I’m still dreaming about fairytales.

Today’s dream is strongly influenced by a book that’s been on my coffee table for a while. It’s on my coffee table to remind me about certain constructs it discusses. Until I finish thinking through these constructs, it will stay there. It’s been on my coffee table for two months now, because that’s how much is in it that helps me think things through. What is this mysterious book? It’s White Christian Privilege and it’s by Khyati Y. Joshi. https://bookshop.org/a/1838/9781479840236

It reminds me (and is a very good introduction to the understanding of) what it means to be from a majority culture background (or not) in the US. I’m not from that background, so it also helps me see how and why I am who I am and have certain in experiences in relation to those who are from that background.

None of this is why I’m thinking about the book today. First off, I’m thinking about the normative nature of American White Christian Privilege in the publishing world, along with that linked (and older) standard White British Privilege. And today, just ‘cos, I’m not thinking about how the White Australia policy’s legacy in Australia mean I’ll never be quite White, or Christian, or American. All these things have had some large ramifications for my life so far, and no doubt will continue to do so but… today I’m thinking about its influence on how we see fairy tales, or, more precisely, fairy tale retellings.

Fairy tales have always been explained using European views. This goes back to the beginning of fairy tale analysis. Folk motifs and tale types revolve around European culture. This cultural heartland for fairy tales has been mostly carried over into US scholarship. Fairy tales are defined by Europe and retold in cultures where we need to factor in White American privilege.

This means that some tellers are valued more than others – it helps a writing career to have privilege. American writers are more heard than Indonesian writers or writers from Eswatini. There is a hierarchy of countries in publishing, where one is in relation to those privileges makes most of us invisible and unless one is visible. A few extraordinary writers are visible regardless. Rabindranath Tagore and Stanisław Lem and Tove Jansson are good examples of this. Despite the Tove Janssons of this world, there are core cultures that are more visible, secondary cultures (like Australian) that are rather difficult but not at all impossible, and then there are writers from most of the countries of the world who, even in English translation, are not visible. How many of us have read Pramoedya Ananta Toer’s work, for instance. Not me… yet – I need to get hold of it and read it. Every year I spend some time identifying amazing writers I haven’t yet read because they’re not buffered by much of that privilege. I keep discovering many great works and brilliant writers and my life is forever enriched but… none of this is what I’m thinking about today.

Today I’m thinking about how we define certain types of story as fairy tale and we (scholars in the field) generally don’t automatically think “Why is this story classified with these other stories?” It’s culturally problematic to define all story types from around the world in a certain way. It’s great for many reasons (seeing who uses what kind of tale, finding out how stories spread) but it operates in the same way as that White Christian Privilege.

Joshi spends a lot of time explaining that this privilege is not a layer of opportunity and gloss on top of everyday life: it’s the fabric of everyday life. Equally, getting rid of the cultural context for, say, a story taken from the Talmud, or something from the Dreamtime, and reducing it to common denominators, is putting the cultural interpretation of mostly-White, mostly-Western scholars and fiction writers above most of those who tell and use the stories.

They may be fairy tales, and seen as fairy tales, but what if they aren’t? What if they’re part of an immense and complex songlines that cross a whole continent and that predate our knowledge of the fairy tale by thousands of years (at least) and tens of thousands of years?

My questions include the critical one: what do we do to stories when we strip away all of this meaning from them? My answer is that we lose how they’re told, why they’re told, who has cultural responsibility to tell and interpret them and we lose the capacity to see why and how this responsibility is important for the story itself. So many Jews are taught how to read Talmud. We can take stories apparently out of context, and give them relevant contexts in the retelling – this is a part of the upbringing of many of us but… in a world of White Chrsitian Privilege, it’s more likely that someone (even someone Jewish, who lacks this specific training) will see those stories as fair game for retelling from a White Christian perspective. The story derived from this approach will sell better than something with the original contexts still attached, but its culture of origin will be compromised.

There are many ways of handling this.

One is to maintain the commonalities (especially theose that allow the story to be included in those scholarly indices that bring the world of folk tale and folk motif together) but to make sure, as scholars, that the cultural base of all tales are understood. Stories from pre-colonial Australia would, then, always have notes saying where the story was collected, which songline/s it belongs to, and whether the story has been reinterpreted to meet international tale and motif expectations.

Another approach is to read more books by people who come from different backgrounds, and to look for books that address cultural issues as part of the storytelling. My current coffee table book for this is This all Come Back Now (ed Mykaela Saunders) https://blackwells.co.uk/bookshop/product/This-All-Come-Back-Now-by-Mykaela-Saunders/9780702265662 .I was happy to give a story for the Other Covenants volume, sharing my rather peculiar background (ed Lobel and Shainblum) https://bookshop.org/a/1838/9781953829405. Some of the stories fit within a general normative context (not all, but enough to make it readable) but both volumes as a whole question all contexts and present more varied cultural background.

There are other approaches, but two are enough for one day. It boils down to knowing where we (as readers) fit in relation to various types of cultural privilege and for us (again, as readers) to reach out beyond that and to read work by writers who come from a range of backgrounds. Our reading is richer and our life is more interesting.

Also, and this is my favourite side effect from questioning privilege, when we ask about how we interpret fairy tales and looking at what stories have been drawn into that net that are not actually fairy tales, doors open to enormous numbers of brilliant writers. Many haven’t yet been translated into English, but the more we read beyond our tiny cultural boundaries and the more we question our privileges, the more publishers will say “That sold well. Let me try another translation of a famous writer from this background.” The more we work on living in a bigger world, the more that bigger world has to offer us.

Part of the reason my father wanted to own a Barn was so that he could experiment with it. Try things out. Like trapezes. Or gardens. Some of his experiments worked brilliantly; some of them, not so much. One of the more interesting ones was a floor treatment, if that’s what you could call it. Dad cut one-inch slices of 2x4s to use as tiles in the front entry room, what we called the tack room (in the days when the Barn was a working barn, it was where various animal-related gear had been stored). It was a good experiment, a sort of prototype. Dad had big plans, see. For the kitchen.

Part of the reason my father wanted to own a Barn was so that he could experiment with it. Try things out. Like trapezes. Or gardens. Some of his experiments worked brilliantly; some of them, not so much. One of the more interesting ones was a floor treatment, if that’s what you could call it. Dad cut one-inch slices of 2x4s to use as tiles in the front entry room, what we called the tack room (in the days when the Barn was a working barn, it was where various animal-related gear had been stored). It was a good experiment, a sort of prototype. Dad had big plans, see. For the kitchen.

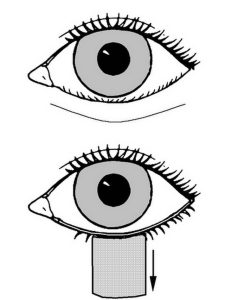

I’m weirdly fascinated by medical neep. This goes back, probably, to having my tonsils out when I was 5 (I was so excited that I fought off the pre-op sedative, to the point where they had to take me down to surgery and pipe ether into me, because I wanted to see everything that was happening). I discovered medical non-fiction–the terrific “Annals of Medicine” series by New Yorker essayist

I’m weirdly fascinated by medical neep. This goes back, probably, to having my tonsils out when I was 5 (I was so excited that I fought off the pre-op sedative, to the point where they had to take me down to surgery and pipe ether into me, because I wanted to see everything that was happening). I discovered medical non-fiction–the terrific “Annals of Medicine” series by New Yorker essayist

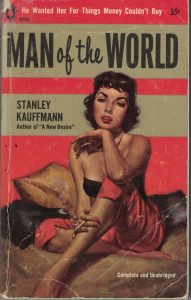

In the annals of 1950s cheesy paperback covers, surely Man of the World should feature somewhere. The sell line (“He wanted her for things money couldn’t buy”) drips innuendo, without actually saying anything. The babe on the cover is sultry. The promise that it’s “complete and unabridged” suggests that there are naughty bits that a more timid publisher might have expurgated. I found nothing that by current standards would be considered naughty.

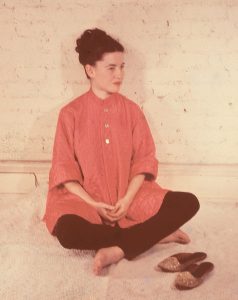

In the annals of 1950s cheesy paperback covers, surely Man of the World should feature somewhere. The sell line (“He wanted her for things money couldn’t buy”) drips innuendo, without actually saying anything. The babe on the cover is sultry. The promise that it’s “complete and unabridged” suggests that there are naughty bits that a more timid publisher might have expurgated. I found nothing that by current standards would be considered naughty. When my parents met my father was married to a woman named Kit, who was a model, Vogue Magazine beautiful, and apparently a… difficult person. According to the novel, the protagonists (Nick and Delia) have a rather chaste thing going on–she lives with her mother, as my mother did–and they go to the movies or out to dinner. Early on in the book she decides this is going nowhere, and moves to New York. Okay, so far it jibes with family lore. My mother moved to New York and lived in a walk-up over a men’s haberdashery across 6th Avenue from the Women’s House of Detention on 9th Street. My father moved back to New York, having split with the beautiful Kit. He had an apartment-and-studio on 11th Street. Somehow they got back together.

When my parents met my father was married to a woman named Kit, who was a model, Vogue Magazine beautiful, and apparently a… difficult person. According to the novel, the protagonists (Nick and Delia) have a rather chaste thing going on–she lives with her mother, as my mother did–and they go to the movies or out to dinner. Early on in the book she decides this is going nowhere, and moves to New York. Okay, so far it jibes with family lore. My mother moved to New York and lived in a walk-up over a men’s haberdashery across 6th Avenue from the Women’s House of Detention on 9th Street. My father moved back to New York, having split with the beautiful Kit. He had an apartment-and-studio on 11th Street. Somehow they got back together.