Putting pig organs in people is OK in the US, but growing human organs in pigs is not – why is that?

wildpixel/iStock via Getty Images Plus

Monika Piotrowska, University at Albany, State University of New York

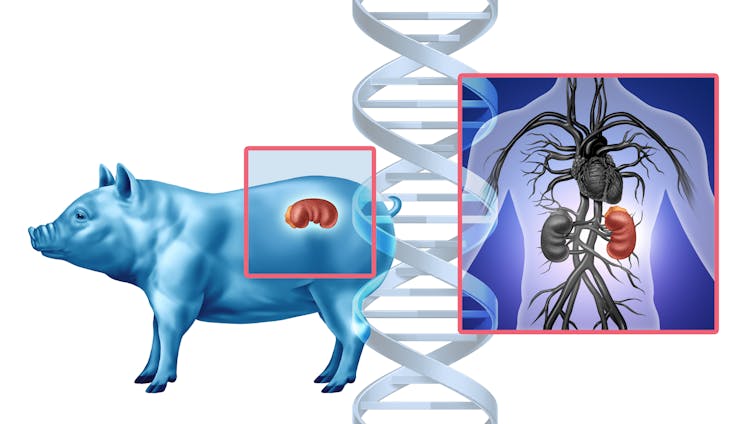

In a New York operating room one day in October 2025, doctors made medical history by transplanting a genetically modified pig kidney into a living patient as part of a clinical trial. The kidney had been engineered to mimic human tissue and was grown in a pig, as an alternative to waiting around for a human organ donor who might never come. For decades, this idea lived at the edge of science fiction. Now it’s on the table, literally.

The patient is one of six taking part in the first clinical trial of pig-to-human kidney transplants. The goal: to see whether gene-edited pig kidneys can safely replace failing human ones.

A decade ago, scientists were chasing a different solution. Instead of editing the genes of pigs to make their organs human-friendly, they tried to grow human organs – made entirely of human cells – inside pigs. But in 2015 the National Institutes of Health paused funding for that work to consider its ethical risks. The pause remains today.

As a bioethicist and philosopher who has spent years studying the ethics of using organs grown in animals – including serving on an NIH-funded national working group examining oversight for research on human-animal chimeras – I was perplexed by the decision. The ban assumed the danger was making pigs too human. Yet regulators now seem comfortable making humans a little more pig.

Why is it considered ethical to put pig organs in humans but not to grow human organs in pigs?

Urgent need drives xenotransplantation

It’s easy to overlook the desperation driving these experiments. More than 100,000 Americans are waiting for organ transplants. Demand overwhelms supply, and thousands die each year before one becomes available.

For decades, scientists have looked across species for help – from baboon hearts in the 1960s to genetically altered pigs today. The challenge has always been the immune system. The body treats cells it does not recognize as part of itself as invaders. As a result, it destroys them.

A recent case underscores this fragility. A man in New Hampshire received a gene-edited pig kidney in January 2025. Nine months later, it had to be removed because its function was declining. While this partial success gave scientists hope, it was also a reminder that rejection remains a central problem for transplanting organs across species, also known as xenotransplantation.

Researchers are attempting to work around transplant rejection by creating an organ the human body might tolerate, inserting a few human genes and deleting some pig ones. Still, recipients of these gene-edited pig organs need powerful drugs to suppress the immune system both during and long after the transplant procedure, and even this may not prevent rejection. Even human-to-human transplants require lifelong immunosuppressants.

That’s why another approach – growing organs from a patient’s own cells – looked promising. This involved disabling the genes that let pig embryos form a kidney and injecting human stem cells into the embryo to fill the gap where a kidney would be. As a result, the pig embryo would grow a kidney genetically matched to a future patient, theoretically eliminating the risk of rejection.

Although simple in concept, the execution is technically complex because human and pig cells develop at different speeds. Even so, five years prior to the NIH ban, researchers had already done something similar by growing a mouse pancreas inside a rat.

Cross-species organ growth was not a fantasy – it was a working proof of concept.

Ethics of creating organs in other species

The worries motivating the NIH ban in 2015 on inserting human stem cells into animal embryos did not come from concerns about scientific failure but rather from moral confusion.

Policymakers feared that human cells might spread through the animal’s body – even into its brain – and in so doing blur the line between human and animal. The NIH warned of possible “alterations of the animal’s cognitive state.” The Animal Legal Defense Fund, an animal advocacy organization, argued that if such chimeras gained humanlike awareness, they should be treated as human research subjects.

The worry centers on the possibility that an animal’s moral status – that is, the degree to which an entity’s interests matter morally and the level of protection it is owed – might change. Higher moral status requires better treatment because it comes with vulnerability to greater forms of harm.

Think of the harm caused by poking an animal that’s sentient compared to the harm caused by poking an animal that’s self-conscious. A sentient animal – that is, one capable of experiencing sensations such as pain or pleasure – would sense the pain and try to avoid it. In contrast, an animal that’s self-conscious – that is, one capable of reflecting on having those experiences – would not only sense the pain but grasp that it is itself the subject of that pain. The latter kind of harm is deeper, involving not just sensation but awareness.

Thus, the NIH’s concern is that if human cells migrate into an animal’s brain, they might introduce new forms of experience and suffering, thereby elevating its moral status.

AP Photo/Shelby Lum

The flawed logic of the NIH ban

However, the reasoning behind the NIH’s ban is faulty. If certain cognitive capacities, such as self-consciousness, conferred higher moral status, then it follows that regulators would be equally concerned about inserting dolphin or primate cells into pigs as they are about inserting human cells. They are not.

In practice, the moral circle of beings whose interests matter is drawn not around self-consciousness but around species membership. Regulators protect all humans from harmful research because they are human, not because of their specific cognitive capacities such as the ability to feel pain, use language or engage in abstract reasoning. In fact, many people lack such capacities. Moral concern flows from that relationship, not from having a particular form of awareness. No research goal can justify violating the most basic interests of human beings.

If a pig embryo infused with human cells truly became something close enough to count as a member of the human species, then current research regulations would dictate it’s owed human-level regard. But the mere presence of human cells doesn’t make pigs humans.

The pigs engineered for kidney transplants already carry human genes, but they aren’t called half-human beings. When a person donates a kidney, the recipient doesn’t become part of the donor’s family. Yet current research policies treat a pig with a human kidney as if it might.

There may be good reasons to object to using animals as living organ factories, including welfare concerns. But the rationale behind the NIH ban that human cells could make pigs too human rests on a misunderstanding of what gives beings – and human beings in particular – moral standing.

This article was updated to correct the location and date of the first pig kidney transplant clinical trial.![]()

Monika Piotrowska, Associate Professor of Philosophy, University at Albany, State University of New York

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Continue reading “Reprint: The Moral Ambiguity of Xenotransplantation”…