I wrote this not-actually-academic piece for my Patreons about a year ago. This is how I play with a concept. It’s what I do in the very early stages of research, when I’m trying to understand what approaches are sensible and which are stupid. I’m giving it to you now, partly because the themes of Hogwarts’ Legacy apply to it and partly because, while I talk about things Jewish in this example, we need to understand embedded prejudice for so many things. I face embedded prejudice every day because of my physical restrictions and because I’m female and Jewish; transpeople are dealing with far too much facing of it right now (and without nearly enough support); and most minority cultures in face it every day (sometimes in horrific ways) while being dealt with by mainstream culture. Australian politics has just demonstrated how poverty brings forward such embedded attitudes, and in the UK ‘class’ shouts as an issue. No country has the same set of biases, but all of us have groups whose everyday is flavoured by how others simply accept stories and what lies embedded in them.

While I’m researching cultural embedding, I’m not on top of this part of the subject yet. That deep acceptance of stereotyping and hate that appears in literature is very difficult.

I really need to focus on more ways of discussing embedded prejudice in my research. I began experiencing how literature delivers wallops related to prejudice when Oliver! (and its source Oliver Twist) caused me many problems as a child, then, when a whole year level studied The Merchant of Venice, I had to deal with it again. The deeper bias in these works are led to by a shallow bias and some really stupid interpretations. Every time Fagin is given a European Jewish accent, for instance, I see the application of the Universal Jew prejudice. Fagin was based upon a real person, Ikey Solomon, who was probably Sephardi and who almost definitely had a London accent. Solomon was well-known for dressing nattily (and for being a high-level, well-connected fence for stolen goods), not for leading children astray. He ended up in Australia (before it was Australia, when it was a bunch of British colonies) and his personal story is so much more fascinating than Dickens’ novel. There’s a modern novel about him, too, but I don’t recommend it because it gets the Jewish side very wrong, too and poses a very different set of problems.

I can’t follow this research up right now – I am in the middle of a project that examines other facets of culture in fiction. This other project is helping me understand how to look at these things fairly. I need that fairness. Not everyone who depicts people using these biases does it intentionally. However, every single one of them hurts people. Since I’m terrified of the impact Hogwarts’ Legacy will have in this respect, I need to share some of my thoughts. These thoughts are neither serious nor complete, but they play with some very important concepts that I will return to, when I can. I’m writing a novel that addresses some of them and I will do old-fashioned research for the rest.

If you want to read something a bit more considered than a daft essay, you will find better discussions (but not of vampires) in my book Story Matrices. I wanted to develop methods that would help writers and editors understand what they’re doing so that they can make active choices in these matters. Story Matrices is that book.

My entirely daft theory about Bram Stoker and his Jewish vampires.

There is one thing you need to know about Bram Stoker, before I can begin talking about his relationship to vampires and my new (totally untenable) daft theory: he didn’t like Jews. If he were brought forward to this century and put on a convention panel with me, he’d be very uncomfortable, even though I don’t match the Jewish stereotypes he carried. I’ve had Thoughts for a while about this, but the Problem of Garlic brought everything together. That’s as good a reason as any to begin with the problem of garlic. Except I can’t.

I’ve been trying to handle this for years. Behind his writing there is something significantly more than the various put-downs you see in other authors of his time and place: he genuinely didn’t like Jews. My current random theory is that this didn’t mean he knew nothing about Jewish culture. He probably didn’t know that he used Jewish culture and also the stuff used to describe Jews by bigots, but his own bias meant that his incorporation of these things together in his work was seamless and convincing and created our classic vampire story. Our classic vampire story, in order words, quietly reinforces antisemitism. Just like Dracula, it looks charming, but it hurts people.

My theory goes (in its wayward way) that he took some Jewish folk culture from Eastern Europe and applied it to vampires. Also, there were quite a few Jews in Transylvania in the nineteenth century. They spoke Hungarian, were classified ethnically as Hungarian, and were citizens. This is the by-product of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. None of them (as far as I can work out) were in any way related to any branch of my family. Jews in Ireland were not granted citizenship until 1846, while most other people were given citizenship in 1783. None of the eighteenth and nineteenth century Irish Jews were in any way related to any branch of my family, either. (This is another aspect of various Jewish cultures – the need to work out relationships to other people.)

And now we’re finally up to that garlic.

There is one very folkish and not at all religious part of Jewish culture that contains garlic as a repellent. Just one. But it’s a big one. In fact, it’s how some Jews handle Christmas.

It’s not been easy to be Jewish over the centuries and much folk culture has sprung up to help people deal with it and the violence towards Jews that can go alongside it. A lot of the folk culture was lost with the various mass murders that tend to be handed out to Jewish populations, but recently, I have been exploring one set of folk practices in particular. This aspect began about 1800 years ago, and it’s the Jewish stories (note the plural) of the life of Jesus. My favourite is, of course, from the Middle Ages and one of several lives of Jesus from that time.

Lives of famous people is such a Medieval thing: it includes the lives of saints, and the spectacular deeds of kings and princes and noble knights. The stories about Jesus don’t fit into those types of stories at all: in this set of Jewish folk cultural traditions Jesus was no saint, king, prince or noble knight. The stories of Jesus all fit into the category of lives about famous magicians, alongside people like Merlin.

All of the versions of the story of Jesus are entirely unacceptable and not-nice from a Christian perspective. My favourite includes flying and the pulling out of hair. Being a polite religion and this being considered fictional and part of folk culture, it was mostly kept hidden from Christians, out of respect. Also, of course, because it isn’t always safe to be Jewish and one doesn’t want to provoke more persecution.

That variant of the life was told on Christmas Eve, for hundreds and hundreds of years. We don’t know which Jewish cultures told it, nor how they did, nor how many knew it, but Christians being upset about the story have written about it over the centuries and scholars have checked what they’ve written against what they knew about Jewish cultural practices and… it really happened. It might still really happen. If it does, it’s not part of my family’s tradition at all.

The stories about Jesus seem to be a way of dealing with antisemitism and its accompanying violence. In far too many times and places it was unsafe to leave the house at Christmas, you see. Stones were thrown at Easter, so Christmas wasn’t the only time and place that it was safer to shut the doors and make home tight and safe and not leave it until the bigotry passed a bit.

This is all related to garlic. I’m getting to that.

When one shuts one’s doors and shutters windows and pretends one isn’t home because otherwise it was dangerous, one develops folkways to keep the evils out. Some European Jews had a tradition, over hundreds of years, of eating garlic on Christmas Eve to keep Jesus away. His rising from the dead, you see, was not interpreted the same way by Jews as by Christians. Garlic, in Eastern Europe from at least the 19th century, kept evil beings away… and while it’s deeply troubling that Jesus was seen as evil by some Jews (historically) when you consider what was done to Jews in his name, it’s very easy to see how this occurred. An undead magician who brought evil with him was kept away by garlic on Christmas Eve. And maybe also salt. I forgot the salt.

Salt has some big baggage. Salt was used in the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth when someone was investigating a case. It was blessed according to Christian rite and put in the mouth of Jewish witnesses to force them to tell the truth. And now I can’t remember if salt was used in Stoker* or in other vampire stories. One day I will check, I promise.

Stoker used folk material from Wallachia and Moldavia for his vampire background. It’s really as simple as that. There was a significant Jewish population (some cultural overlap here with me, because Romania did, at times, include what is now known as Moldova and my mother’s maternal grandparents were from there) and Stoker simply included the whole. His main source was An Account of the Principalities of Wallachia and Moldavia, and was written by the British diplomat in that region, William Wilkinson. Stoker used other sources, but this one is freely available on the web and I can give you a link to it, so it’s the one I’m citing. https://books.google.com.au/books?id=RogMAQAAMAAJ&printsec=frontcover#v=onepage&q&f=false

Really, this is not about Stoker being antisemitic (though he was, and Wilkinson himself describes Jews as of “obscure race” and an “inglorious nation” so he would not have liked me, either) it’s about how cultural practices develop and what happens when an Irish writer doesn’t stop to think about whose culture he’s borrowing and how. It’s about the damage done by inconsidered cultural appropriation.

The vampiric traditions in the various cultures of Europe have little to do with most English vampire stories. My favourite European vampire tradition is that you can handle vampires by strewing seeds and grain on the ground, because they will be forced to collect them and count them and that gives the victim time to escape.

The burial of possible vampires, though, is just as interesting. It has been verified by archaeologists, which is where I found out about bricks. Potential vampires might be buried upside down, or decapitated, or buried with sharp objects to prevent them from doing harm. Some people were buried with bricks in their mouths, to prevent them rising (in Scotland and in Italy as well as in Romania). This is all evidence that European belief in a vampire rising and causing damage is something many cultures share. The vampire as sexy and pale, however, that’s the stuff of novels. (Also, there was a vampire craze in the eighteenth century, and I need to explore this one day. We call all kinds of things vampiric these days, when they were far more clearly demonic possession, and I need to find out where the eighteenth century assigned it.)

The thing is, there was a “Jews are dangerous because they are sexy and pale and lead good Christians astray” cultural construct in the nineteenth century. Also, not everyone considered us full human beings. The impurity of blood notion the Inquisition spread had consequences. And blood drinking is a libel that has been used to attack Jews from the Middle Ages. Invented, and has not a thing to do with either the Jewish religion or any Jewish folkways and debunked so very many times… but Jews are still being accused of it and murdered with it as an excuse and… near-humans who are pale and sexy and find the cross really uncomfortable and drink blood and won’t disappear when you want them gone so you have to resort to violence and awful means? Sounds like vampires to me. The garlic is an extra, a bit of appropriation to make the thing real.

Stoker’s vampire doesn’t fit the folk tradition, but it’s a good literary metaphor for Jews by antisemites. I don’t think it’s that any more, for most people, but the moment I saw the nature of the folkways and bigotry inherent in the first century of vampire tales told to the general public in English (and French, to be honest, and possibly German) I started realising that many of these stories underpin antisemitism and violence.

This is why, when I use vampires, I use them a bit differently. But that’s a different story.

*You need an endnote. Most of what Stoker wrote was borrowed, however, he invented vampires not being visible in mirrors for Dracula. In Judaism, mirrors can be portals for the soul at certain times. I doubt Stoker knew this and I can’t see any evidence of him knowing it, unless he’s describing evidence of vampires not having souls.

Originally published in 2016

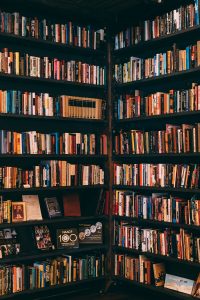

Originally published in 2016 Like almost everyone I know, I have a lot of books. A few fewer since the minor flood in the garage took out a couple of boxes that were stored in anticipation of getting new bookshelves, but generally a lot. For pretty much my entire life, from before I could read, I have believed, somewhere deep in my heart of hearts, that books are a form of wealth. It’s only lately that I realized they were also a form of… insulation? protection? I feel safe when there are books. The more books, the safer. (I have no idea what I need protection from. Boredom? A lack of reading material?)

Like almost everyone I know, I have a lot of books. A few fewer since the minor flood in the garage took out a couple of boxes that were stored in anticipation of getting new bookshelves, but generally a lot. For pretty much my entire life, from before I could read, I have believed, somewhere deep in my heart of hearts, that books are a form of wealth. It’s only lately that I realized they were also a form of… insulation? protection? I feel safe when there are books. The more books, the safer. (I have no idea what I need protection from. Boredom? A lack of reading material?)