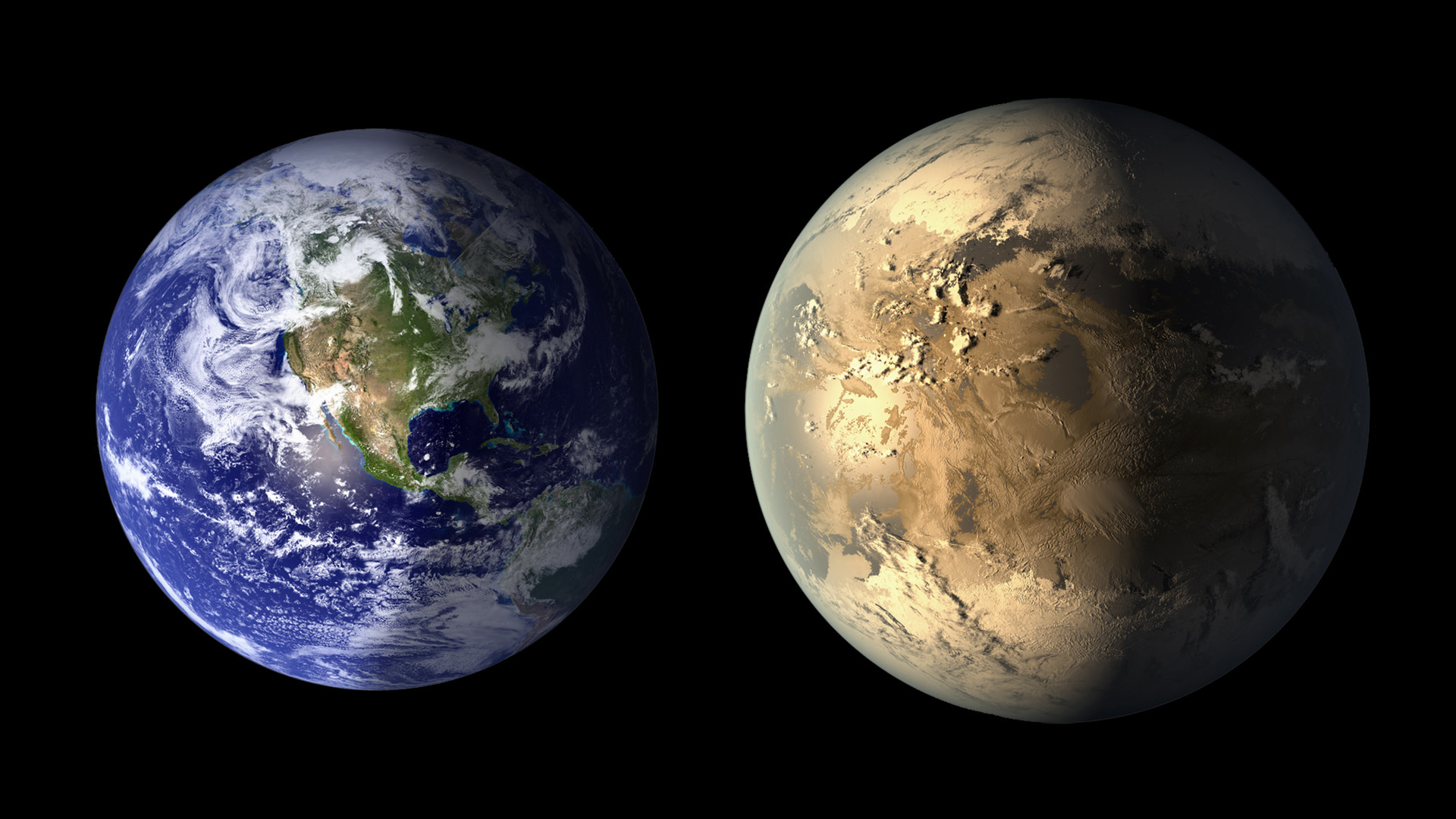

With thousands of known exoplanets and tens of thousands likely to be discovered in the coming decades, it could be only a matter of time before we discover a planet with life. The trick is proving it. So far the focus has been on observing the atmospheric composition of exoplanets, looking for molecular biosignatures that would indicate the presence of life. But this can be difficult since many of the molecules produced by life on Earth could also be produced by geologic processes. A new study argues that a better approach would be to compare the atmospheric composition of a potentially habitable world with those of other planets in the star system.

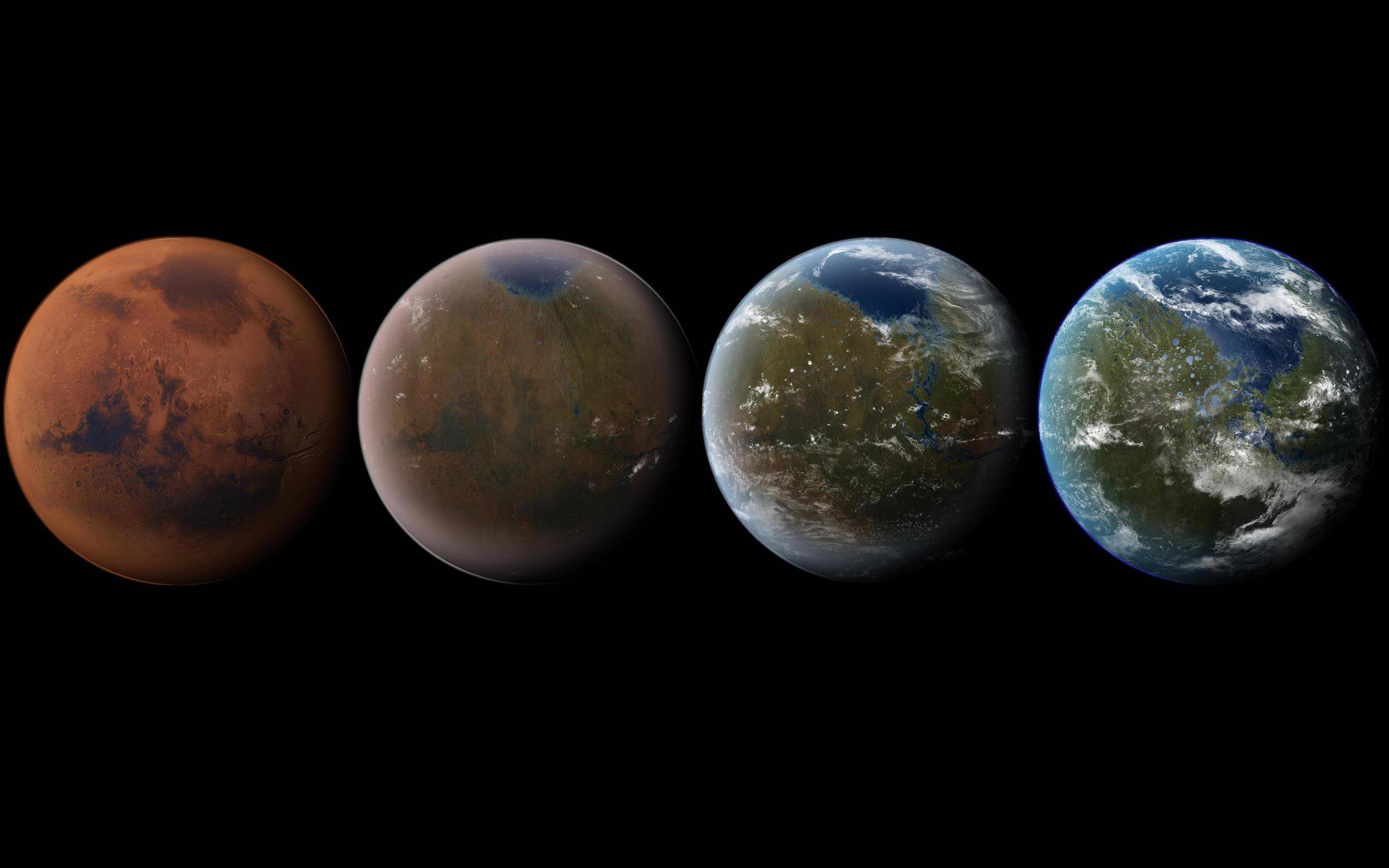

Since planets form within the debris disk of a young star, they will generally have similar compositions. Because of the migration of certain molecules such as water ice, the outer planets can have a slightly different composition than the inner planets, but overall their composition is similar. For this study, the team looked at the abundance of atmospheric carbon among worlds.

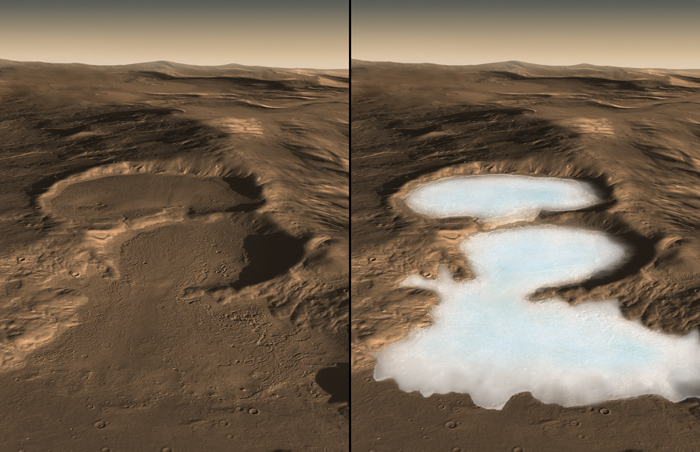

Carbon is not just a primary element for life on Earth, it also absorbs readily in water and can be bound geologically in rocks. So the idea is that if an exoplanet is in the potentially habitable zone of a star and has significantly less atmospheric carbon than similar worlds in its system, then that is a strong indicator of the presence of water and organic life. Take our solar system as an example. Earth, Venus, and Mars are all roughly in the habitable zone of the Sun, but both Venus and Mars have atmospheres comprised mostly of carbon dioxide. In contrast, Earth has an atmosphere of mostly nitrogen and oxygen, and only a fraction of a percent of carbon dioxide. Earth’s atmospheric carbon is so dramatically different from that of Venus and Mars that it stands out as a likely inhabited world.

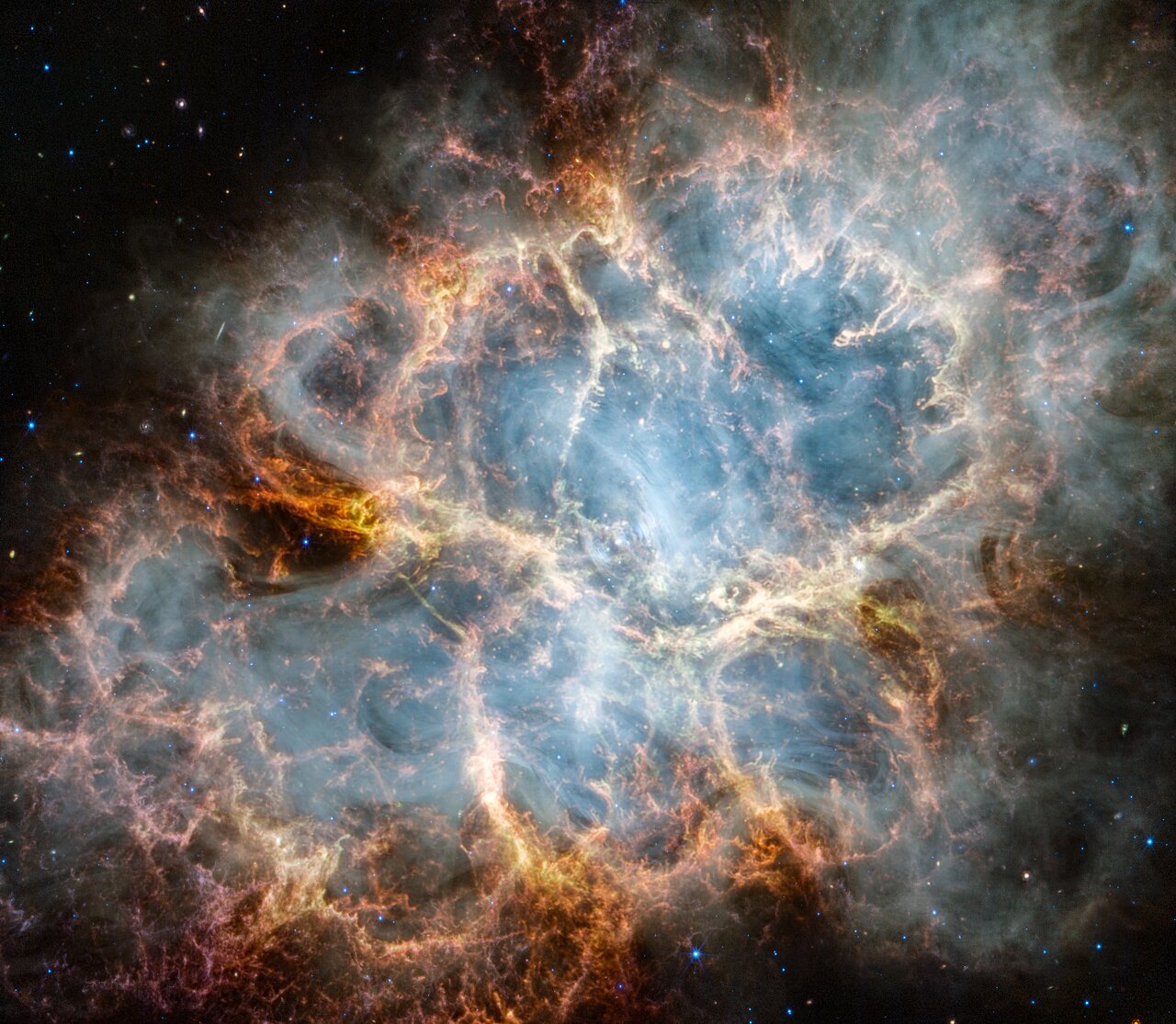

The Crab Reveals Its Secrets To JWSTThe Crab Nebula – otherwise known as the first object on Charles Messier’s list of non-cometary objects or M1 for short

It has been known that there is a pulsar at the core of the nebula, and it’s this pulsar that is the true remains of the progenitor star. When it went ‘supernova,’ the core collapsed to form the ultra-dense rotating object that, if you happen to be in the right place in space (hey, that rhymes), then you will see a pulse of radiation as it rotates. The infrared images from JWST reveal synchrotron emissions, which are a direct result of the rapidly rotating pulsar. As the pulsar rotates, the magnetic field accelerates particles in the nebula to astonishingly high speeds such that they emit synchrotron radiation. As a fabulously lucky quirk of nature, the radiation is particularly obvious in infrared, making it ideal for JWST.

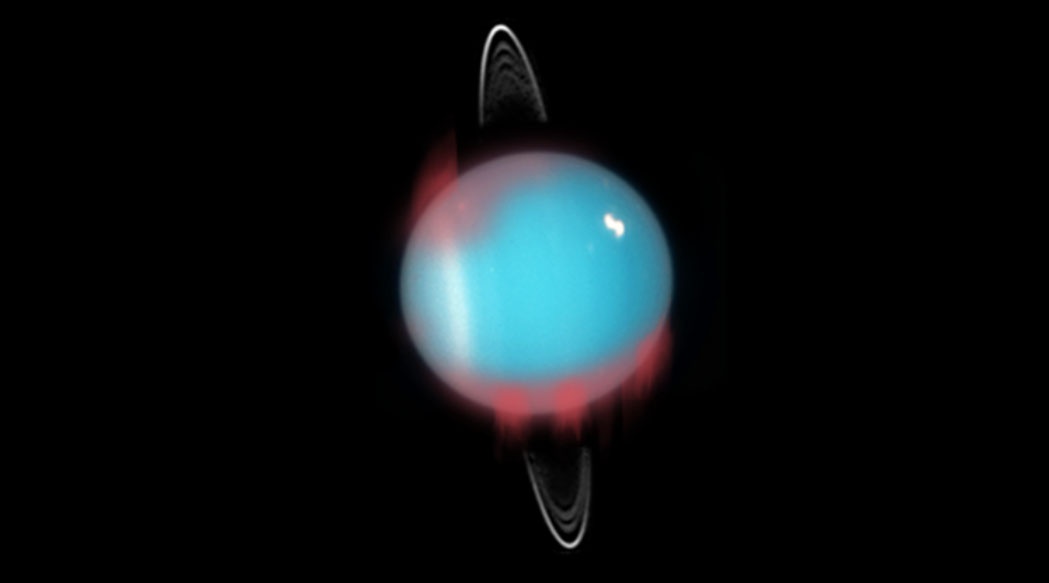

Uranus Has Infrared Auroras, Too

Auroras happen when charged particles in the solar wind and near-planet environment get trapped by a planet’s magnetic field. They funnel down to the atmosphere and collide with gas molecules. This happens on Earth and we see auroras over the north and south poles of our planet. They also happen at other planets. Astronomers detect them on the other giant planets, and a smaller version of them occurs on Mars. Venus probably doesn’t experience similar types of auroral displays, since it has no intrinsic magnetic field. However, it may experience something like them during particularly gusty solar wind events. At the outer planets, the gas mix is different in the atmospheres. That means their aurorae show up in ultraviolet and infrared wavelengths.

Uranus has an interesting magnetic field. It does not originate from the exact center of the planet. It’s also offset by 59 degrees from the rotation axis. That’s tipped 90 degrees from the plane of the solar system. This arrangement means that the Uranian magnetosphere is asymmetric and its field strengths vary depending on location. It connects with the solar wind once every Uranian day (which is 17 hours long). The planet does show some auroral activity, particularly around the poles and Hubble Space Telescope detected some in 2011

Three Planets Around this Sunlike Star are Doomed. Doomed!According to new research we can start writing the eulogy for four exoplanets around a Sun-like star about 57 light years away. But there’s no hurry; we have about one billion years before the star becomes a red giant and starts to destroy them.

The star is Rho Coronae Borealis, a yellow dwarf star like our Sun. It’s in the constellation Corona Borealis, and has almost the same mass, radius, and luminosity as the Sun. The difference is in their ages. The Sun is about five billion years old, but Rho CrB is twice that, which means its red giant phase is imminent, at least in astrophysical terms.

Post main sequence stellar evolution can result in dramatic, and occasionally traumatic, alterations to the planetary system architecture, such as tidal disruption of planets and engulfment by the host star,” Kane writes. Rho Coronae Borealis is both old and bright, making it “… a particularly interesting case of advanced main sequence evolution,” according to Kane. Not only because its similar to the Sun and easily observed, but also because it hosts four exoplanets.

Astronomers have found plenty of white dwarf stars surrounded by debris disks. Those disks are the remains of planets destroyed by the star as it evolved. But they’ve found one intact Jupiter-mass planet orbiting a white dwarf.

Are there more white dwarf planets? Can terrestrial, Earth-like planets exist around white dwarfs?

A white dwarf (WD) is the stellar remnant of a once much-larger main sequence star like our Sun. When a star in the same mass range as our Sun leaves the main sequence, it swells up and becomes a red giant. As the red giant ages and runs out of nuclear fuel, it sheds its outer layers as a planetary nebula, a shimmering veil of expanding ionized gas that everybody’s seen in Hubble images. After about 10,000 years, the planetary nebula dissipates, and all that’s left is a white dwarf, alone in the center of all that disappearing glory.

White dwarfs are extremely dense and massive, but only about as large as Earth. They’ve left their life of fusion behind, and emit only residual heat. But still, heat is heat, and white dwarfs can have habitable zones, though they’re very close.

Astronomers are pretty certain that most stars have planets. But those planets are in peril when they orbit a star that leaves the main sequence behind and becomes a red giant. That can wreak havoc on planets, consuming some of them and tearing others apart by tidal disruption. Some white dwarfs are surrounded by debris disks, and they can only be the remains of the star’s planets, ripped to pieces by the star during its red dwarf stage.

But in 2020 researchers announced the discovery of an intact planet among the debris disk in the habitable zone around the white dwarf WD1054-226. If there’s one, there are almost certainly others out there somewhere. Why haven’t we found them? And does the fact that the first one we’ve found is a Jupiter-mass planet mean the WD exoplanet population is dominated by them?

Old Data from Kepler Turns Up A System with Seven PlanetsNASA’s Kepler mission ended in 2018 after more than nine years of fruitful planet-hunting. The space telescope discovered thousands of planets, many of which bear its name. But it also generated an enormous amount of data that exoplanet scientists are still analyzing.

Kepler 385 is similar to the Sun but a little larger and hotter. It’s 10% larger and about 5% hotter. It’s one of a very small number of stars with more than six planets or planet candidates orbiting it.

The two innermost planets are both slightly larger than Earth. According to the new catalogue, they’re both probably rocky. They may even have atmospheres, though if they do, they’re very thin. The remaining five planets have radii about twice as large as Earth’s and likely have thick atmospheres.

Jupiter and Saturn, but Voyager 2 continued on to Uranus and Neptune. They’re both now outside the solar system, sending back data about the regions of space they’re exploring.

Jupiter and Saturn, but Voyager 2 continued on to Uranus and Neptune. They’re both now outside the solar system, sending back data about the regions of space they’re exploring.