Yesterday* was my birthday. The day before that** I turned on the elliptical and programmed it for my workout. Among other intrusive and personal questions*** it asks my age. And I realized, as I pushed the button over and over and over again**** that today was the last time I would enter that particular number. I mean, I could just go on reporting my age as 67–hell, I could have been telling it all along that I was 23–but I think it’s just mean to lie to a robot. They have no sense of humor and cannot defend themselves.

So today***** I am 68. It feels remarkably like 67, or for that matter, like 66. I’m still busy, I’m not as busy as I think I should be, I still like chocolates and baking and the musicals of Stephen Sondheim. I still think Jane Austen is the funniest writer I know. And I’m still wondering when I’m going to grow up.

It seems to me that by and large, people over 21 in my parents’ generation mostly acted their ages******. My parents, who prided themselves on their artistic, slightly off kilter sensibilities, were still grownups. I’m not sure they liked being grownups, but they went ahead and did the grownup thing. My generation may have been the first to celebrate–loudly–its Peter Pan-like disdain for growing up, to the point where it got a little old. But that attitude sticks with me–to quote Mary Martin as Peter Pan, “if growing up means it would be beneath my dignity to climb a tree, I’ll never grow up.”

What Peter doesn’t mention–or doesn’t know about–is the physical limitations of age that may keep me from climbing that tree (I did not break a bone until I was in my 50s, and I would happily not do that again, ever). I don’t do too much tree climbing, but that doesn’t mean I don’t want to. I probably stand on chairs to get things down from high shelves more than a woman of my age ought to do, and I have a friend who scolds me for lifting and carrying things a woman of my age ought not to lift, but that’s part of who I am. I am she who stands on chairs and carries heavy things.

I am privileged in so many ways. I live in a time and place, with history and family behind me, that permits me to retain a grip on frivolity and un-adultness. I will not starve if I am silly. Survival does not rely on my ability to keep my mouth shut, my head down, and plod away in the hopes of staying alive, which has been the lot of generations before me, and is still the lot of too many people around the world. So, in my mostly silly way, I try to help those people in myriad ways, from donating money to writing letters to just being kind to someone who looks like the world is grinding on them a little too hard.

Kindness… there’s a thing. If you wanted to give me a present for my birthday (I’m not saying you should mind you) it would be that. Be kind to everyone you encounter today. Be kind to the people who are grinding through life because that’s all they can do. Be kind to strangers. Be kind to rude people—at dead-least it confuses them, but it may help them find the kindness in themselves. And please, if you will, be kind to yourself. For me, because yesterday******* was my birthday.

_____

* which, at the time I am writing this, is tomorrow

**which will be two days ago when you read this

***like, my weight and which program I want to run

****it’s not a very smart robot–it assumes 40 is the default age, and you have to add or subtract years one at a time until you reach your age

*****which, as you may remember, is actually two days from when I’m writing this

******although the cocktail-culture of my parents’ generation may have been their way of cutting loose of grownup-hood for an evening or six

******* which is actually tomorrow as I write this

Shortly after dawn most mornings, a crow calls loudly, “Caw, caw, caw, caw.” It seems to be speaking to the whole neighborhood of crows, though I’m not sure how large an area this announcement covers. I refer to this as the “Call to Prayer,” because it reminds me of the calls used by mosques, but I don’t know its true purpose.

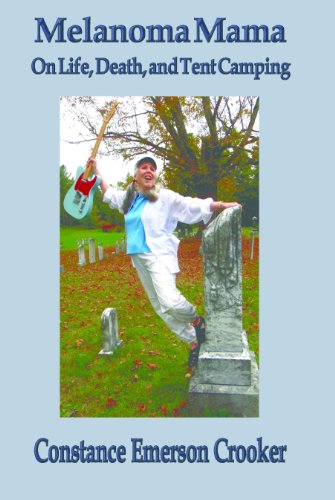

Shortly after dawn most mornings, a crow calls loudly, “Caw, caw, caw, caw.” It seems to be speaking to the whole neighborhood of crows, though I’m not sure how large an area this announcement covers. I refer to this as the “Call to Prayer,” because it reminds me of the calls used by mosques, but I don’t know its true purpose. One of the things Connie did was to go tent camping across America. Another thing was to write about it and her cancer. I slowly read and savored her memoir,

One of the things Connie did was to go tent camping across America. Another thing was to write about it and her cancer. I slowly read and savored her memoir,