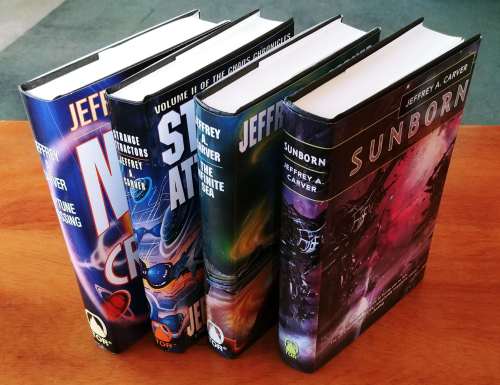

The stories that gave rise to The Seven-Petaled Shield began with my love of horses and a special exhibit at the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County of the art of the nomads of the Eurasian steppe. I marveled at the beautiful gold artifacts of the Scythians, depicting horses, elk, and snow leopards, and the lives and adventures of these people. The Greek historian Herodotus described the Scythians as “invincible and inaccessible,” and Thucydides asserted, “there is none which can make a stand against the Scythians if they all act in concert.” This world, its people, and its marvelous horses practically begged for stories to be written about them.

The stories that gave rise to The Seven-Petaled Shield began with my love of horses and a special exhibit at the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County of the art of the nomads of the Eurasian steppe. I marveled at the beautiful gold artifacts of the Scythians, depicting horses, elk, and snow leopards, and the lives and adventures of these people. The Greek historian Herodotus described the Scythians as “invincible and inaccessible,” and Thucydides asserted, “there is none which can make a stand against the Scythians if they all act in concert.” This world, its people, and its marvelous horses practically begged for stories to be written about them.

The Scythians were only one of many nomadic horse-faring peoples who roamed the Central Asian steppe from the beginning of the first millennium before the Common Era into the 20th Century. Sarmatians, Cimmerians, Massagetae, Alani, and many others were followed by such groups as the Hun, Kazars, Uzbeks, Bulgars, and Magyars. Although these peoples differed in culture, language, religion, and place of origin, they shared the  characteristics of nomadic horse folk. They were highly mobile, superb archers, and their survival depended on their horses.

characteristics of nomadic horse folk. They were highly mobile, superb archers, and their survival depended on their horses.

I based the Azkhantian horses on those used by these historical peoples. Typically, their horses were small and hardy, not particularly beautiful but capable of great endurance. Some sources compared them to “primitive” types like Przewalski’s Horse. As I developed the Azkhantian culture more, I delved into the literature about Mongolian horses. I wanted a breed that could withstand extremes of weather, thrive on poor food and scarce water, and able to cover great distances, equivalent to or exceeding modern endurance races. Although the 20th Century brought many changes to Mongolia itself, I found photographic records and journals from travelers who visited this area before or shortly following World War I, when mechanized technology had made few if any inroads into the steppe. The Long Riders Press has reprinted a number of these travel journals, in particular Mongolian Adventure: 1920s Danger and Escape Among the Mounted Nomads of Central Asia. Henning Haslund’s tales of his travels through pre-industrialized Mongolia provided not only descriptions of the peoples, landscapes, animals, and traditions, but examples of the poetry and songs, the latter with staff notation. “The Horse With the Velvet Back” and “The Dear Little Golden Horse” are examples of the importance of horses in this culture.

Haslund wrote: “Most Mongolian horses are finely built, but the animals from the mountain districts often remind one of the Ardennes horses on a smaller scale. The average Mongolian horse stands barely fourteen hands, but what it can do on long journeys is unparalleled. … My new horse was … small but powerful, and had such control over his legs that he always set them with precision in the right place. If he snorted and refused to go forward, it always turned out that he was standing on the edge of a place where there was a risk of slipping.”

Haslund wrote: “Most Mongolian horses are finely built, but the animals from the mountain districts often remind one of the Ardennes horses on a smaller scale. The average Mongolian horse stands barely fourteen hands, but what it can do on long journeys is unparalleled. … My new horse was … small but powerful, and had such control over his legs that he always set them with precision in the right place. If he snorted and refused to go forward, it always turned out that he was standing on the edge of a place where there was a risk of slipping.”

Shannivar’s favorite horse, Eriu, was modeled on Haslund’s description. Here she races her cousin, Alsanobal:

Alsanobal gave the red his head, and they raced back the way they had come. Shannivar tapped Eriu with her heels. The black gathered his hindquarters under him, then burst into a full-out gallop. The coarse hairs of his mane whipped across Shannivar’s face. She leaned over his forequarters, secretly pleased that they would have their race after all.

Eriu’s speed was like fire, like silk, as intoxicating as k’th. Even on the rough downhill footing, he never missed a step. The air itself sustained him.

By day, you are my wings, the poet sang to his favorite steed. By night, you never fail me.

They plunged downhill, caught Alsanobal on his red, and passed them. Shannivar whooped in triumph.

I based the Azkhantian horses on the Mongolian breeds, for their hardiness and endurance, their weather-sense and nimbleness. Given the extent of the inhabited steppe, it made sense to me that there would be variation among the types of horses, not just of conformation and temperament, but the same sorts of characteristics that mark the difference between breeds. I introduced two particular variations: tundra horses and gaited horses. The Tundra Horse was a strain of “primitive” horse (like Przewalski’s Horse) living in the Arctic Circle, sighted as late as the mid 1960s (in northeastern Siberia). The Yakut pony has the same geographical distribution and is able to survive extremely severe climactic conditions. So I mounted the northernmost of the Azkhantian tribes on these shaggy white horses.

I became interested in “gaited” horses through a dear friend, a lover of Tennessee Walking Horses. All horses have gaits (walk, trot, canter, gallop) but some are capable of ambling, a four-beat, extremely smooth and often rapid pattern of movement. These are genetically linked (it’s a mutation on the gene DMRT3), the way the propensity to either trot (front and hind feet move alternately) or pace (front and hind feet move together) is. When I began to research gaited breeds, I realized that the special smooth gaits were actually a group of distinct patterns, and that some version of a soft-stepping horse can be found throughout the world, from the Peruvian Paso to the Missouri Fox Trotter, the Icelandic horse, the Indian Marwari, German Aegidienberger, and Greek Messara ponies.

Just as people are not uniform in language, customs, food, or many other aspects, neither are animals or Asiatic wild ass (Equus hemionus). In our own history, doubt remains whether onagers were ever domesticated, being thought too “unruly.” I thought a strong, hardy, intelligent equine – quite amenable to training, for this is a fantasy world — might provide a reasonable alternative to the horse.

The Gelon “stone-dwellers,” to the southwest of the steppe, would not use the same type of animal. Gelon was originally loosely based on the Roman Empire, with an Italian climate – much warmer and wetter than the steppe. I decided to not stick with horses, but to explore parallel agricultural evolution and use historical precedent in giving the Gelon a strong preferences for the onager.

The carving of the Mongolian horse is by Taylor Weidman/The Vanishing Cultures Project and licensed under Creative Commons. The photo of the grazing Mongolian horses is by Brücke-Osteuropa and is in the public domain. The image of the onager is in the public domain.

The internet is practically an engraved invitation to indulge in gossip and rumor. It’s so easy to blurt out whatever thoughts come to mind. Once posted, these thoughts take on the authority of print (particularly if they appear in some book-typeface-like font). Have you ever noticed how much easier it is to question something when it appears in Courier than when it’s in Times New Roman? For the poster of the thoughts comes the thrill of instant publication. Only in the aftermath, when untold number have read our blurtings and others have linked to them, not to mention all the comments and comments-on-comments, do we draw back and realize that we may not have acted with either wisdom or kindness.

The internet is practically an engraved invitation to indulge in gossip and rumor. It’s so easy to blurt out whatever thoughts come to mind. Once posted, these thoughts take on the authority of print (particularly if they appear in some book-typeface-like font). Have you ever noticed how much easier it is to question something when it appears in Courier than when it’s in Times New Roman? For the poster of the thoughts comes the thrill of instant publication. Only in the aftermath, when untold number have read our blurtings and others have linked to them, not to mention all the comments and comments-on-comments, do we draw back and realize that we may not have acted with either wisdom or kindness.

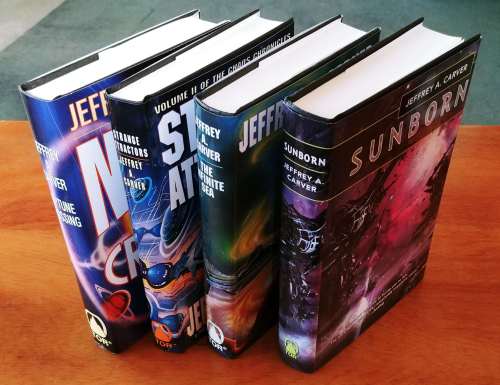

It’s the holiday season, or so I’m told. I have signally failed to organize present-giving this year–to the point where my husband and I were yelling “I dunno, what do YOU want?” at each other from different rooms Saturday afternoon. The one thing I have done is to make some books as gifts. This is utterly self-serving: I found a couple of bookbinding projects that I wanted to do, and thought: who would like the end project? And there you go.

It’s the holiday season, or so I’m told. I have signally failed to organize present-giving this year–to the point where my husband and I were yelling “I dunno, what do YOU want?” at each other from different rooms Saturday afternoon. The one thing I have done is to make some books as gifts. This is utterly self-serving: I found a couple of bookbinding projects that I wanted to do, and thought: who would like the end project? And there you go. The stories that gave rise to The Seven-Petaled Shield began with my love of horses and a special exhibit at the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County of the art of the nomads of the Eurasian steppe. I marveled at the beautiful gold artifacts of the Scythians, depicting horses, elk, and snow leopards, and the lives and adventures of these people. The Greek historian Herodotus described the Scythians as “invincible and inaccessible,” and Thucydides asserted, “there is none which can make a stand against the Scythians if they all act in concert.” This world, its people, and its marvelous horses practically begged for stories to be written about them.

The stories that gave rise to The Seven-Petaled Shield began with my love of horses and a special exhibit at the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County of the art of the nomads of the Eurasian steppe. I marveled at the beautiful gold artifacts of the Scythians, depicting horses, elk, and snow leopards, and the lives and adventures of these people. The Greek historian Herodotus described the Scythians as “invincible and inaccessible,” and Thucydides asserted, “there is none which can make a stand against the Scythians if they all act in concert.” This world, its people, and its marvelous horses practically begged for stories to be written about them. characteristics of nomadic horse folk. They were highly mobile, superb archers, and their survival depended on their horses.

characteristics of nomadic horse folk. They were highly mobile, superb archers, and their survival depended on their horses.