2005 was a low point for me: I had lost all my confidence. I was pretty certain that I was a failure in all things intellectual and that I couldn’t write, but I was still very determined to keep going. I stayed with what I loved, even when I was pushed to the side, time after time. People with a single course as an undergraduate ere given work ahead of my PhD in a field, and it hurt.

Everything I wrote that year and into 2006 has underlying rumbles of my lac of confidence. It took me a few more years to discover that the problem had never been with my intellect. Sometimes it was because I am chronically ill (and one is not supposed to be intellectually competent and ill, both), sometimes because I’m not male (such an Australian bias) and, most often, because I’m Jewish. Nice people don’t say antisemitic things… they simply leave Jews out of things, or choose someone ahead of them.

How did my self-image begin to change? When I was at a Melbourne science fiction convention, I was asked to join a panel on Cordwainer Smith. Not by the convention planners, but by the panel itself. I said something and Bruce Gillespie asked me to write it up. This is what I wrote for Bruce:

Cordwainer Smith: reflections on some of his themes

- Canberra and Norstrilia

Canberra in the 1960s was a mere kernel of the Canberra of 2005. It was small and green, mostly buildings and public parkland, surrounded by the enormous brown of rural Australia. This was the Canberra that Corndwainer Smith knew. Not the small internationalist city of today, with its sprawl of suburbs and its café culture, but an overgrown country town that just happened to be the seat of government for a whole country. You can see a sense of this Canberra in Smith’s work, the idea that Norstrilian government is more a set of social compacts than a formal hierarchy, the idea that family and inheritance counts (the earliest settlers in the area still farmed sheep on what are today mere suburbs, Kambah for instance was farmed by the Beattie family) and the ideal that the country is vast and brown and far diminishes the civilisation it nurtures.

There are other reflections of Australian life of the time in Smith’s work. Immigration, for instance.

While policies were much more open than it had been, the inheritance of the White Australia policy was still very apparent in the people of this country. Much of Australia was still white, still Anglo, and still very conservative. In many places, of which Canberra was one, walking down the street one could very easily assume that the only non-Anglos were diplomats, that Australia didn’t let any strangers cross the border unless they had proven their credentials.

This was not the reality. Cordwainer Smith came to Australia at the crucial moment when White Australia was being broken down – indigenous Australians were finally given voting rights, migrants came from places other than the United Kingdom. The effects of this change were not yet apparent, however, outside Melbourne and Sydney and places such as the Queensland canefields. The reality of Canberra in the 1960s was that the hydroelectric scheme and more open immigration policies were bringing more and more people from other parts of Europe into the region – but walking down a Canberra street, the feeling was still very much of the dominant ancestry being British.

The Australia Smith saw was very much the cultural blueprint for Norstilia, with its responsibility towards remembering the British Empire and preserving certain cultural values.

At that time, Australia had a very restrictive economic policy. This included a barrage of tariffs and customs restrictions that have since been phased out. It was openly admitted that these restrictions were to develop the local economy and to protect important elements of it – the Melbourne clothes industry was of particular importance, for instance.

The effect of these import restrictions on everyday life was very marked; Australia was wealthy, but not quite first world. We took a long time to adopt innovations from outside, and luxury goods were particularly highly taxed. At the same time, because food and accommodation were much cheaper than in many other countries and Australian workers worked shorter days, even the poorest person was said to be richer than wealthy people elsewhere, in terms of lifestyle.

Add this to an important religious factor: the default religion people wrote on their census data as Church of England, and the Queen was both head of the Church and head of State. The political crises of the 1970s which disputed and lessened the impact of the royal family had not yet happened, and the most important Prime Minister of the 1960s, Sir Robert Menzies, was a keen royalist. A keen royalist and rather autocratic leader – the exact mix that Cordwainer Smith struggles to describe from a slightly bemused outsider viewpoint in his depiction of Norstrilia.

To the surprised outsider, we could easily have looked like a country that practiced old-fashioned Church of England values. Very High Church – abstemious and full of self-restraint.

Internally, Australia was not really self-restrained. The slow adoption of new technologies such as television were largely because of the distance of Australia from the rest of the world combined with the tariff system. Smith was interpreting this from a High Church view, however, and would be astonished by the current Australia, where abstemiousness and low technology levels are rather absent.

What Smith saw was an Australia ruled by an innocent nobility with power that was mostly inexpressed. This is the source of the apparent abstemiousness as he described it. It showed more in Canberra than elsewhere. There were only two major industries in Canberra at that time: the public service (all national) and the university. Canberra fully understood the outside world, but its lifestyle in no way reflected it. There were secure incomes and workplaces, safe jobs, but not much in the way of luxury. Canberra was a hard place to get to, for a capital city, with only a local airport and only one train station, and it had an extraordinarily suburban lifestyle. It also had (and still has) like Norstrilia an unexpectedly large awareness of the outside world and a sophisticated understanding of how the trade barriers operated.

It is very hard not to see the Canberra of the time in Norstrilia: a place with a sophisticated understanding of the external world, cut off from it and surrounded by bleak but rich countryside dominated by some of the best sheep territory n the world. It is ironic that, well after Paul Linebarger died, Goulburn built its Giant Merino – an enormous grey tribute to the traditional source of wealth in the Canberra region.

- The importance of Abba-dingo

Abba-dingo is particularly important in understanding Cordwainer Smith’s constructed universe. It appears in his short story “Alpha Ralpha Boulevard”. Abba-dingo was a carnival head that took coins or tokens and gave prophecies.

Writers looking for the origins of Smith’s odd names suggest that Abba- comes from the words ‘Abba’ for father from Hebrew or Aramaic, and the Australian native dog, ‘dingo’. While this appeals to me because it calls forth an Australian phrase ‘Old Man Dingo’, I have to admit, that I have large problems with this etymology. I suspect that Abba-dingo comes from a word much closer to home for Paul Linebarger and gives strong indications as to how his religious views shape decision in his universe: it comes from the Book of Daniel.

In the Book of Daniel the king of Babylon visits Jerusalem. He finds several royal Jewish children both beautiful and wise, and he proposes to teach these children the lore of the Chaldeans. He had the children renamed. Azariah was renamed Abednego. Naturally Daniel was the hero of this tale, which is all about true prophecy, but Abednego is linked to the true prophecy and survives his stint in a furnace.

Cordwainer Smith makes the link between Abba-dingo and Abednego quite obvious, as Abednego by using the notion of the fiery furnace and in ‘Alpha ralpha Boulevard” the making the imprint of the prophecy by fire. To make sure we don’t miss the point, in the King James Bible Abednego is always spelled Abed-nego and Smith divides Abba-dingo in the same way.

Abba-dingo then, is a closet reference to the Old Strong Religion. The head is an indication that the universe is planned, even when it looks like a game from a penny arcade. It refers back to the innocents and the holy being able to be given and to live the truth, even when they have no understanding of what is happening.

Cordwainer Smith has devised a predetermined universe based very much on a very High Church reading of the Bible. More than that, he writes a belief in the Select (chosen almost before their birth and with predestined accomplishments) eg D’Joan.

Much of his belief is not modern Church of England at all – it is, to me, very nineteenth century and fundamentalist. This is reflected in the nature of most of his short stories. They are Bunyanesque in feel. He emphasises this feel by the style he uses for the stories where the religion is an important component. He works with carefully built-up introductions and focuses on the inner meaning of lives rather than the individuality and personality of the people involved. This implies that these people are more important for the role they play than as game pieces to catch a reader’s eye.

The track of history and the meaning it all leads to is more important than the tale itself. Each story is, in fact, part of the monumental progress of humankind and animalkinds towards a future that Cordwainer Smith only hints at. Just like Moses, we don’t see Smith’s Holy Land except fro a distance – the voyage to it is more important.

What is important about the Bunyanesque progression is not the end of it. The aim is not to provide a guide to holy living or to a perfect future. Cordwainer Smith is not CS Lewis – his fiction does not preach.

What it provides is a mythical background to his novels. If you read all his short fiction then your read Norstrilia, you have the perfect structure for the assumptions that are made in the novel. He provides a legendary past and important indications of the future. This makes him look extraordinarily innovative, as his stories often use an allegorical or fairytale format rather than one more typical of the SF conventions of his time. Understanding those allegorical and fairytale formats and that legendary past and mythic background are important to understanding how to read the universe he created.

For instance, those indications give us important clues to certain characters (eg C’mell) and enable us to read far more into their behaviour and attribute more to their personalities than would otherwise be possible. Without the background, C’mell looks simply obedient and maybe a bit boring, regardless of her physical beauty, and her reward is the reward of dull virtue. When the reader understands that the Norstrilia section is only a small segment of her life, her reactions take on a much greater complexity.

The skill he brings to his more conventional writing highlights that these departures from convention are quite intentional. Cordwainer Smith was not writing a single novel: he was writing an allegorical universe with a complex history, and he was peopling it with real people (of various species) whose personalities and who capacity to determine their own lives were heavily affected by the allegorical nature of his universe.

Abba-dingo points to this. Cordwainer Smith uses the Abadnego joke to both indicate the religious allegory and to mock at it. Abba-dingo is, after all, only a fairground toy – how do we know that it is God speaking through a fairground mechanical or whether the author is using it as a cheap plot device.

This is the brilliance of Cordwainer Smith. He refers to his Old Strong Religion. He uses his Old Strong Religion. He shapes the whole story of D’Joan and the quest of Chaser O’Neill around a particularly archaic version of Protestant belief. All the traditional allegory and the Biblical and religious knowledge that was commonplace in his youth appears in his writing, from the land of Mizraim (Misr) to the need to forego the quest in order to achieve the true goal.

Yet all the while he uses these patterns, he mocks them. He makes it clear that his is an invented universe. He has his heroes play with space and time like gods, while indicating that they can’t possibly be gods. He creates his Vomact family in such a way that the ambivalence between good and evil is perennially pointed out: we don’t know until we are read a given story whether the Vomact will be hero or villain.

In showing the hand of the creator so very, very clearly, Cordwainer Smith casts doubt on his own allegories. He leaves it to the reader to think it through.

This week I had the joyful and inspiring experience of going in person to hear an interview with Andrea Hairston, who was finishing up a tour in support of her new book, Archangels of Funk.

This week I had the joyful and inspiring experience of going in person to hear an interview with Andrea Hairston, who was finishing up a tour in support of her new book, Archangels of Funk.

Biblio Press, 1988). Posthaste, I ordered a copy of the book and then pored through it. The chapters were short, more summations than in-depth histories. Although quite a few of them piqued my interest, only one suggested a story, that of Dona Gracia Nasi. The section began:

Biblio Press, 1988). Posthaste, I ordered a copy of the book and then pored through it. The chapters were short, more summations than in-depth histories. Although quite a few of them piqued my interest, only one suggested a story, that of Dona Gracia Nasi. The section began:

Twenty odd years ago, when we moved to San Francisco from New York, we bought a house. That flat statement doesn’t reflect the year of living in a rented flat, looking for a house that 1) met our inscrutable criteria for size, price, amenities (this above all: a garage!), proximity to public transport, and some degree of walkability. We were unbelievably fortunate that we sold our NYC apartment for enough to give us a competitive down payment, even in SF (which was then in a wave of utter insanity, real estate-wise). Still, what we wound up with was not one of the gorgeous Victorians with which San Francisco is blessed, but a modest two-bedroom house with a semi-finished attic which would do as a third bedroom, a garage, and a rather feral back yard. Over the years we have made improvements (a workable kitchen which is still my delight; new furnace, new water heater, new bathroom). And this week we started on a massive project: new back yard.

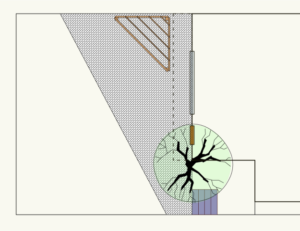

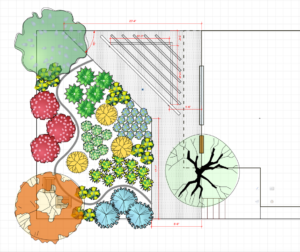

Twenty odd years ago, when we moved to San Francisco from New York, we bought a house. That flat statement doesn’t reflect the year of living in a rented flat, looking for a house that 1) met our inscrutable criteria for size, price, amenities (this above all: a garage!), proximity to public transport, and some degree of walkability. We were unbelievably fortunate that we sold our NYC apartment for enough to give us a competitive down payment, even in SF (which was then in a wave of utter insanity, real estate-wise). Still, what we wound up with was not one of the gorgeous Victorians with which San Francisco is blessed, but a modest two-bedroom house with a semi-finished attic which would do as a third bedroom, a garage, and a rather feral back yard. Over the years we have made improvements (a workable kitchen which is still my delight; new furnace, new water heater, new bathroom). And this week we started on a massive project: new back yard. I have to say, both Danny and I found it hard to really wrap our heads around this as a “here’s what you’ll wind up with” model until we went out back (stepping carefully around the debris) and paced things out. Then we gave the designer some feedback, he made adjustments, and proceeded to send back an image with a rough planting plan thrown in. This time (maybe because there’s some color) I felt more comfortable. There’s a secondary seating area (in the lower left corner) and a “path” among the plantings.

I have to say, both Danny and I found it hard to really wrap our heads around this as a “here’s what you’ll wind up with” model until we went out back (stepping carefully around the debris) and paced things out. Then we gave the designer some feedback, he made adjustments, and proceeded to send back an image with a rough planting plan thrown in. This time (maybe because there’s some color) I felt more comfortable. There’s a secondary seating area (in the lower left corner) and a “path” among the plantings.