When you have small children you do things with them. At least we did. This is how, 29 years ago, we (including two kindergarteners) wound up in Central Park in New York City, on a June afternoon, waiting for the premiere of the Disney animated film Pocahontas.

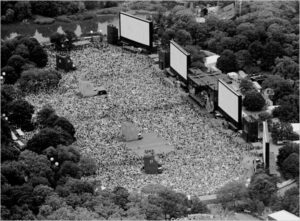

The event was much heralded, and a month or so before the event there was a lottery for tickets. I never win lotteries, but somehow we won this one. We received four tickets, and invited S, one of my daughter’s besties. Came the day, we packed up food and drink and blankets and umbrellas (drizzle threatened for a brief while) and jackets and… all the myriad things you wind up carrying around when you have children. And about 2pm, along with 100,000 of our fellow parents-and-kids, we hied ourselves to Central Park to stake a claim to a bit of ground to call our own among the sea of parents and small children on the Great Lawn. “My God,” my husband said as we were orienting ourselves (four screens! concession stands! phalanxes of port-a-potties! youthful humanity as far as the treeline!) “It’s Kidstock!”

The movie could not start until dark, but this whole thing was being produced (massively, lavishly) by Disney, and if there is one thing that Disney excels at, it is moving people while keeping them just entertained enough that they don’t riot. Especially children. Once we had found ourselves a small holding, one of us (probably my husband) took the girls to reconnoiter. There were various entertainments offered on each of the four stages: singers and appearances by Disney Channel stars and so forth. But mostly our girls chattered and played on our small patch of turf. People we knew passed by on their way to find their own patch of turf. And then the family of A, a boy in the girls’ kindergarten class, came by. We scootched over so they could establish a beachhead adjacent to ours: one of the best tactics of parenting is strength in numbers. It’s much easier to sit on a lawn among 100,000 people if there are four adults watching 3 kids, and you can take turns paying attention.

The day stretched on. Food was consumed. Strolls around to stretch legs and alleviate boredom were taken. A Pocahontas doll was scored for each of the girls. The question “but when will it start” was asked many times. As hard as it is to believe now, this was before smart phones, so instead of a sea of tiny heads bent over screens it was a sea of seething childhood, wiggling and giggling and wishing the sun would set already. And we (Danny and I) began to notice a fascinating bit of kid behavior going on between the three five-year-olds. First, a note about my daughter Jules. She was a dreamy, highly imaginative kid into make-believe and stories. One of the things she did not go in for was the crushes that some kindergarteners indulged in. Her friend S, on the other hand, was the kind of small girl who watched the relationships around her, hawklike, and knew who in the class “liked” whom. S was a pretty girl and used, frankly, to being treated that way; she was always watching the people around her, angling for position. Then there was A, or as his mother referred to him, Mr. Romantic, a sunny, affectionate kid. And Jules was… clueless.

At last the movie starts. The music swells. We settle in to watch. But I kept getting distracted by the little drama that is playing out on our blanket. See, A sort of snuggles up to Jules–whether he meant it romantically or just felt comfortable with her, I don’t know. S, seeing this, sidles over to A’s other side, presenting herself to be snuggled. A does not oblige. S is clearly frustrated by his lack of interest. Meanwhile, Jules is sitting there, eyes on the screen, riveted to the story. Through the 80 minutes of the movie A is watches the movie and occasionally looks at Jules. S watches the movie but is distracted by A’s apparent preference for Jules over herself, and gets antsy and fidgety. Jules is oblivious.

The worst part of the whole experience was, of course, getting packed up and home. The 100,000 people who had arrived over the course of the afternoon now all wanted to be gone and home at the same time. A and his parents said good night and vanished in their own direction. Danny and I packed up our belongings, put jackets on the girls and joined the clog of people heading toward the exits and the West Side. I don’t remember whether we delivered S to her parents or they picked her up from us. I do recall an initial frostiness emanating from S, which I think baffled Jules–suddenly her friend was mad at her, but why? Eventually S was worn down by Jules’s cheery rhapsodies about the movie (“what was your favorite part?”) and her frostiness dissipated. They stayed friends for several years, until time and changes in schools did what the attentions of Mr. Romantic, on a starry New York City night, could not.