Very few people wonder how those of us whose bodies are less capable of doing this or that get anything done. I am a very good illustration. I had glandular fever (mononucleosis to my US friends, I believe) in my mid-twenties and developed many of the vile long-term symptoms that people currently associate with Long COVID. In other words, I’ve had similar symptoms to Long COVID for nearly 40 years. This is not the only problem I’ve faced in my life, nor, indeed is it the biggest. It’s certainly the one that has invited the least inquiry. And the least understanding. Today I want to talk about how I’ve achieved anything at all in a life where I cannot guarantee even an hour without fatigue and pain. The physical side of it is one story and I don’t want to talk about that today. Today is, you see, an exhausted day, when I should be in bed wondering when I will improve a bit. It’s not a day I have to be in bed, however – those days when any exertion at all just makes things worse have become rarer as time passes.

I lost my time sense last night. That is, to me, a signal I need to live my alternate life. This post is brought to you from this alternate life. It’s a half day later than usual because I had to wait until I was able to do it.

This is how I handle days like this. If others have needs I fit in with them, but the next day is worse if I fit in. I suspect Friday will be a bed day because Monday night and Tuesday nights are brain fog days (with occasional windows of opportunity, one of which is right now), Wednesday is full of meetings and Thursday is full of unexpected medical stuff. I didn’t expect Wednesday and Thursday to be the way they are, which is how I can predict Friday. One thing I’m doing to prepare is (with the help of a friend) a big shop. One of the things I will be getting is reheatable food for Thursday to Monday. On Saturday I knew that yesterday and today would be a bit of a struggle, so on Sunday I prepared food for both days. This planning is constant. And I don’t always have the energy to do it.

There’s a lot of body-awareness and a lot of planning to get through the everyday and when one of these fall through things are like a deck of cards and I have to stop and start all over again. Currently I have enough income so that if the cards all fall down, all I need to do is drag myself to the computer and order enough home delivered food to get me through. Or open a tin from my cupboard. I lived on dolmades for 3 days recently, then I advanced to chicken and chips, because that was the easiest option and I wasn’t up to more. Then I was through that phase and was able to cook again.

Knowing I’m exceptionally busy on other peoples’ schedules this week means I can plan in advance. When anyone tries to spring something on me, they can set me up for a whole week of not being able to deal and I will hide it, generally, but there are people I really do not like because they never check if I’m able before springing things on me. If I had energy on the worst days, I could explain to someone who says “I have to see you” that it has to wait because I’m unwell. In fact, I do explain “I can’t do it now because…” but I can’t get into detailed explanations. Exertion can hurt and sometimes the little things like explaining (especially if there’s emotion attached) can hurt more than the large. This is why, oddly, the chronic fatigue is more of a problem in my life than more serious problems are.

The other thing that happens when my time sense gets derailed is that I drift off into byways. The path this post has taken is one of these byways. I meant to launch straight into “This is how I get novels and non-fiction written and research done and achieve as much as some people who have never had any sort of debilitating illness.” I think the tide of emotion carries my life forward at these moments. This post is an excellent example, in fact, of how this happens.

I use emotion to get work done at times like this. I sat down at my computer to write this post, having no idea what I’d write about at that point. I saw my research document open on the desk and just took a look before opening a new file. I edited three paragraphs. It wasn’t a lot, but over a week (even a really bad week) this adds up. Then I stopped and thought, “Why did I do this? Why didn’t I go straight to the blogpost?” My answer was, “It’s one of those weeks” and then “But I should tell people”. Because the sense that something is important gives me enough fuel to write. I will sit down quietly for a half hour as soon as this is posted, and then I’ll go shopping with a friend and make sure I have food for the coming life-sapped time.

I’m the sort of person who would rather work methodically, so when I’m less beleaguered, all my work is done entirely sensibly. On days like today, I allow the wind to carry me along, and take advantage of the moments I have. Little things, done when I can. That’s how I deal with the fatigue and the near-constant pain. I factor in the physical work I need to do to keep going and, month by month, I deal. I write whole novels this way, and do my research and when I can’t do anything except sit or lie down, I think things through. Slowly. My brain stutters at times like this. It’s bad for quick thoughts and insights – it’s wonderful for deep and slow unpinning of complex problems.

A few years ago, when I realised my strange lifestyle, I found a way of describing it. That description was more useful to friends who asked “Are you OK?” than to people like the one who emailed me a the start of Yom Kippur last year, and who wanted to meet urgently. It was a week far worse than this and I wouldn’t be up to a face to face meeting for weeks. I lost my Yom Kippur over that email and lost some days after it. The person who emailed would not have understood this from my metaphor. I needed more capacity to explain than I had… some situations are simply impossible, still.

My metaphor is not a new one. I say that life throws me garbage and, bit by bit, without pushing myself into more illness, I turn that garbage into fertiliser and it grows me the nicest garden. All my published novels are flowers, and Story Matrices, the book that has just been short-listed for the William Atheling Jr Award, is a rather nice rosebush. That book was written in a shockingly bad year, but the editor, Francesca Barbini, knew this and worked with me according to my actual capacity. She didn’t try to make me into something I’m not. She helped me create the best thing I was able to create in a year from hell.

Every paragraph I edit and every thought I have transforms this strange life into a strangely interesting life. Chronic illness isn’t the end of things… it does however, change things. And most people won’t ask or won’t know or won’t care. That’s part of the garbage being thrown. That garbage can be isolating and it can be depressing, but it’s excellent fertiliser.

Now all I need to do is find a publisher for the novel I wrote when I wrote Story Matrices. It’s the fictional approach to this isolation and strangeness and is a very different COVID lockdown novel to most. My way of dealing with the difficult is rather like a portal fantasy, you see, where you open doors briefly and visit worlds you can’t remain in because remaining is dangerous. My COVID novel is a quietly adventurous version of the portal novel that is my life. Glenda Larke (a friend with a marvellous new novel) was my beta reader and she told me that it was the best love story that she’d ever read. It needs a home, but writing it was the accomplishment. Just as the publication of Story Matrices was an accomplishment. Just as editing three paragraphs of my research and writing this blog post are accomplishments.

Chronic ill health isn’t the end of things. It does, however, require a series of reinventions of self, and the ability to say “If this is all I can do today then that’s fine.”

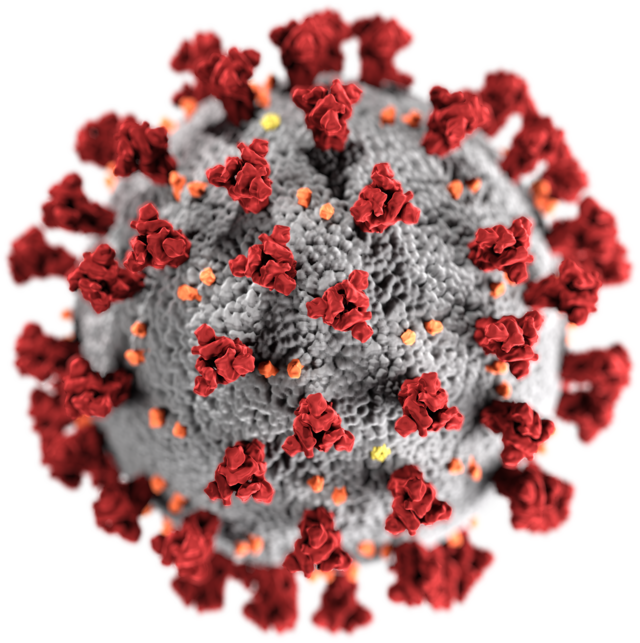

Why am I telling you all this? Because Long COVID is not going to go away. Some people will recover and some won’t. It’s quite likely you know someone who needs to know that this kind of chronic illness is not that end of world and that, over time, some extraordinary things are possible. They probably also need to know that the vast majority of folks around them will not see or even want to see what the new life entails.

Adjusting never stops. Seeing your own needs is essential. And once you know what your signals are (in my case, that loss of time and that drifting brain and the need to dump my once-wondrous rationality) and how to handle them (when to push, when to let things slide, how not to live on chips) life can become a lot better. Your garden will be all the better for the fertiliser. It won’t feel that way, however, because no matter what you do with the garbage being thrown at you, it’s still garbage. I’m still learning to celebrate the flowers and not be personally affronted at the garbage that is thrown in my direction.

Part of the reason my father wanted to own a Barn was so that he could experiment with it. Try things out. Like trapezes. Or gardens. Some of his experiments worked brilliantly; some of them, not so much. One of the more interesting ones was a floor treatment, if that’s what you could call it. Dad cut one-inch slices of 2x4s to use as tiles in the front entry room, what we called the tack room (in the days when the Barn was a working barn, it was where various animal-related gear had been stored). It was a good experiment, a sort of prototype. Dad had big plans, see. For the kitchen.

Part of the reason my father wanted to own a Barn was so that he could experiment with it. Try things out. Like trapezes. Or gardens. Some of his experiments worked brilliantly; some of them, not so much. One of the more interesting ones was a floor treatment, if that’s what you could call it. Dad cut one-inch slices of 2x4s to use as tiles in the front entry room, what we called the tack room (in the days when the Barn was a working barn, it was where various animal-related gear had been stored). It was a good experiment, a sort of prototype. Dad had big plans, see. For the kitchen.

I have finally–and reluctantly–joined the vast numbers of my fellow citizens and become part of the COVID statistic. There are many things–good streaming shows or films, books, travel–where I do have a fear of missing out. What if I never get to go to Italy? What if I miss seeing that show with the original cast? What if that restaurant that everyone says is breathtakingly good goes under before I get to try their soup?

I have finally–and reluctantly–joined the vast numbers of my fellow citizens and become part of the COVID statistic. There are many things–good streaming shows or films, books, travel–where I do have a fear of missing out. What if I never get to go to Italy? What if I miss seeing that show with the original cast? What if that restaurant that everyone says is breathtakingly good goes under before I get to try their soup? Some years ago, I struck up a conversation with a young writer at a convention. (I love getting to know other writers, so this is not unusual for me.) One thing led to another, led to lunch, led to getting together on a regular basis, and led to frequently chatting online. I cheered her on as she had her first professional sale and then another, and then a cover story in a prestigious magazine. One of the gifts of such a relationship is not the support I receive from it, but the honor and joy of watching someone else come into her own as an artist, to celebrate her achievements. It’s the opposite of Schadenfreude — it’s taking immense pleasure and pride in the success of someone you have come to care about.

Some years ago, I struck up a conversation with a young writer at a convention. (I love getting to know other writers, so this is not unusual for me.) One thing led to another, led to lunch, led to getting together on a regular basis, and led to frequently chatting online. I cheered her on as she had her first professional sale and then another, and then a cover story in a prestigious magazine. One of the gifts of such a relationship is not the support I receive from it, but the honor and joy of watching someone else come into her own as an artist, to celebrate her achievements. It’s the opposite of Schadenfreude — it’s taking immense pleasure and pride in the success of someone you have come to care about.