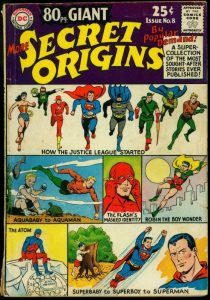

Once I got reading under my belt, I couldn’t do enough of it–books, stories, cereal boxes, comic books. I gobbled up story like I was starving for it, initially uncritically, but fairly soon starting to think about why stories worked/didn’t work for me. In this I had a partner: my brother Clem. He and I amassed a comic book collection of perhaps 2000 well-worn, repeatedly read comics–most, but not all of them DC (the home of Superman and Batman). Clem and I haunted the smoke shop at the corner, where the new comics came in every… I think it was Tuesday… and conspired over which one of us would buy which. We took them home and read the them and then we talked over them. Clem, a far better artist than I will ever be, led the way in discussing the art. One of our favorite riding-on-the-subway games was to identify people who looked like they were drawn by specific artists. “Look, its a Gil Kane nose!” Or a Curt Swan chin or… God help you, a Wayne Boring face (Boring’s faces were heavily rectangular, with long noses, and always looked outraged or surprised).

Once I got reading under my belt, I couldn’t do enough of it–books, stories, cereal boxes, comic books. I gobbled up story like I was starving for it, initially uncritically, but fairly soon starting to think about why stories worked/didn’t work for me. In this I had a partner: my brother Clem. He and I amassed a comic book collection of perhaps 2000 well-worn, repeatedly read comics–most, but not all of them DC (the home of Superman and Batman). Clem and I haunted the smoke shop at the corner, where the new comics came in every… I think it was Tuesday… and conspired over which one of us would buy which. We took them home and read the them and then we talked over them. Clem, a far better artist than I will ever be, led the way in discussing the art. One of our favorite riding-on-the-subway games was to identify people who looked like they were drawn by specific artists. “Look, its a Gil Kane nose!” Or a Curt Swan chin or… God help you, a Wayne Boring face (Boring’s faces were heavily rectangular, with long noses, and always looked outraged or surprised).

It’s possible that I led the way talking about plot. This led to us becoming letter-hacks–the people who write in to the letter columns in comics to ask questions, bring up continuity nitpicks, or discuss plot and characterization. Probably my earliest critical thinking regarding writing began when I wrote to the letter columns. Sometimes our letters appeared in print. Sometimes other letter-hacks took issue with my opinion, or with my brother’s. Dialogue! It was heady stuff.

In the same way, Clem and I would talk over episodes of TV we watched (and we watched a lot). I don’t remember too much of our conversations–my brother remembers more. But a number of them circled around why a writer wrote a scene in a particular way, why the writer included a specific story-line or introduced a comic character into what was otherwise a dramatic moment. Network TV was not exactly dazzling, writing-wise, but a lot of it was solid entertainment (barring the ghastly attempts to be ‘relevant’ which only exposed–even to my 10-year-old eyes, the breathless cluelessness of the writers). It was a fertile field for these “why did that work/why did that not work” conversations. I didn’t think I was learning anything, but it appears that I was.

Because of all this, I probably let my kids watch too much TV. Because by the time I had kids I realized what watching Too Much TV and talking it over had given me: nascent critical skills. So I sat through almost all of the stuff my daughters watched (even ::shudder:: Hannah Montana) and we had conversations about them. Adjusted for their age and the material, some of these conversations were pretty smart. One example (stop me if I’ve told you this): when she was 11 my older daughter walked out of The Fellowship of the Rings with me (she hadn’t read the book, but had watched the hell out of the film) and treated me to a 15 minute dissertation on the need, plot-wise, for Boromir to die to redeem the fellowship.

Lest you think she was a prodigy (okay, I’m their mother) her sister, aged 7, watched Sense and Sensibility and, talking about why everyone was so down on Marianne Dashwood for riding around with Willoughby, came up with the brilliant formulation of “sex cooties!” As in: “if Marianne rides around with a guy she’s not married to, people will think she has sex cooties.” I swear to God.

All this from growing up with me, and her father, and her sister, and talking endlessly about why the story needs what it needs.

My mother once called my comic books junk culture. Maybe so–but out of that junk some good stuff can come.