So many posts and thoughts online talk about 2025 and what happened and what a good year it was. So many of my friends have written me cheerful season’s greetings saying “Happy Chanukah” after Chanukah is over (this happens every year) and hoping I had a really good Chanukah and… I’m Jewish, so of course I get these greetings and these thoughts. I’m Australian and it’s a hot summer and most people are very cheerful. I’m Jewish Australian and every single friend who sends me happy notes and telling me I am enjoying the season is ignoring the elephant in the room: antisemitism.

I only knew one person who was killed at Bondi. I know many people who were on that beach, however. I have family who live in Bondi. No-one expected me to be cheerful during the summer holidays that followed the massacre in Israel. Yet this year they stick to happy thoughts and tell me Chanukah is a time of cheer.

What is happening here?

First, Jewish pain in Australia doesn’t count for much, and Jewish problems in Australia are often pushed to the side. This is how Australia reached the events of December 14. The police are more willing to send officers to monitor protests than to send officers for a Jewish beach party when there are known threats against the party. While most Australians disagree with this, there are far too many who have said publicly these last two weeks that Jewish events should not take place in public and that Jews should handle every bit of risk ourselves.

This is familiar turf for bigots of most kinds. It’s pretty standard where there is race bigotry, class bigotry, bigotry due to skin colour, against new immigrants. It’s pretty nasty, whoever is told “It’s your fault, keep us out of it.” School bullies win when the class president says “Sort it out yourself.”

When the non-violent equivalent happened to me in the public service, I lost my career. “You can sort it out between yourselves,” my branch head told me. I couldn’t. Also, it took me far too long to realise that the work community that pranked me and left me out of things because I’m Jewish was part of a wider community that kept telling me that English was not my native language, and that both these things are part of a bigger picture that paints Jews as different and not people to support. Not all Australians… but enough Australians so that one of my friends went to twelve funerals in a week. And back then, we dealt with Molotov cocktails, not guns. Back then, no-one was hurt.

There is a wider context for this.

Jewish Australians have been around since 1788. One of the very first free settlers in Australia was Jewish. Her name was Roseanna or Rosanna. Her mother was Esther Abrahams, who was a very young convict. I am part of a colonialist-settler society and am one of the settlers. That country is Australia. Indigenous Australians are still fighting for equality and safety.

When I compare what happens on a daily basis to my Indigenous Australian friends and myself and my Jewish friends in the present (after the attempts by at genocide and ethnic cleansing in colonial Australia), it strikes me that an important difference between us historically is that Jews can ‘pass.’ This is why public Jewish events are so wrong for some: Jews don’t try to pass and are guilty of being visible. We’re seen. In public. As Jews. That’s why synagogues and Jewish schools and cars that announce “Happy Chanukah” have been targeted recently. Chanukah by the Beach was publicly Jewish. If we went into hiding, I’m told, we’d be fine.

Australia is developing new cultural structures and the prejudices and hate show what those structures are. Too many politicians (especially on the Left) and far, far too many people at the glittering end of the Arts are passive bigots. They are led by active bigots. Those active bigots spoke up loudly and publicly against the shooting, but almost none of them got in touch with Jewish colleagues to check we were OK. I say this as one of their Jewish colleagues. None of the Greens I know and only a small number of my writer and artist friends got in touch with me. Other Australians did. Non-Australian friends did.

Every friend who contacted me is a treasure. Everyone who did not, has made it clear who they are. In some circles, there’s public virtue but not private.

This is shaping Australia: some writers can have books in bookshops, some artists can get grants. Too much Jewishness or the wrong kind of Jewishness and you are, regretfully, pushed to the end of a queue. I’ve been told I’m privileged and White and should step aside and let others who have suffered discrimination take my place in this event or that conversation. This has been going on for about 15 years. More historical context.

It’s not obvious hatred. These people are otherwise good and charming and often witty. They just don’t want Jew cooties and, in the not wanting, create new layers to Australian society to protect themselves from said Jew cooties. It’s fine to have a Jewish friend, but you should not engage in private conversation with them when bad things happen. If a Jew is banned from certain circles, you don’t protest it.

Most Jews are currently lesser beings and our company can contaminate. We aren’t the only ones, but I experience the Jewish side every day, so the antisemitism is something I can talk about. I speak from personal experience.

It began, years ago, with Jewish writers and historians having to be the Ginger Rogers in our society. We had to do everything everyone else did, but better, on subjects others approved of, as if we were dancing backwards and in heels.

This Gentlemen’s Agreement approach to Jewish Australians has been around since Federation. And earlier, but Federation and the infamous White Australia Policy contain clear issues that apply today. Under White Australia, only special Jews were White. Sir Isaac Isaacs, the first Australian Governor-General, was Honorary White. Sir John Monash, who was rather important in World War I… was not. The official war correspondent (Mr Bean) did all he could to make sure Monash didn’t get the job. Even today, military and ex-military will (for the most part) treat Jewish Australians like any other Australian, due to Monash. But my electorate was named after Bean, and the far left and the far right now both shout that Jews need to be deported. The left is too busy hating Israel to come to the aid of Jewish Australians, and I am mostly banned from conversations with politically active old friends and colleagues because I don’t pass their purity tests. (I don’t pass because I refuse to do them, to be fair.)

These Australians are not even close to the whole of Australia. This is a limited number of Australians in a limited number of power blocks. If they weren’t building on the old hates that led – in Germany – to Holocaust, I wouldn’t be so worried. If Chanukah by the Beach had not been one of the worst mass murders in this country in the last fifty years, I would not be so worried.

While I can see where the passive bigotry is leading, it would take 10,000 words to explain. How about just two observations?

The first, is that it’s like frogs in a saucepan. The Left and the Literati and the politicians presenting that passive bigotry are enjoying a bath in the saucepan and we’re telling them the fire has been lit underneath it. Because we’re Jewish, some tell us “You’re the boy who cried wolf” and ignore what we say. These folks also ignored our concerns right up to the moment the shooters started to fire at Bondi.

The second is, if you factor in the history of antisemitism DownUnder, and if you add the history of treatment of others who’ve dealt with bigotry, right now, it looks like we’re heading for a society structured by bigotry.

This is canary in coalmine stuff. Every time antisemitism is rampant here, historically, we develop concerns about people from this background or that: non-English speakers, recent migrants, those from other religions, women. Indigenous Australians have never been let off that particular hook, and the Indigenous Australians I know and who I listen to are divided between those who support Jew-hate and those who fight alongside the Jewish community. I’m pretty sure (since I know some of the hate-supporters) that they have no idea they are antisemites. At least three I know believe they’re supporting people on the other side of the world by putting us in our place.

Some bigots think they’re doing the right thing. So did the guys who designed White Australia, which is the last time we had a divide this big and this dangerous (skipping World War II, because I am reaching my limits on the subject of hate, and these last few weeks have reminded me of how my European family disappeared). World War I and all the Australian soldiers (especially those who came from the various demeaned groups) broke that to pieces. World War I didn’t get rid of it, though. The social structure still hurt Indigenous Australians in appalling ways… and that aspect didn’t even begin to be addressed until the 1960s. It still hurts far too many.

One of the reasons the antisemitism brings down the whole of Australia: it’s never been only about Jew cooties.

Many Australians have always fought the hate and the fear and the cooties. Some Indigenous Australians are so much more capable than I am, and work for their own communities and for others who hurt. One of my heroes is William Cooper, a Yorta Yorta elder, who, when he and his family and friends were all not-quite-citizens marched to the German consulate in Melbourne after Kristallnacht and let Germany know what they were doing to their Jews was evil.

If you read his biography, you get a sense of what he had to handle in an almost-impossible everyday and how extraordinary he was… and why it’s so problematic that Australia is returning to this particular outlook.

I see so many otherwise intelligent people saying “The shooting was over two weeks ago – let’s spend the next 20 minutes on another crisis” when this crisis is linked to the other they then describe. I hear others saying “It’s the Jews’ fault,” and yet others explaining, “Jews are liars and shot themselves at Bondi. Look to Mossad.” There is passive hate, active hate, aggressive hate – every single bit of hate that’s shared, adds to the Jew cooties and changes the country.

This is why I couldn’t post last week. Getting through this is a full-time job because we don’t have enough words for it because those who have words are part of the problem. It’s a very Australian antisemitism. Like Australian Christmasses, it happens upside down to the rest of the world and is connected to the lives of so many people on our continent. I’m scared for myself and my family and my Jewish friends, but I’m also worried for Australia. My metaphors are still inept, but when a society changes this much it’s really, really bad.

It was as I was making the cake that I realized I do have some very favorite kitchen tools: my instant-read thermometer, my kitchen scale, my decorating turntable, and my cake lifter. The utility of the instant-read thermometer is pretty obvious: no matter if you’re making fudge or rib roast, being able to know what the temperature of the object is can be crucial. When I bake bread I can be misled as to the doneness by the golden color of the loaf, but my instant-read thermometer will tell me the truth about the interior. If I’m making filling for a cake, the instant read thermometer will keep me from turning the it into something stodgy and unlovely. I use my instant read thermometer daily.

It was as I was making the cake that I realized I do have some very favorite kitchen tools: my instant-read thermometer, my kitchen scale, my decorating turntable, and my cake lifter. The utility of the instant-read thermometer is pretty obvious: no matter if you’re making fudge or rib roast, being able to know what the temperature of the object is can be crucial. When I bake bread I can be misled as to the doneness by the golden color of the loaf, but my instant-read thermometer will tell me the truth about the interior. If I’m making filling for a cake, the instant read thermometer will keep me from turning the it into something stodgy and unlovely. I use my instant read thermometer daily.

I am re-reading a book that was published in 1969 (Rumer Godden’s In This House of Brede*). As I was enjoying the things that go along with a re-read (the comfort of a known plot which allows you to sink into the characters, renewed enjoyment of the writing, discoveries of things you slid past on the first readings) I realized that I was also reminded of the way the books of my youth were made, which is different from the way they are generally made today. Lemme ‘splain.

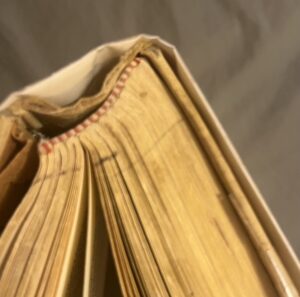

I am re-reading a book that was published in 1969 (Rumer Godden’s In This House of Brede*). As I was enjoying the things that go along with a re-read (the comfort of a known plot which allows you to sink into the characters, renewed enjoyment of the writing, discoveries of things you slid past on the first readings) I realized that I was also reminded of the way the books of my youth were made, which is different from the way they are generally made today. Lemme ‘splain. Until the advent of paperbacks, books (almost all, at least in the Western world) were sewn. In the photo on the right you can see the stitches at about 1″ intervals. (

Until the advent of paperbacks, books (almost all, at least in the Western world) were sewn. In the photo on the right you can see the stitches at about 1″ intervals. (