and very, very critically.

One of the reasons Hamas does not get questions and their clear statements that they prefer their Jews dead are accepted is because of that mirror I mentioned in the last post. Hate gets reflected onto Jews and therefore the assumption is that all Jews are murderers and Hamas is a resistance movement. This is why we all fatalities in a given day attributed to the Israeli army on social media, while the (non-Israel) observers say “Hamas killed 20 people from a family that opposes it” and those fatalities are still attributed to Israel by most media. We don’t know how many people were killed by whom… hence the need to question.

8. Jews as aliens in all places. This is enhanced by how many stories are framed. eg SBS Australia leaves Jewish food off its food page except for certain select recipes. There are no regular articles or recipes, but there are for other Aussie minorities. (SBS is the multicultural broadcaster, so this goes against one of their core values.) And… this is what the book is about, the one I need to find a publisher for.

9. Jews having ‘hidden motives’ – even the most literal person (that would be me) is told regulatory “You don’t mean what you say. You’re hiding your secret agenda.” This is closely linked to those forcing Jewish culture to be hidden, obviously.

Much hate is being couched in very precise language eg previous post and the differences Zionist/ism can have. Much hate revolves around whether Israel should exist, whether Jews should be allowed to live but hidden under “We support those who are being hurt by evil” ie Gazans/Palestinians. Defining that hate and defining Jewish concepts that help reveal that hate (see previous posts) helps us see whether the conversation hides the hate or whether it’s less or even non-problematic. I have had good conversations with supporters of Gazans where those supporters do not use the 2nd and 3rd groups of definitions of Zionism ie do not bring antisemitism and antizionism into the conversation. Identifying this can be as simply as seeing if Zionist/Zionism/Israel/Jew are used pejoratively.

The three most obvious paths for identifying this are:

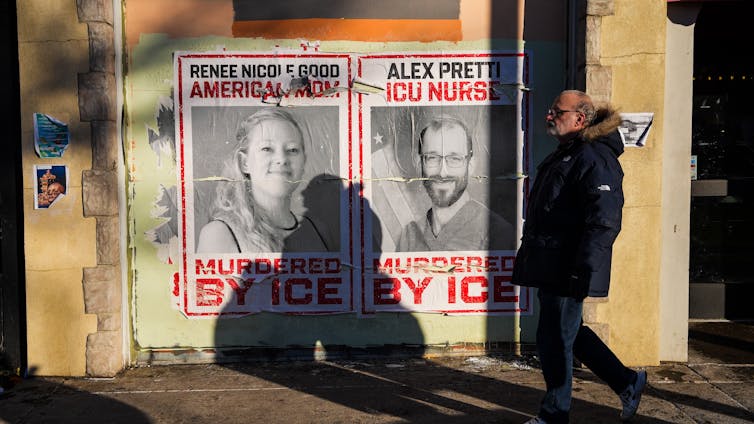

1) through the David Duke use of zio and its descendants, such as ziofascist, which I tend to think of as ziomostthings. The hate in the doxxing of Australian creatives in 2024 was really clear, for instance, because they were called the ‘zio600’ by haters. Some of those haters sent death threats. When name-calling stops being passive, then we’re all in trouble;

2) Through the Nazi terminology and evoking Nazi history. Last week I saw “Your grandparents were lampshades and soaps” three times, but more common is “You should be dead.”

3) Through the Protocols and its various descendants.

Adam Louis-Klein talks about us entering the antizionist era. His work and the work of those who talk with him and about his work is documenting the changes he observes. I don’t always agree with him, but I’m not going to do a giant summary of either his work or my thoughts on it. I’m not even going to give you a small summary. Instead, I’m going to suggest that he and his circle are lucid and thoughtful and worth looking into and forming your own opinions about. What is important right now, here, is what his work does to words like ‘Zionism.’

Right now, uses of ‘Zionism’ can be generally grouped, but within that group there is total mayhem. We’re moving past this moment of total mayhem (and he is one of the reasons why), and into new definitions that are shared by some and other definitions that are shared by others. Diacultural groups are changing, day by day.

Some of the constructs of hate will adapt to meet Louis-Klein’s work (and that of others – he’s an example, not the only scholar in the field), because they are challenged by them. The second group from the third post (that sounds so strange) will change even more, because Louis-Klein and company are uprooting their work and bringing it into the clear light of day. And some won’t care, won’t look.

The propaganda arm of whoever is propagandising will find other ways of sharing hate for Jews for as long as we’re a handy target. And as long as antisemitism exists, we’re a target. It’s nothing to do with Judaism (as the Zionism definitions show) and everything to do with pushing this society or that in this direction or that. When people decide not to be pushed in that direction, the hate diminishes.

This week, quite a few antisemites preened and gently threatened in my direction. More public Jews (I’m only semi-public) get regular and very nasty direct threats. There is an element of narcissistic show-off in Jew-hate, and that element has led many people into dark places since October 7. It has also caused many people to move gently away from once-friends who happen to be Jewish, lest the Jew cooties infect.

The microcosmos of antisemitism is like a teenage schoolyard in a really bad school, with bullies and mean girls and that boy who jumps off the roof because he wants to show off.

I am volunteering twice a week at an elementary school in downtown San Francisco, and enjoying it immensely. Part of what I enjoy is the roughly ten minute walk from BART to the school, which takes me through a somewhat rough neighborhood which is slowly turning around. There are a couple of nail salons, and a couple of coffee shops, one of which I have been eyeballing since I first started volunteering in October. I haven’t been in yet, and today I realized why I stare wistfully at the door but don’t go in. It’s partly a Me thing, but partly a Them thing.

I am volunteering twice a week at an elementary school in downtown San Francisco, and enjoying it immensely. Part of what I enjoy is the roughly ten minute walk from BART to the school, which takes me through a somewhat rough neighborhood which is slowly turning around. There are a couple of nail salons, and a couple of coffee shops, one of which I have been eyeballing since I first started volunteering in October. I haven’t been in yet, and today I realized why I stare wistfully at the door but don’t go in. It’s partly a Me thing, but partly a Them thing. The other night I took a two-hour class in darning, which is how you repair holes in fabric. A couple of weeks ago I took a class in sashiko, which is a Japanese form of making decorative patches to repair clothes.

The other night I took a two-hour class in darning, which is how you repair holes in fabric. A couple of weeks ago I took a class in sashiko, which is a Japanese form of making decorative patches to repair clothes.