What Shakespeare revealed about the chaotic reign of Richard III – and why the play still resonates in the age of Donald Trump

Universal History Archive/Getty Images)

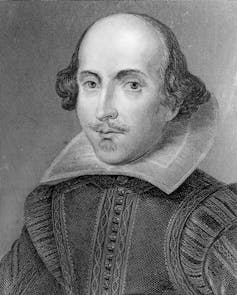

by David Sterling Brown, Trinity College

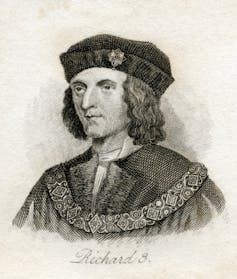

Written around 1592, William Shakespeare’s play “Richard III” follows the reign of England’s infamous monarch and charts the path of a charismatic, cunning figure.

As Shakespeare depicts the king’s reign from June 1483 to August 1485, Richard III’s kingdom was wrought with chaos, confusion and corruption that fueled civil conflict in England.

As a scholar of Shakespeare, I first thought about Richard III and his similarities with Donald Trump after the latter’s debate with President Joe Biden in June 2024. Those similarities – and Shakespeare’s depictions – became even clearer after Trump’s election in November 2024.

Shakespeare’s play highlights the flawed character of a man who wanted to be, in modern terms, a dictator, someone who could do whatever he pleased without any consequences.

In his 1964 essay, “Why I Stopped Hating Shakespeare,” writer James Baldwin concluded that Shakespeare found poetry “in the lives of people” by knowing “that whatever was happening to anyone was happening to him.”

“It is said that Shakespeare’s time was easier than ours, but I doubt it,” Baldwin wrote. “No time can be easy if one is living through it.”

Universal History Archive/Getty Images

A villain?

In Act 2, Scene 3 of Shakespeare’s play, a common citizen says Richard is “full of danger.”

“Woe to the land that’s govern’d by a child,” the citizen further warned.

Beyond hiring murderers to kill his own brother, Shakespeare’s Richard was keen on belittling and distancing himself from people whom he viewed as being not loyal or being in his way – including his wife, Anne.

To clear the way for him to marry his brother’s daughter – his niece Elizabeth – Richard spread what now would be called fake news. In the play, he tells his loyalists “to rumor it abroad that Anne, my wife, is very grievously sick” and “likely to die.”

Richard then poetically reveals her death: “Anne my wife hath bid this world goodnight.”

Yet, before her death, Anne has a sad realization: “Never yet one hour in Richard’s bed / Did I enjoy the golden dew of sleep.”

That sentiment is echoed by Richard’s mother, the Duchess of York, who regrets not strangling “damned” Richard while he was in her “accursed womb.”

As Shakespeare depicts him, Richard III was a self-centered political figure who first appears alone on stage, determined to prove himself a villain.

In Richard’s opening speech, he even says that in order to become king, he will manipulate his own brothers George, the Duke of Clarence, and King Edward IV, “in deadly hate, the one against the other.”

But as his villainous crimes mount up, Richard shares a rare moment of self-awareness: “But I am in / So far in blood that sin will pluck on sin.”

Shakespeare’s Richard III and Trump

While the details of Trump’s and Richard’s lives differ in many ways, there are some similarities.

Much like Trump during his first term, Shakespeare’s Richard did not lead with morals, ethics or integrity.

Richard lied compulsively to everyone, as his soliloquys that contain his innermost thoughts make clear.

Rischgitz/Getty Images

Like Trump, Richard used empty rhetoric to persuade people with “sugared words” – he was not interested in speaking or promoting truth.

Moreover, Shakespeare’s Richard was a sexist and misogynist who verbally and physically disrespected women, including his wife and mother.

In the play, for example, Richard calls Queen Margaret, widow of King Henry VI, a “foul wrinkled witch” and a “hateful withered hag,” thus disparaging her older age.

He refers to Queen Elizabeth, wife of Edward IV, as a “damned strumpet” or prostitute, which she wasn’t.

Additionally, in order to cast doubts on his nephews’ legitimate claims to the throne, Richard spread false rumors about his mother, claiming that she was unfaithful.

AP Photo/Alex Brandon

For his part, Trump has no shortage of disparaging remarks about women. He once called his Democratic presidential rival Hillary Clinton “the devil” and characterized former U.S. House Speaker Nancy Pelosi as “crazy.”

Trump repeatedly peppered Vice President Kamala Harris during the presidential campaign with sexist and racists attacks.

He initially refused to pronounce her name correctly and openly mocked her racial identity as a Black woman, even questioning her “Blackness.”

A new day?

Like Trump, Richard III used religion to manipulate and confuse public perception of his amoral image.

In the play, Richard stages the equivalent of a modern-day photo op, standing between two “churchmen” with a “prayer-book” in his hands.

Much like Richard, Trump has courted evangelicals and used organized religion to his political advantage, most publicly by selling a “God Bless the USA Bible.”

Trump’s 2020 photo op in front of St. John’s Church in Washington is another example. It occurred during protests over the murder of George Floyd, an unarmed Black man killed by a white police officer. Police in riot gear used tear gas to force protesters away from the White House; then Trump was escorted to the nearby church along with several administration officials.

As a political leader, Richard III left a legacy in English history as one of England’s worst monarchs.

That legacy includes his decisive defeat in the Battle of Bosworth Field in 1485 that led to his death and to a new era for England under King Henry VII.

After winning the throne, the new king offered a message of hope that suggested England would one day emerge from its time of civil discord:

Let them not live to taste this land’s increase

That would with treason wound this fair land’s peace!

Now civil wounds are stopped, peace lives again.

That she may long live here, God say amen.

David Sterling Brown, Associate Professor of English, Trinity College

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Continue reading “Shakespeare had a thing or two to say about tyrants”…