What would you do if you found out that someone had stolen your idea for writing a book and published it under their name?

First of all, ideas can’t be copyrighted, but I must add—with emphasis—that there are vanishingly few original ideas. What makes a book uniquely yours is what you do with that idea. The vision and skill in execution that make it personal.

So what would I do? I’d cheer them on for having a great idea and for having gotten it in print. And then I’d write my own interpretation.

The best short story rejection I ever received was from a prestigious anthology. The editor loved my story but had just bought one on the same theme (mothers and cephalopods, although mine was with octopodes and the other with squid)—get this, from one of my dearest friends, a magnificent writer. Did I sulk? Did I mope? No, I celebrated her sale along with her! And then sold my story to another market.

In other words, be generous. If you do your work as a writer, this won’t be the only great idea you get.

How can you tell if a book needs an editor or a proofreader?

It does. Trust me on this. It doesn’t matter how brilliant the story is or how many books you’ve written. None of us can see our own flaws, whether they are grammar and typos or inconsistent, flat characters or plot holes you could drive a Sherman tank through. Or unintentionally offensive racial/sexist/ableist/etc. language. Every writer, for every project, needs that second pair of skilled, thoughtful eyes on the manuscript.

How do I get a self-published book into libraries?

If your book is available in print, the best way is to use IngramSpark and pay for an ad. Libraries are very reluctant to order KDP (Amazon) print editions. Same for bookstores.

If your book is digital only, put it out through Draft2Digital (D2D), which distributes to many vendors, including a number that sell to libraries.

Submit review copies to Library Journal. Consider paying for an ad if your budget allows.

Now for the hard part: publicizing your book to libraries. Besides contacting local libraries, assemble a list of contact emails for purchasing librarians (there may be such a thing already, so do a web search). Write a dynamite pitch. Send out emails with ordering links.

Is it better to title my chapters, or should I just stick to numbering them?

There is no “better.” There are conventions that change with time. Do what you love. Just as titles vs numbers cannot sell a book, neither will they sink a sale. If your editor or publisher has a house style, they’ll tell you and then you can argue with them.

That said, as a reader I love chapter titles. As an author, I sometimes come up with brilliant titles but I haven’t managed to do so for an entire novel, so I default to numbers. One of these years, I’ll ditch consistency and mix and match them. Won’t that be fun!

Part of the reason my father wanted to own a Barn was so that he could experiment with it. Try things out. Like trapezes. Or gardens. Some of his experiments worked brilliantly; some of them, not so much. One of the more interesting ones was a floor treatment, if that’s what you could call it. Dad cut one-inch slices of 2x4s to use as tiles in the front entry room, what we called the tack room (in the days when the Barn was a working barn, it was where various animal-related gear had been stored). It was a good experiment, a sort of prototype. Dad had big plans, see. For the kitchen.

Part of the reason my father wanted to own a Barn was so that he could experiment with it. Try things out. Like trapezes. Or gardens. Some of his experiments worked brilliantly; some of them, not so much. One of the more interesting ones was a floor treatment, if that’s what you could call it. Dad cut one-inch slices of 2x4s to use as tiles in the front entry room, what we called the tack room (in the days when the Barn was a working barn, it was where various animal-related gear had been stored). It was a good experiment, a sort of prototype. Dad had big plans, see. For the kitchen.

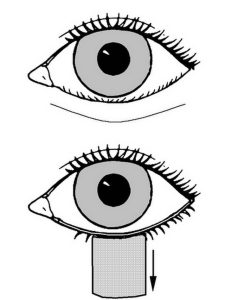

I’m weirdly fascinated by medical neep. This goes back, probably, to having my tonsils out when I was 5 (I was so excited that I fought off the pre-op sedative, to the point where they had to take me down to surgery and pipe ether into me, because I wanted to see everything that was happening). I discovered medical non-fiction–the terrific “Annals of Medicine” series by New Yorker essayist

I’m weirdly fascinated by medical neep. This goes back, probably, to having my tonsils out when I was 5 (I was so excited that I fought off the pre-op sedative, to the point where they had to take me down to surgery and pipe ether into me, because I wanted to see everything that was happening). I discovered medical non-fiction–the terrific “Annals of Medicine” series by New Yorker essayist

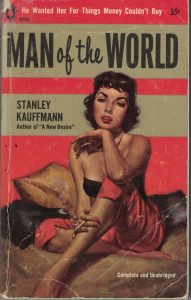

In the annals of 1950s cheesy paperback covers, surely Man of the World should feature somewhere. The sell line (“He wanted her for things money couldn’t buy”) drips innuendo, without actually saying anything. The babe on the cover is sultry. The promise that it’s “complete and unabridged” suggests that there are naughty bits that a more timid publisher might have expurgated. I found nothing that by current standards would be considered naughty.

In the annals of 1950s cheesy paperback covers, surely Man of the World should feature somewhere. The sell line (“He wanted her for things money couldn’t buy”) drips innuendo, without actually saying anything. The babe on the cover is sultry. The promise that it’s “complete and unabridged” suggests that there are naughty bits that a more timid publisher might have expurgated. I found nothing that by current standards would be considered naughty. When my parents met my father was married to a woman named Kit, who was a model, Vogue Magazine beautiful, and apparently a… difficult person. According to the novel, the protagonists (Nick and Delia) have a rather chaste thing going on–she lives with her mother, as my mother did–and they go to the movies or out to dinner. Early on in the book she decides this is going nowhere, and moves to New York. Okay, so far it jibes with family lore. My mother moved to New York and lived in a walk-up over a men’s haberdashery across 6th Avenue from the Women’s House of Detention on 9th Street. My father moved back to New York, having split with the beautiful Kit. He had an apartment-and-studio on 11th Street. Somehow they got back together.

When my parents met my father was married to a woman named Kit, who was a model, Vogue Magazine beautiful, and apparently a… difficult person. According to the novel, the protagonists (Nick and Delia) have a rather chaste thing going on–she lives with her mother, as my mother did–and they go to the movies or out to dinner. Early on in the book she decides this is going nowhere, and moves to New York. Okay, so far it jibes with family lore. My mother moved to New York and lived in a walk-up over a men’s haberdashery across 6th Avenue from the Women’s House of Detention on 9th Street. My father moved back to New York, having split with the beautiful Kit. He had an apartment-and-studio on 11th Street. Somehow they got back together.