Geothermal energy has huge potential to generate clean power – including from used oil and gas wells

Business Wire via AP

Moones Alamooti, University of North Dakota

As energy use rises and the planet warms, you might have dreamed of an energy source that works 24/7, rain or shine, quietly powering homes, industries and even entire cities without the ups and downs of solar or wind – and with little contribution to climate change.

The promise of new engineering techniques for geothermal energy – heat from the Earth itself – has attracted rising levels of investment to this reliable, low-emission power source that can provide continuous electricity almost anywhere on the planet. That includes ways to harness geothermal energy from idle or abandoned oil and gas wells. In the first quarter of 2025, North American geothermal installations attracted US$1.7 billion in public funding – compared with $2 billion for all of 2024, which itself was a significant increase from previous years, according to an industry analysis from consulting firm Wood Mackenzie.

As an exploration geophysicist and energy engineer, I’ve studied geothermal systems’ resource potential and operational trade-offs firsthand. From the investment and technological advances I’m seeing, I believe geothermal energy is poised to become a significant contributor to the energy mix in the U.S. and around the world, especially when integrated with other renewable sources.

A May 2025 assessment by the U.S. Geological Survey found that geothermal sources just in the Great Basin, a region that encompasses Nevada and parts of neighboring states, have the potential to meet as much as 10% of the electricity demand of the whole nation – and even more as technology to harness geothermal energy advances. And the International Energy Agency estimates that by 2050, geothermal energy could provide as much as 15% of the world’s electricity needs.

Wolfgang Kaehler/LightRocket via Getty Images

Why geothermal energy is unique

Geothermal energy taps into heat beneath the Earth’s surface to generate electricity or provide direct heating. Unlike solar or wind, it never stops. It runs around the clock, providing consistent, reliable power with closed-loop water systems and few emissions.

Geothermal is capable of providing significant quantities of energy. For instance, Fervo Energy’s Cape Station project in Utah is reportedly on track to deliver 100 megawatts of baseload, carbon-free geothermal power by 2026. That’s less than the amount of power generated by the average coal plant in the U.S., but more than the average natural gas plant produces.

But the project, estimated to cost $1.1 billion, is not complete. When complete in 2028, the station is projected to deliver 500 megawatts of electricity. That amount is 100 megawatts more than its original goal without additional drilling, thanks to various technical improvements since the project broke ground.

And geothermal energy is becoming economically competitive. By 2035, according to the International Energy Agency, technical advances could mean energy from enhanced geothermal systems could cost as little as $50 per megawatt-hour, a price competitive with other renewable sources.

Types of geothermal energy

There are several ways to get energy from deep within the Earth.

Hydrothermal systems tap into underground hot water and steam to generate electricity. These resources are concentrated in geologically active areas where heat, water and permeable rock naturally coincide. In the U.S., that’s generally California, Nevada and Utah. Internationally, most hydrothermal energy is in Iceland and the Philippines.

Some hydrothermal facilities, such as Larderello in Italy, have operated for over a century, proving the technology’s long-term viability. Others in New Zealand and the U.S. have been running since the late 1950s and early 1960s.

AP Photo/Julia Nikhinson

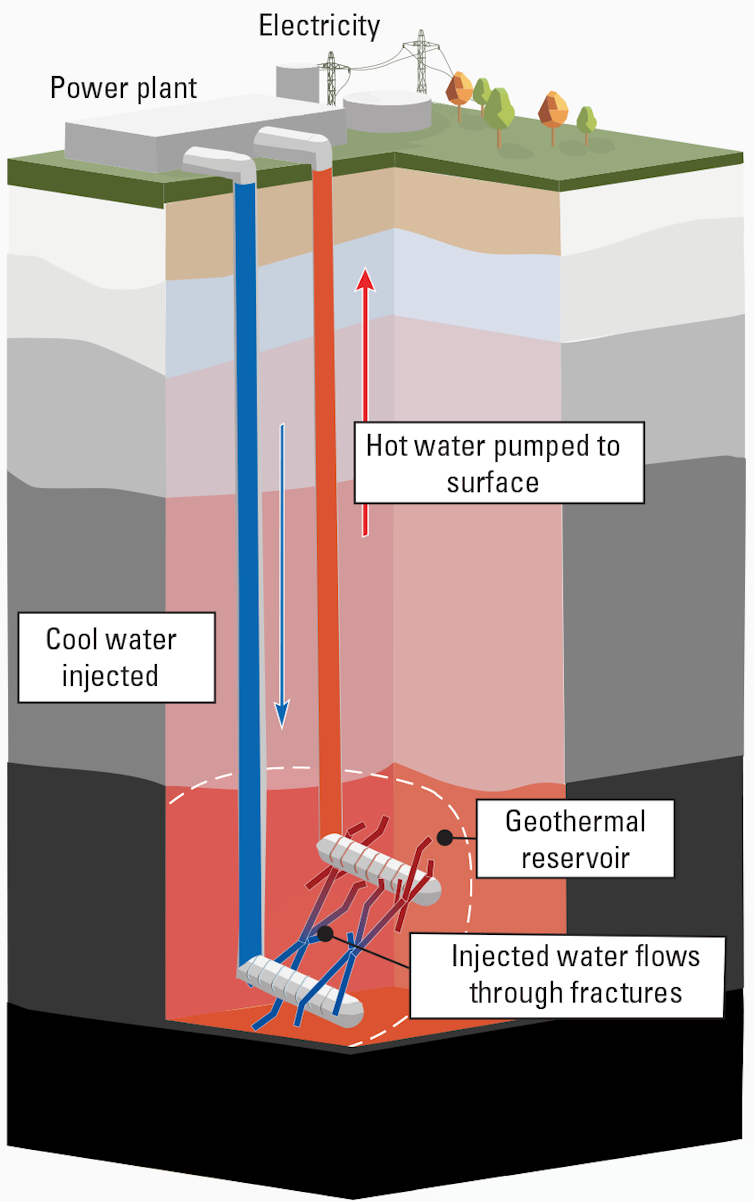

Enhanced geothermal systems effectively create electricity-generating hydrothermal processes just about anywhere on the planet. In places where there is not enough water in the ground or where the rock is too dense to move heat naturally, these installations drill deep holes and inject fluid into the hot rocks, creating new fractures and opening existing ones, much like hydraulic fracturing for oil and gas production.

A system like this uses more than one well. In one, it pumps cold water down, which collects heat from the rocks and then is pumped back up through another well, where the heat drives turbines. In recent years, academic and corporate research has dramatically improved drilling speed and lowered costs.

Ground source heat pumps do not require drilling holes as deep, but instead take advantage of the fact that the Earth’s temperature is relatively stable just below the surface, even just 6 or 8 feet down (1.8 to 2.4 meters) – and it’s hotter hundreds of feet lower.

These systems don’t generate electricity but rather circulate fluid in underground pipes, exchanging heat with the soil, extracting warmth from the ground in winter and transferring warmth to the ground in summer. These systems are similar but more efficient than air-source heat pumps, sometimes called minisplits, which are becoming widespread across the U.S. for heating and cooling. Geothermal heat pump systems can serve individual homes, commercial buildings and even neighborhood or business developments.

Direct-use applications also don’t generate electricity but rather use the geothermal heat directly. Farmers heat greenhouses and dry crops; aquaculture facilities maintain optimal water temperatures; industrial operations use the heat to dehydrate food, cure concrete or other energy-intensive processes. Worldwide, these applications now deliver over 100,000 megawatts of thermal capacity. Some geothermal fluids contain valuable minerals; lithium concentrations in the groundwater of California’s Salton Sea region could potentially supply battery manufacturers. Federal judges are reviewing a proposal to do just that, as well as legal challenges to it.

Researchers are finding new ways to use geothermal resources, too. Some are using underground rock formations to store energy as heat when consumer demand is low and use it to produce electricity when demand rises.

Some geothermal power stations can adjust their output to meet demand, rather than running continuously at maximum capacity.

Geothermal sources are also making other renewable-energy projects more effective. Pairing geothermal energy with solar and wind resources and battery storage are increasing the reliability of above-ground renewable power in Texas, among other places.

And geothermal energy can power clean hydrogen production as well as energy-intensive efforts to physically remove carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, as is happening in Iceland.

U.S. Geological Survey

Geothermal potential in the US and worldwide

Currently, the U.S. has about 3.9 gigawatts of installed geothermal capacity, mostly in the West. That’s about 0.4% of current U.S. energy production, but the amount of available energy is much larger, according to federal and international engineering assessments.

And converting abandoned oil and gas wells for enhanced geothermal systems could significantly increase the amount of energy available and its geographic spread.

One example is happening in Beaver County, in the southwestern part of Utah. Once a struggling rural community, it now hosts multiple geothermal plants that are being developed to both demonstrate the potential and to supply electricity to customers as far away as California.

Those projects include repurposing idle oil or gas wells, which is relatively straightforward: Engineers identify wells that reach deep, hot rock formations and circulate water or another fluid in a closed loop to capture heat to generate electricity or provide direct heating. This method does not require drilling new wells, which significantly reduces setup costs and environmental disruption and accelerates deployment.

There are as many as 4 million abandoned oil and gas wells across the U.S., some of which could shift from being fossil fuel infrastructure into opportunities for clean energy.

Challenges and trade-offs

Geothermal energy is not without technical, environmental and economic hurdles.

Drilling is expensive, and conventional systems need specific geological conditions. Enhanced systems, using hydraulic fracturing, risk causing earthquakes.

Overall emissions are low from geothermal systems, though the systems can release hydrogen sulfide, a corrosive gas that is toxic to humans and can contribute to respiratory irritation. But modern geothermal plants use abatement systems that can capture up to 99.9% of hydrogen sulfide before it enters the atmosphere.

And the systems do use water, though closed-loop systems can minimize consumption.

Building geothermal power stations does require significant investment, but its ability to deliver energy over the long term can offset many of these costs. Projects like those undertaken by Fervo Energy show that government subsidies are no longer necessary for a project to get funded, built and begin generating energy.

Despite its challenges, geothermal energy’s reliability, low emissions and scalability make it a vital complement to solar and wind – and a cornerstone of a stable, low-carbon energy future.![]()

Moones Alamooti, Assistant Professor of Energy and Petroleum Engineering, University of North Dakota

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Continue reading “Reprint: New (Green!) Energy From Old Gas Wells”…