I am re-reading a book that was published in 1969 (Rumer Godden’s In This House of Brede*). As I was enjoying the things that go along with a re-read (the comfort of a known plot which allows you to sink into the characters, renewed enjoyment of the writing, discoveries of things you slid past on the first readings) I realized that I was also reminded of the way the books of my youth were made, which is different from the way they are generally made today. Lemme ‘splain.

I am re-reading a book that was published in 1969 (Rumer Godden’s In This House of Brede*). As I was enjoying the things that go along with a re-read (the comfort of a known plot which allows you to sink into the characters, renewed enjoyment of the writing, discoveries of things you slid past on the first readings) I realized that I was also reminded of the way the books of my youth were made, which is different from the way they are generally made today. Lemme ‘splain.

For eight years I was the Operations Manager at the American Bookbinders Museum. In practice, this title included a bunch of functions including Design Department, Chief Docent, Rental Manager, and Covid Czar–but the important thing is that I learned to look at the objects which had been, for my entire life, vessels for story. Looking at this book (which is a decommissioned library book with WITHDRAWN stamped on the inside cover, still in its mylar jacket cover) it’s… elderly. Probably the same vintage as many of the books I took out of the library when I was a teenager: full “adult size” books from the Adult section of the library (this one is the 6″x9″ trim associated with the top of the publisher’s list–what the publisher believes will be important and sell well, as Brede did). And it swivels a little because the binding has loosened over the years.

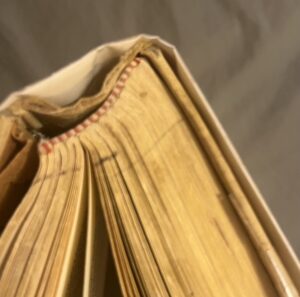

Until the advent of paperbacks, books (almost all, at least in the Western world) were sewn. In the photo on the right you can see the stitches at about 1″ intervals. (Here’s a good description of the anatomy of a sewn book, from the Princeton Public Library). The structure of a book is meant to keep all the pages together in the correct order, safely. Sewing signatures (or gathers) into a larger text block, was the way this was done for a thousand years. Most sewn books have a hollow spine (which is to say, the sewn spine is flexible, and the spine cover “floats” above it to protect the spine without making the structure more rigid. Then came the paperback, where the pages are glued together in a block. This has some serious benefits, but paperbacks are ephemeral. Granted, I still have paperbacks I

Until the advent of paperbacks, books (almost all, at least in the Western world) were sewn. In the photo on the right you can see the stitches at about 1″ intervals. (Here’s a good description of the anatomy of a sewn book, from the Princeton Public Library). The structure of a book is meant to keep all the pages together in the correct order, safely. Sewing signatures (or gathers) into a larger text block, was the way this was done for a thousand years. Most sewn books have a hollow spine (which is to say, the sewn spine is flexible, and the spine cover “floats” above it to protect the spine without making the structure more rigid. Then came the paperback, where the pages are glued together in a block. This has some serious benefits, but paperbacks are ephemeral. Granted, I still have paperbacks I stole borrowed from my parents that were published in the 1950s, but most paperbacks were not expected to live very long. Their structure did not hold up (when I worked in Production at Tor Books we would get letters calling us uncomplimentary things because eventually the spines of really thick paperbacks would begin to split or separate–this was a function of the process and the glues then available).

Then, in the mid-late 1990s, the technology changed. The glue used in “perfect” binding (that’s what paperback bindings are called in the trade) improved hugely. Wonder why trade paperbacks suddenly went from being a rarity to being a dominant format? It’s because suddenly you could do a trade-sized book at a price that was much more buyer-friendly, without the fear that the latest Big Horror (or Fantasy or Biography) Book would fall apart while you’re reading it.

So picking up In This House of Brede and really looking at it was a bit of a time capsule for me. The original purpose of books–all books–was as a container for information. Vessels, as I said above. You wanted to protect the information and keep it organized so that you can move back and forth as needed (the codex form on which the modern book is based makes that easier than the earlier format, the scroll). And you wanted to be able to keep that protected information out of the hands of the people you didn’t want to have it, whether because it would give them an advantage, or because you didn’t think they were worthy of it. The information in those books–whether it was an epic poem or a history or an alchemical formulary–had value. By the time this particular book was published, the point was not to keep this story or any other out of the public hands–it was to make it widely, broadly, lucratively available. The shift in binding technology helped with that. (But I can still pick up this book and sniff it and be transported back to 14-year-old me at the library.)

There’s a lot of agitation in certain quarters about keeping information out of the hands of… oh, children, or innocents, or people who think. Everyone. I’m hoping that technology–the genie that’s been let out of the bottle–will make that impossible in the long run. Fingers crossed.

__________

* I have, for all my total lack of religious background, a fascination with monastic practice and life. Don’t ask me why.