Robert Freeman Wexler’s novel The Painting and the City was recently released in paperback by The Visible Spectrum and his collection Undiscovered Territories is now out in limited editions from PS Publishing.

Robert Freeman Wexler’s novel The Painting and the City was recently released in paperback by The Visible Spectrum and his collection Undiscovered Territories is now out in limited editions from PS Publishing.

Robert and I met at Clarion West in 1997 and have been friends ever since. It helped that we share a love of Texas music and also that we liked each other’s work from the beginning, despite the fact that we are very different writers.

So this will not be an arm’s length interview, but rather a chance to revel in the very different worlds that Robert can create. His is the kind of fantasy in which anything might happen.

NJM: Hi, Robert. Welcome to the Treehouse.

RFW: Hi Nancy. Thanks for taking the time to do this interview.

NJM: I’ve seen a lot of discussions by writers about magic systems of late. Some writers set up systems of magic as detailed and documented as those used to explain the science in hard science fiction. Others wing it a little more, but still have rules. But many of the fantastical things that happen in your stories don’t seem to fit into any rules of any kind. Why have you chosen to do that?

RFW: This isn’t something I’ve thought about at all, so I can’t say I’ve even made a choice. But I hope that my lack of rules doesn’t make everything feel random, unthought, arbitrary. In my writing, rules, if there are any, grow subconsciously, organically, for what fits the story. Things need to make sense, even if they weren’t created with textbookish thinking.

NJM: If I were going to describe your work, the word surreal would come into it. What surrealist works influence you?

RFW: Salvador Dalí, first, as in the first surrealist artist whose work I saw, because my mother gave me a book of his art when I was young. After Dalí, you could say pretty much everyone else. René Magritte, Max Ernst, Remedios Varo, Yves Tanguy, Victor Brauner, art and writings of Leonora Carrington. And those whose art I’ve seen but can’t remember their names. And others not necessarily surrealist but connected, like Joseph Cornell or Giorgio de Chirico. So, sure, all of them. However, Magritte especially, because I attempted to use his imagery in a lot of early stories.

NJM: I’ve always considered The Painting and the City as a love letter to New York City, though one mindful of the contradictions of its history and its difficulties. Was it intended that way? As someone who once lived in NYC, what are some other thoughts you have about the city?

contradictions of its history and its difficulties. Was it intended that way? As someone who once lived in NYC, what are some other thoughts you have about the city?

RFW: I didn’t set out to write the city a love letter, but I can see the novel giving you that sense. New York has always been in constant flux, yet maintains its sense of self. Not the public, generic self of the Big Apple or whatever, but as a city that’s an originator, incubator, etc. It’s a big messy place, beautiful and horrible. Ruined by too much money yet not all of it, not all the time. One reason is that it can’t sprawl like other cities, so change needs to conform to geography. Although I just read about a plan to extend the city into the harbor, past Battery Park.

Unlike, for example, Houston, where I grew up, which spreads like a bloated sewer with no sense of self. Or that’s the Houston I remember from growing up there. Maybe it’s different now. Houston has become one of or maybe the most culturally diverse city in the country, which is neat, and way different from when I lived there.

But back to NY. Unable to expand and annex the way other cities do, New York sprawls upward, leveling shorter buildings to build taller ones, usually condominiums for the continual and continually mysterious influx of young people with money. That destruction-construction bothers me, especially in what I consider to be my parts of town, Chinatown and the Lower East Side. I would rather those be preserved, especially Chinatown.

And speaking of rapid change to beloved cities, I recently read a book called Shark’s Fin and Sichuan Pepper—A Sweet-Sour Memoir of Eating in China, by Fuchsia Dunlop, which is in part a love letter to the city of Chengdu and Sichuan food. She went to Chengdu as a student in 1994. In the late ’90s, during China’s push to industrialization, she saw massive changes overcome the city.

In the mid-nineties, Chengdu was still a labyrinth of lanes, some of them bordered by grey brick walls punctuated by wooden gateways, others lined with two-storied dwellings built of wood and bamboo. (p. 38)

Later, in 2001:

…during the architectural reign of terror of city mayor Li Chuncheng (or Li Chaiqiang—‘Demolition Li’—as he was popularly known). Li was a man determined to make his mark on the era by demolishing the old city in its entirety, and replacing it with a modern grid of wide roads lined with concrete high-rises. Great swathes of Chengdu were cleared under his command, not only the more ramshackle dwellings, but opera theatres and grand courtyard houses…. (p. 41)

One week I would be cycling through a district of old wooden houses…the next, it was a pile of rubble, with a billboard depiction of some idealized apartment blocks overhead. (p. 110)

…It felt like a personal tragedy for me, to fall in love with a place that was vanishing so quickly. My culinary researches began as an attempt to document a living city; later, it became clear to me that, in many ways , I was writing an epitaph. (pp. 110-111)

This kind of change hasn’t happened to New York, yet. But I find the concept interesting, the idea of someone with the power to recreate a city without having to worry about those little people who live in it. And, so, I’ve used this power of destruction reconstruction for a fictional New York, in a middle grade novel that I finished last year. A man known as the Developer is in process of reforming New York in exactly that way.

I set The Painting and the City before 9/11 because that’s when I lived there. I had intended The Painting and the City to be a 9/11 novel that never mentions 9/11, but I must have failed, because no one noticed. Continue reading “Exploring the Undiscovered With Robert Freeman Wexler”…

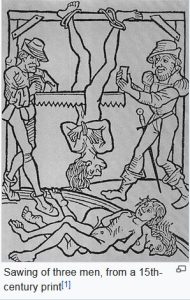

one character thinks it might be his fate, another reflects on it after seeing it take place. We tend to know about hanging, drawing and quartering. The drawing by the way was being drawn to the place of execution on a hurdle, not having the guts drawn out of the belly while still alive. So the victim was drawn through the streets, hanged and then his body cut into quarters. So really it should be drawn, hanged and quartered, in that order.

one character thinks it might be his fate, another reflects on it after seeing it take place. We tend to know about hanging, drawing and quartering. The drawing by the way was being drawn to the place of execution on a hurdle, not having the guts drawn out of the belly while still alive. So the victim was drawn through the streets, hanged and then his body cut into quarters. So really it should be drawn, hanged and quartered, in that order.

contradictions of its history and its difficulties. Was it intended that way? As someone who once lived in NYC, what are some other thoughts you have about the city?

contradictions of its history and its difficulties. Was it intended that way? As someone who once lived in NYC, what are some other thoughts you have about the city?