I am supposed to be asleep. In six hours I have to wake up and buy all my fruit and vegetables at the farmers’ market. It’s the last day I can do this and… I’m tired. My body announced that we’re getting another heatwave. It announced this by pushing my mind into fastplay. Then I got excited by my thoughts: I finally had a reason for something that has been plaguing me for decades. This is why I am writing you all this blogpost at an unholy hour when I ought to be asleep. I’m not at all certain that anyone but me will be excited, but I’m very excited, so this is fair. The world is balanced.

Also, I may be entirely and completely wrong about everything I say here. If I am, please don’t just say “You’re wrong” – tell me how and why. (I’m a bit tired of being I’m wrong with no explanation. This is not you, this is the wider public which is full of opinions on all things Jewish right now. Most of the opinions are not nice.)

Once upon a time, in a moment a bit like the one we’re in now, when the rulers of France and its church demanded that all Jews be their kind of Jew, this view was challenged. “Their kind of Jew” was one which supported that particular branch of Christian theology and the rulers and all sorts of related things. By “supporting” some Jews were expected to engage in very specific debates that were not supposed to demonstrate truths, but demonstrate the Christian truths that were important in that moment and place.

The learned Jews of Paris and its nearby regions had little choice but to engage in the debate because, to be frank, Jews were not given a fair go. They were not full citizens with full rights. What they were is complex to explain so I’ll cheat a bit and explain one view of what Jews were expected to be. We were expected to be (and still are, in some circles) the remnant of those who witnessed the coming of the Messiah. We were important as people who had seen. But Jews are fractious and difficult and were a lot more than that, and, for a variety of reasons, the French king became very aware of this. He was a holy bloke, was Louis IX, and he loved showing off his piety. Place an image in your mind of a rather splendid thirteenth century French king. We will return to him.

Now we travel back in time. We will return to Louis IX.

The thing is, Jewish history is often part of the history of the lands where Jews live, but it also goes its own way. When something troubling happens, we respond.

Once upon a time (an earlier time) Judaism had the Written Law (the Torah) and Oral Law. There was trouble. Much change happened. This was when the Second Temple fell and Jews were enslaved and became part of the Roman Empire. It caused many learned folk to ask, “What happens if we lose all these experts who know the Oral Law?” They also asked, “What do we do without the Temple?” There were answers that had already been considered (because we had lost the Temple once before, I suspect), but that’s a different story. Related, but different. Stories breed stories. History is never simple. And Gillian is full of aphorisms today.

The learned folks who maintained the oral law began writing it down. It took a while. A long, long while. About five hundred years.

Not only was there a lot of oral law to write down, but learned Jews are, were, and always will be opinionated, so those doing the documentation added stuff and it was talked about and… the Talmud is the most amazing document. One of the great feats of literature and story and argument and religion, all bound together into a wildly difficult set of books. I was once told that whoever studies the Talmud is learning about humanity, and to me that sounds about right.

The Talmud comes in two versions of considerably different lengths with considerably different material. One was written in what is now Iraq, by diaspora Jews, and the other was written in Jerusalem. Finally, finally, it was written down (handwritten, all those volumes written down then copied by scribes, one letter at a time) and, as far as I know (this is not something I know enough about) determinations were made about what words and thoughts were part of the official document. And so we had both the Torah and the Talmud in written versions, by the end of the early Middle Ages.

That wasn’t the end of it. Jewish culture contains story and discussions and finding a stupid example and using it to teach and a whole bunch of culture at its core. Also bad jokes. I find it very difficult to explain to the highly serious why one festival incorporates getting drunk and also mocking the story of the Book of Esther, but the heart of this sense of humour and the ability to take religion both very seriously and very lightly can be traced back through the Talmud. What happened next followed the general cultural lines of Jewish thought, and takes us right into the Middle Ages.

The Talmud in its modern printed version occupies whole walls of the houses of very highly learned religious people of Judaism (not me, I am not of the Jewish scholarly elite at all). It takes seven and a half years to read it through once in the regular way, at a page a day. It, in its modern version, is probably the longest written work every published. The Talmud is beyond brilliant and beyond stupid and the best way to read it is in discourse (and probably argument) with other people. I don’t know whether to be infuriated to amused at those idiots who share one page of translated extracts and say “Look how foul Judaism is: their holy book says this.” It’s using a few words to hide the whole document.

You can find a complete translation of the Talmud (but not of the one page that misleads) here. https://www.sefaria.org/texts/Talmud

The Torah is the law, and the Talmud is where the law is explained so that we know what to do with it. Medieval rabbis helped us understand how to interpret the Talmud, because placing yourself in front of thousands of pages with no guidance is the sure way to not understand the law.

This is where Europe joins the party. A bunch of learned European Jews gave ordinary Jews (such as myself) technical guides to help with the interpretation. The code breakers that most people know of and may use are the Mishneh Torah, written by Moses ben Maimon (Maimonides 1135-1204) who was wildly controversial when he lived and whose legacy has been profound. He lived in what’s now the south of Spain but was forced to move to Egypt and its environs by antisemites. At the end of the Middle Ages or in the Early Modern era (depending on how you define periods) an easier to read codification was written, first in 1563 by Joseph Caro (living in what is now Syria from 1488–1575, he was actually born in Toledo and thrown out along with all other Jews in 1492) and then annotated for Ashkenazi Jews by Moses Isserles (born in Krakow in 1530). I’ve used the English translation and it really is a codification of the complicated that makes much of the standard part of Jewish law accessible to the masses.

How the Talmud began to be read included more than those codifications. This is where things start to get funky. Also, my timeline is warped.

The Talmud as we know it is not simply what was written by 800, of material that was commonly used for Jewish law and education earlier than that. The Medieval book contained commentaries. The most important one is by one of my favourite rabbis of all time, Rashi (Shlomo Yitzchaki, or Solomon son of Isaac 1040-1105). He was trained in what is now Germany (and if he was born there, he may well have had a secular name as well as a Hebrew name), but most of the work that we know of was done in Normandy. This has a rather important implication for the return of Louis IX, so hold the thought: the most important commentary on the Oral Law was done by a Frenchman.

Rashi’s vineyard helped him earn the money to teach and to study and to write brilliant philosophical, legal and other stuff. He was a genius.

Why do I love Rashi? He gave me proof that young women wore blue eyeshadow to look sexy and how they carefully laced the sides of their dresses to also look sexy. He gives us evidence of hot water machinery and foot braziers and even paper clips. His answers to religious questions incorporated the everyday of his congregants and the general Jewish public. He taught his daughters and they played an important part in the transmission of Jewish learning during his life and after his death. Also, he liked a good pot roast.

Rashi wrote a commentary that was written as part of the frame around the Talmud when it became what we know know it as. His legacy-scholars, the Tosafists, also wrote commentary and that was also made part of the frame. To read the Talmud, then, is to read a chronicle of the thoughts of many major rabbis from the third century to the thirteenth century as a documentation of non-documented Judaism from earlier.

Now we’re back to Louis IX, who lived from about 1226 to 1270. Christianity changed throughout the Middle Ages. By the thirteenth century western Christianity had become very interesting indeed. It accepted Judaism, as I said earlier, within limits. There was much debate of the public sort and Louis decided (with the help of those difficult public debates) that the Talmud with all its commentaries transgressed those limits. It was material that Jews had developed since the time of Jesus and this was not permissible.

Twenty-five cartloads of these amazing books were burned. Twenty-five. Cartloads. Each volume had been written by hand and was worth, in modern terms, at least as much as a good EV.

None of this is my big revelation. My revelation is that I finally realise why Louis felt burning books was so imperative.

He didn’t want to destroy Jews. Unlike some other rulers at other times, Louis had a place for us in his theology. What he didn’t have a place for were culturally-developed, successful Jews who did not fit stereotypes. It’s as if Mr Not-Quite-Bright from next door can only accept Jews who are moneylenders or part of a secret cabal that controlled the world. When his Jewish next door neighbours admitted that he was a schoolteacher and she a lawyer, he could not cope and set fire to their shed.

This isn’t an insight into Louis IX. We already knew this about him. He wanted to world to fit his (occasionally generous but usually religious) world view. What has kept me up far, far past my sensible bedtime is that this means that there may have been more Jews in northern France than I thought and that they must have been culturally amazing. I knew this deep down, because scholars like Rashi don’t just appear out of nowhere and leave a vast legacy of learning and writing.

Late in life, Rashi saw some of those who went on the First Crusade murder many, many people he know. I think we underestimate how much hurt was done because we are so used to the world of Jews being torn apart and Jews being murdered. I suspect I need to visit my first area of specialisation and rethink the culture of Northern France. I did this for Germany recently and … I suspect that France was not a Christian country, but a country under Christian rule. Those books were written by people and studied by people and did not emerge from a vacuum. It was, I suspect, the fact that Jewish life was in an amazing stage of growth and learning that triggered Louis the Pious.

When I finish my current projects (this may take a year or so) I shall return to my intellectual homeland and analyse the evidence I thought I knew. Instead of saying, “There are no Jews in the chansons de geste, so there can’t have been many Jews” I shall look for evidence of growth and change and disruption and sudden discovery. I suspect there may be a novel in this, and if there is, I suspect it may contain fairies. I have Reasons.

Before I can explore those Reasons, though, I need to get my paleography books out and find out just how many people we’re talking about when we’re wondering about who copied those Talmuds and how different Hebrew manuscripts were (in terms of labour and time and money spent creating those manuscripts) were to the Latin and Old French manuscripts I know much more about. Look at the dates. Rashi died in 1105. The books were burned in 1242. I need to do some sums. And more. Much more.

I can’t even begin the research until I have finished all my current projects. This is why I am so kindly giving you my sleeplessness. I am sharing the pain of something I can’t even begin to work on at this moment. I’m a very kind person.

Over lunch this week, Madeleine Robins and I discussed a book we’ve both read more than once: Sinclair Lewis’s It Can’t Happen Here.

Over lunch this week, Madeleine Robins and I discussed a book we’ve both read more than once: Sinclair Lewis’s It Can’t Happen Here.

Back in 2016, I posted a series of blogs entitled In Troubled Times. Today it seems fitting to remind myself that I survived then and will survive now. These thoughts are from Monday, December 5, 2016.

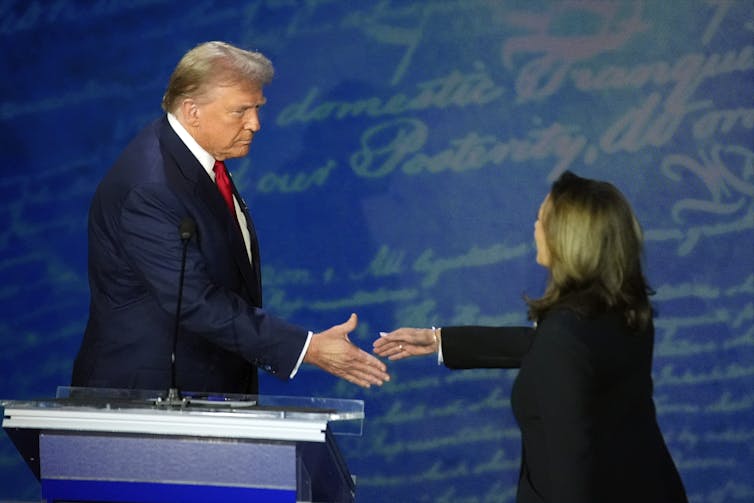

Back in 2016, I posted a series of blogs entitled In Troubled Times. Today it seems fitting to remind myself that I survived then and will survive now. These thoughts are from Monday, December 5, 2016. Historian Timothy Snyder keeps telling us “Do not obey in advance” even as more and more people appear to be leaping up to kiss the ring (or perhaps a part of the anatomy) of the grifter now apparently headed back to the White House in the ultimate triumph of the January 6 insurrection.

Historian Timothy Snyder keeps telling us “Do not obey in advance” even as more and more people appear to be leaping up to kiss the ring (or perhaps a part of the anatomy) of the grifter now apparently headed back to the White House in the ultimate triumph of the January 6 insurrection.