Recently, I came across this article on the widespread misconceptions about Vikings.

7 myths about the Vikings that are (almost) totally false

Misconceptions abound about Vikings. They are often depicted as bloodthirsty, unwashed warriors with winged helmets. But that’s a poor picture based largely on Viking portrayals in the 19th century, when they featured in European art either as romantic heroes or exotic savages. The real Vikings, however, were not just the stuff of legend — and they didn’t have wings or horns on their helmets.

This article sparked an online discussion about the myth that all Viking warriors were male. A friend posted:

A myth they didn’t cover is the one that says all the Viking warriors were male. Archaeology is finally recognizing that finding weapons and even a horse skeleton in a grave cannot ensure that the buried person was a man. (It was a myth nurtured by XY archaeologists, convinced they knew it all.)

By sheer coincidence, I saw the article below and mentioned it to my friend. I imagined her grinning as she responded:

Yes – Birka shook everything up in the field, and is making them reevaluate conclusions about a number of earlier excavations.

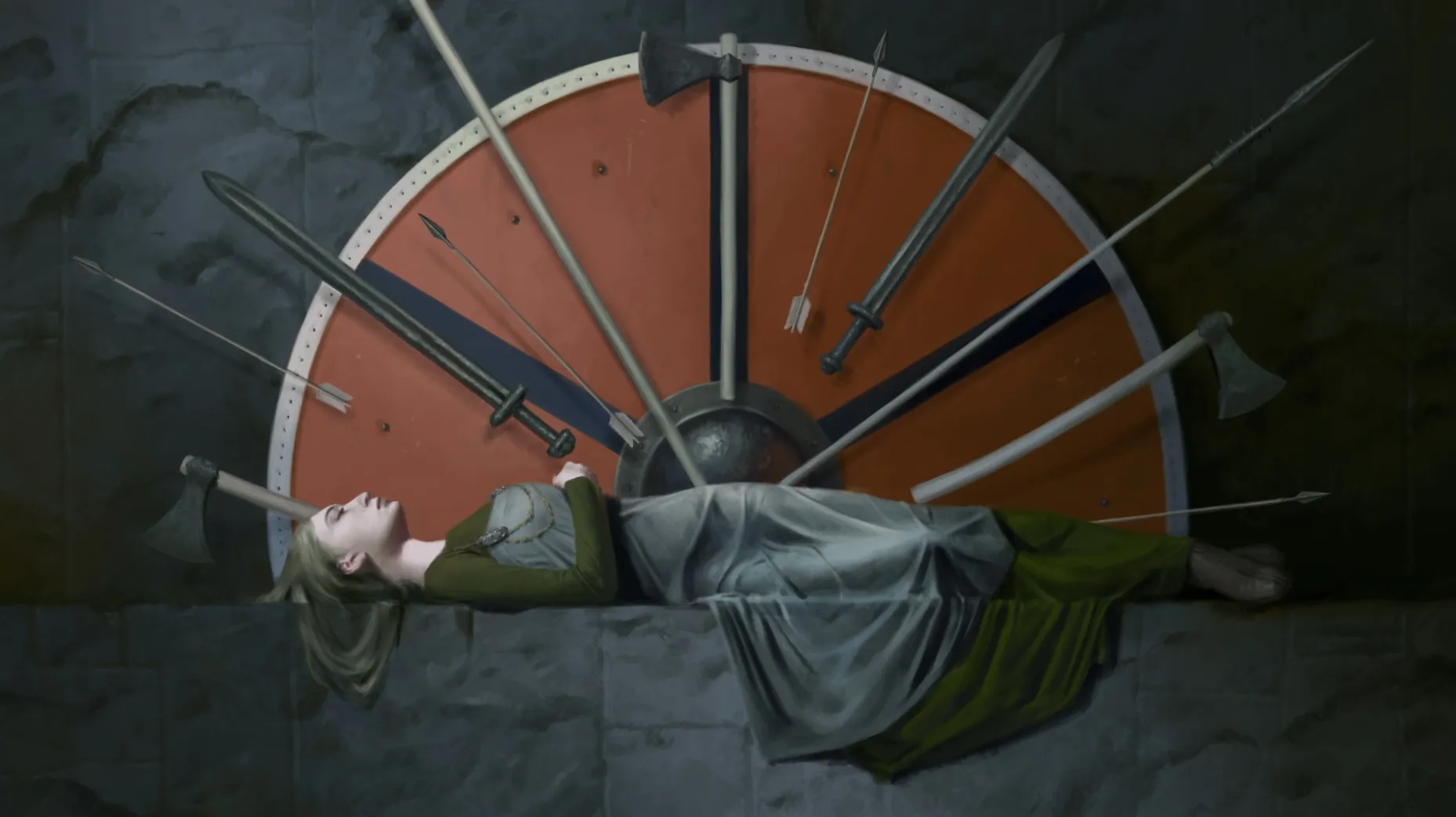

Weapon-filled burials are shaking up what we know about women’s role in Viking society

In Birka, Sweden, there is a roughly 1,000-year-old Viking burial teeming with lethal weapons — a sword, an ax-head, spears, knives, shields and a quiver of arrows — as well as riding equipment and the skeletons of two warhorses. Nearly 150 years ago, when the grave was unearthed, archaeologists assumed they were looking at the burial of a male warrior. But a 2017 DNA analysis of the burial’s skeletal remains revealed the individual was female.

Across Scandinavia, at least a few dozen women from the Viking Age (A.D. 793 to 1066) were buried with war-grade weapons. Collectively, these burials paint a picture that clashes violently with the hypermasculine image of the bearded, burly Viking warrior that has dominated the popular imagination for centuries. And it’s possible that, due to gendered assumptions, archaeologists may be systematically undercounting the number of Viking women buried with weapons.

Archaeologists often guessed the deceased’s sex based on grave goods, such as mirrors, weaving tools and brooches, which archaeologists assumed were typically buried with females, and battle-related weapons, which archaeologists thought were typically buried with males. If a Viking Age sword was the only item recovered, for example, it was nearly always assumed to be a male grave.

Even with that potential bias, there is strong evidence that some women were buried with war-related objects across Scandinavia. Norway has several of what have been nicknamed “shield-maiden” burials, after the women warriors of Scandinavian folklore. One is the Nordre Kjølen burial in Solør, which had a young adult — likely a female, based on a skeletal analysis — interred with a sword, an ax head, a spearhead, arrowheads, a shield boss, a horse skeleton and tools.To put the burials of women with weapons into context, archaeologists have looked at historical texts.

The Vikings left behind only a few thousand runic inscriptions. So most descriptions of warlike women and “shield maidens” come from semihistorical works written during the post-Viking medieval period. For instance, in “Gesta Danorum,” a semifictional history of Denmark by Saxo Grammaticus (who lived circa 1150 to 1220), the warrior woman Lagertha travels with a group of women dressed as men, marries a Viking king who later divorces her, and still fights with him in a pivotal battle.

And some sagas, such as The Saga of Hervör and Heidrek, describe Norse women taking up arms to help protect family property, according to a 1986 analysis. Only men could inherit property, so if a man had only daughters, one was sometimes compelled to step into the role of a warrior as a “functional son” who could protect the family’s interests, according to the study.

The Icelandic sagas, written by people who were likely the Viking’s descendants in the 13th and 14th centuries, include stories about “women leading troops and engaging in acts of violence,” Moen wrote in a 2021 article.

But are these stories evidence that Viking women were warriors in real life? Or did some stories have other mythical or mystical significance? Some evidence points toward the latter. Sagas in which women wield weapons like axes often have magical overtones. In the Old Norse Ljósvetninga saga, for instance, a cross-dressing Norse sorceress strikes the water with an ax to see into the future. Axes are frequently associated with magic in folk traditions from Scandinavia, Finland and Central Europe, Gardeła noted in a 2021 article.

And this:

Hårby Valkyrie: A 1,200-year-old gold Viking Age woman sporting a sword, shield and ponytail

This cast silver figurine of a Valkyrie — a mythological maiden who assists Odin, the Norse god of war — is a unique example of Viking Age metalworking that provides clues about the role of armed women during the time period (793 to 1066).The naturalistic female figure was discovered by metal detectorists in the Danish village of Hårby in 2012 and is currently on display at the National Museum of Denmark.

The tiny female figurine is just 1.3 inches (3.4 centimeters) tall and weighs 0.4 ounces (13.4 grams). Its body is partly hollow, and much of it has been covered with a thin layer of gold. A black metallic alloy called niello has been used to highlight and decorate the object.

The female figurine is depicted with her hair gathered up into a ponytail that cascades down her back. She wears a V-neck dress that ends with a pleated skirt, and a pattern of intricate knots runs around the back and sides. Her left arm is protected by a shield, while her right hand clutches a short double-edged sword.

Because the figure is of an armed woman and likely represents a Valkyrie, Mogens Bo Henriksen, archaeology curator at Museum Odense in Denmark, and Peter Vang Petersen, curator of prehistory at the National Museum of Denmark, wrote in a study of the figurine in the periodical Skalk in 2013.

Valkyries were responsible for choosing which soldiers should die on the battlefield. These assistants to the Norse god of war then accompanied the dead warriors to Valhalla, where they served them plenty of alcohol to tide them over until the end of the world, when Odin needed the dead soldiers’ support to defeat the giants at Ragnarok.

The decorative style of the figurine suggests it was made around A.D. 800, or the early Viking Age. It was found in a field where archaeologists and detectorists discovered other metal objects, including Arab coins, silver ingots and discarded jewelry. Experts think the area may have been a noble’s farm in the Viking Age, complete with a metal craft workshop.

Armed female figures have been found elsewhere in Denmark and in England, but they are typically two-dimensional pendants or brooches. The partly hollow Hårby Valkyrie, however, may have adorned the top of a magical staff, Henriksen and Petersen wrote. According to the Norse sagas, divination women, or völvas, used similar staffs in their rituals. One of the female residents of the farm may once have owned the Hårby Valkyrie and used it as a symbol of power.

But it is also possible that the statue is not a Valkyrie at all but rather a depiction of a real woman. Norse sagas and poems mention that women sometimes took up arms, and the Oseberg Viking ship textiles also depict women carrying swords and holding spears, archaeologist Leszek Gardeła noted in his book “Women and Weapons in the Viking World: Amazons of the North,” (Oxbow Books, 2021). In addition, about 30 Viking Age burials across Scandinavia hold the remains of women who were buried with war-grade weapons, such as swords, spearheads and shields — clues that some elite women from this time may have fought as warriors.

Was reading this article when came out 5 years ago. Got to the picture of a reconstructed face and thought she must be related to Nancy.

Meet Erika the Red: Viking women were warriors too, https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2019/nov/02/viking-woman-warrior-face-reconstruction-national-geographic-documentary