I was raised informally; the teachers at my (progressive) grade school were addressed by there first names; I called my parents’ friends by the first names as well–no Aunt or Uncle unless they insisted (only one person–my father’s accountant’s wife–insisted). This doesn’t mean I didn’t treat them respectfully, but it does mean that I grew up expecting a certain amount of reciprocal respect. When we moved and I went to a more traditional school, I called the teachers Miss/Mrs/Mr. I did ask once why we didn’t call all the female teachers Ms, and was told without irony it was because they didn’t have that many young unmarried women on staff. Okay then.

I was raised informally; the teachers at my (progressive) grade school were addressed by there first names; I called my parents’ friends by the first names as well–no Aunt or Uncle unless they insisted (only one person–my father’s accountant’s wife–insisted). This doesn’t mean I didn’t treat them respectfully, but it does mean that I grew up expecting a certain amount of reciprocal respect. When we moved and I went to a more traditional school, I called the teachers Miss/Mrs/Mr. I did ask once why we didn’t call all the female teachers Ms, and was told without irony it was because they didn’t have that many young unmarried women on staff. Okay then.

I believe people should be called what they want to be called (within reason: if you want to be styled Grand Panjandrum, okay, but don’t expect me to do it without an eyeroll). And until invited to do otherwise I still call doctors “Doctor,” regardless of whether they are MDs, DDS, PhDs, or any of the other long list of doctorate degrees. My father-in-law had a doctorate in Education, and while he didn’t do it often, he occasionally would insist on being “Doctor Caccavo.” Because he By God worked for that degree, and the prerequisite degrees, all while supporting a family.

For what it’s worth, in the UK, up until very recently, some medical doctors were Dr. and some were Miss or Mrs. or Mr. Allow me to put my Medical History Geek Glasses on: in the Middle Ages there were three classes of medical practitioners: doctors, surgeons, and apothecaries. Doctors were the ones who had studied medicine; they’d gone to school and learned all the theories. They did not lay hands upon the patient except in the most basic way–that was for assistants, or for surgeons. Surgeons were tradesmen: they used their hands, they apprenticed, learned the skills required, and practiced (some cut hair and pulled teeth as well; Sweeney Todd may have been a Demon barber, but he was also expected to be a dentist as well). Even up to the beginning of the 21st century, aspiring surgeons were plain Mister or Ms. until they finished medical school–then were briefly Doctors, until they finished surgical training and passed their exams, at which point they returned to Mister/Ms. again.

Don’t get your knickers in a twist about doctor. When I hear people deriding Jill Biden because she’s only a PhD I want to send the ghost of my father-in-law to explain to them at length what it takes to get a doctorate.

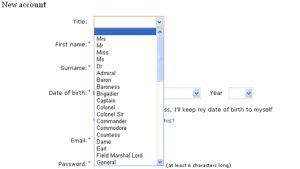

When I started working the rule was: when you met someone you began with “Mr/Miss/Mrs” and took cues as to when it was appropriate to start “tutoyering” the person you were talking to (in French, tutoyer is to use the familiar second person singular “tu” with someone). I don’t always want to start out with the verbal assumption that we’re best buds: sometimes there a power dynamic involved: if I’m calling the person I’m dealing with Mr. Smith and he’s calling me Madeleine, he’s implying something about who is more important. At which point I either request to be Ms. Robins, or start calling him Sid. Things can get tetchy. In certain transactions being addressed by my first name is only one step up from being called “Honey,” and is guaranteed to make me see big red stars. The informality which was meant to make the world a friendlier place can become the source of anxiety and even hostility.

The formality ship appears to have sailed. Every email I get addresses me by my first name (although the writer signs herself with her first name, so there’s that). Platforms that I use for work (I’m thinking specifically of Peerspace, a space-rental platform through which people can find/rent space in the museum where I work) lists everyone by their first name and last initial. I think Peerspace does this as a way of preserving privacy AND keeping guests and hosts from connecting off-platform and cutting them out of the transaction, but the “Hi, let’s be best friends!” tone lingers.

We’re all calling each other by our first names. It’s nice. It’s casual. And I have no problem with that, as long as both of us remember that we’re here to do business–whether it’s getting medical advice or renting a space or vetting a contract. But I’m also willing to go back to the formality of honorifics, if it means that we will all be taken seriously.

I grew up in a small town founded by Quakers. They were conservative Quakers affiliated with the Wichita (Kansas) Annual meeting, but they did hold to a Quaker tradition of calling everyone by their first names. This may have been partly because a large number of people in the town shared the last name of Brown. Cecil Brown Sr., the patriarch of the community, was always Mr. Cecil, and in school we did call all the teachers Mr. or Miss or Mrs. whatever.

My brother-in-law, who taught high school physics for many years, got a doctorate in science education. (He was extremely good at teaching a very complicated subject and had spent a lot of time figuring out how to do it. He was even honored at the White House as a teacher of the year.) I gather that he was often referred to as “Doc” by his students. I find this to be a nice way of combining recognition of his work with some informality.

I tend to the informal myself, but back when I practiced law and had African American clients older than myself, I always addressed them as Mr. or Mrs. because I knew all too well that they had been called by their first names by people they called Mr. or Mrs. I always figure erring on the side of formality isn’t a bad plan.

You can always step down from formality–“Your Mother was Mrs. Smith? Funny, mine was Mrs. Robins. Call me Madeleine.” Stepping up from informality is usually…awkward.