Yep, it’s another month, another installment of “Better Humaning Through Dogs.”

Generally, I try to write about the positive elements of dog companionship – or at least, the interesting ones. And generally, people who love or work with dogs understand the psychology of these animals, or are willing to learn.

But sometimes, I swear to dog, er, god, media makes education difficult, and I just have to scream.

Recently I saw a People magazine article, one of those clickbait headlines squibs, about a puppy so protective of a new family member, it wouldn’t even let the baby‘s mama touch baby. And it was, as these things always are reported, done up in a sweetly twee, isn’t it cute! tone. Isn’t that a good dog?

No, it’s not cute. At that level, it’s called resource guarding, and it’s not something you should be encouraging in your dogs, OK? (Or your cats, for that matter.) Yes, dogs are excellent guardians, and are often very careful and watchful around the younger members of their pack, four or two-legged.

But when the family dog gets upset when anyone else comes near the baby, to the point of growling or showing teeth, Rover or Fluffy isn’t being protective over your offspring. Rover or Fluffy is claiming them as their property, their territory. That’s a version of resource guarding, and it’s not a healthy situation, much less “cute.”

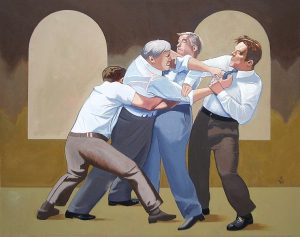

Resource guarding, within context, isn’t a bad thing. Between dogs, it’s annoyingly common – I’ve seen this play out more times than I like, working with shelter dogs, with friend’s dogs, with my own dog. Between dogs, its a way of laying down boundaries: this is mine and I will share it, this is mine and I will not. Most dogs will recognize and accept those boundaries, and back down (when they don’t, that’s when you get dog fights).

But humans, for the most part, are clueless about the warning signs, and very bad about backing off. And no, you can’t count on your dog recognizing you, and knowing that you are to be trusted. Not in the instant of reaction, anyway. To the resource guarding dog’s mind, everything is a potential threat to their possession of the beloved object. Even another pack member, maybe even alpha pack members. And they’re not going to sit back and rationally think it out; they’re going to respond the way they’re designed to, quickly, efficiently, and potentially bloodily.

And a dog’s idea of defensive behavior? Involves teeth.

That means anyone attempting to reach for the child, in the case of this article, or a person in need of medical care, or even a partner attempting to show affection, risks getting bitten. Maybe badly.

So yeah, articles like the one I saw are the worst kind of narrative, assigning emotions and motives inaccurately, and making it seem like a good thing. A trained guard dog does not behave that way. An untrained guarding dog is a danger to everybody. Including that dog. Because you know what too-often happens to dogs that bite. Even if they’re not at fault.

So yeah, please, please. If you have a dog that is showing signs of resource guarding against humans, particularly if they’re resource guarding another human, get them (and you) professional help to stop it.

The life you save may be theirs.

for more information, I’d suggest starting here.

I live with a geriatric half-Dalmatian former-athlete dog. She is sweet and stubborn and ridiculous… and approaching the end of her sell-by date. I had not thought to see my own mortality mirrored in my dog, but there it is. She’s not my first dog, but for a variety of reasons I didn’t get to see my earlier dogs age.

I live with a geriatric half-Dalmatian former-athlete dog. She is sweet and stubborn and ridiculous… and approaching the end of her sell-by date. I had not thought to see my own mortality mirrored in my dog, but there it is. She’s not my first dog, but for a variety of reasons I didn’t get to see my earlier dogs age. Stories can heal and transform us. They can also become beacons of hope.

Stories can heal and transform us. They can also become beacons of hope.

It’s blackberry season, and as is my custom at this time, I went out this morning to pick from the brambles along our little country road. (We have our own patch, but the berries ripen later because it’s in a shadier place.) I try to do this early, when it’s cool and I’m not having to squint into the sun for the higher branches. As I picked, I thought about the story I’m working on (and currently stalled on 2 scenes-that-need-more), and also writing in general.

It’s blackberry season, and as is my custom at this time, I went out this morning to pick from the brambles along our little country road. (We have our own patch, but the berries ripen later because it’s in a shadier place.) I try to do this early, when it’s cool and I’m not having to squint into the sun for the higher branches. As I picked, I thought about the story I’m working on (and currently stalled on 2 scenes-that-need-more), and also writing in general.