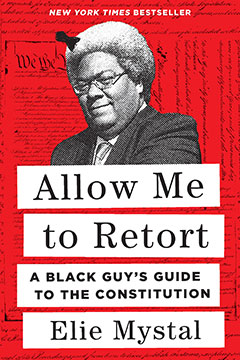

I reviewed Elie Mystal’s book Allow Me to Retort: A Black Guy’s Guide to the Constitution for Washington Lawyer, the magazine of the District of Columbia Bar Association. Since it’s a brilliant analysis of the issues underlying the political turmoil in the United States today and also one of the best books I’ve read all year, I decided to share my review here on the Treehouse.

I reviewed Elie Mystal’s book Allow Me to Retort: A Black Guy’s Guide to the Constitution for Washington Lawyer, the magazine of the District of Columbia Bar Association. Since it’s a brilliant analysis of the issues underlying the political turmoil in the United States today and also one of the best books I’ve read all year, I decided to share my review here on the Treehouse.

When it comes to the U.S. Constitution, Elie Mystal does not mince words, beginning his book with this sentence: “Our Constitution is not good.” While such a statement might be heresy to many lawyers, this witty, profane, and well-argued book makes a strong case for recognizing the flaws in our founding document and doing what we can to fix it.

Mystal, a Harvard-educated lawyer, writes from the viewpoint of someone the Constitution was “designed to ignore,” and to that end takes strong issue with the originalists, finding no reason to discern the intent of those who wrote a document counting enslaved people as three-fifths of a person. Further, as he discusses in a chapter entitled “The Most Important Part,” the compromises made while drafting the Constitution gave way in a bloody Civil War less than a hundred years after it was adopted. “The Union survived the Civil War, but its slavers’ Constitution did not,” he points out.

The Reconstruction amendments — the 13th, 14th, and 15th — changed things dramatically. Mystal contends that those additions, together with the 19th Amendment, recast the Constitution into something “not utterly unredeemable.”

Make no mistake — Mystal does want to redeem it, and he thinks those four amendments can do just that. “But white people won’t let them,” he says, writing that the 15th Amendment should prohibit voter suppression laws and that equal protection as set out in the 14th Amendment should protect him and other Black people from racist harassment by the police.

The book focuses on the amendments because they are the part of the Constitution that affects people directly. In the chapter on the Fourth Amendment, Mystal argues that the “reasonable suspicion” standard that allows police to do warrantless searches means that officers will act on their implicit — and explicit — biases. While racial profiling is technically prohibited (based on the 14th Amendment), the necessity to prove that in individual cases allows stop-and-frisk laws to stay in effect and, all too often, be applied in racist ways. As a Black man in the United States, Mystal has personal experience with the effects of such laws, and he does not apologize for the fact that he takes them, and the court decisions that allow them, very personally.

He also discusses the way peremptory challenges, which require no reason, are used to keep Black people off juries, concluding that Justice Thurgood Marshall was right in his concurring opinion in Batson v. Kentucky. While the 1986 ruling by Justice Lewis Powell Jr. prohibits challenging a juror solely on grounds of race, Justice Marshall said that it would not end discrimination in peremptory challenges. “That goal can be accomplished only by eliminating peremptory challenges entirely.”

Mystal addresses other issues of discrimination. His section on abortion rights contends that “equal protection” makes it clear that if women are people, they have the right to control their bodies. He also defends the right-to-privacy argument that underlies much of reproductive rights litigation.

His discussion on the use of religious freedom arguments to allow people to refuse to do business with LGBTQ persons makes an interesting point. The bakery that would not provide a cake for a same-sex wedding could have argued that it was protected, as a creative enterprise, under free speech, but that argument would not apply to clerks who refuse to issue marriage licenses. Mystal argues that free speech arguments do not “get bigots where they want to go.”

Those who have read Mystal’s regular pieces on legal issues in The Nation, watched his commentary on news programs, or followed his wonderfully snarky Twitter account will not be surprised that he strongly advocates expanding the U.S. Supreme Court, suggesting the addition of 20 justices with the idea that they would sit in panels much as the courts of appeal do. He is also an advocate of term limits.

Mystal wrote this book for a lay audience and does a superb job of presenting complex issues in clear English without watering them down. Armed with this book, anyone can make an argument against, say, voter suppression laws.

But that doesn’t mean this isn’t a useful book for lawyers. Mystal’s willingness to question the system provides a good counterbalance to the legal tendency to take the way things are as a given. And his bluntness on racism and the unforgivable sin of slavery underlying the establishment of our country makes it clear that such problems are something we can no longer afford to ignore.