On 4 April 2010, BiblioBuffet published the beginning of a thought I had. I introduced many people to my library and, indeed, to my booklife. I am still surrounded by books. The piles grow and shrink and topple everywhere. The books in them demand to be talked about. Every Monday I will post about the loudest books. Sometimes it may be a short post, sometimes a longer. When my life gets tough (as it does) I may share an old piece of writing… but it will be about books.

To begin this blog series in style, let me begin with that post from 2010. An old post for the second last Monday of the old year. Next week I’ll find another old post of an entirely different kind, but still about books. Then the new year will begin. My furniture has changed, my life has changed, even my books have changed. When the year, too, changes, we will explore books together, week by week.

An introduction to my booklife

When I’m happy, I make lists. When I’m unhappy, I make different lists. I sit in my apartment, monopolise the big armchair, slide my writing desk into place, make sure the TV remote control is within reach, take a sip from my oversized mug of tea and then I’m ready. I produce list after list. I should go into business as a list-producing factory.

Right now, I feel like making a list, so that’s what I’m doing. Mostly, however, I’m making this list to introduce you to my books and their habitat (my apartment). They are central to my existence, they protect me against the outside world and line my walls to insulate against vile weather, and they’re going to appear in this column, so they have been drafted into duty as windows to my soul. Besides, if you didn’t get my books and a list, you would get a potted biography. A half-organised tour of a life in books is infinitely more interesting than a potted biography. (Even if it were boring, it would be a list of ten and lists of ten are wondrous things.)

1. Stacks of cookbooks

Cookbooks stack. In theory, they inhabit the shelves on either side of the television and the one behind the door, have colonised the second pantry shelf and a quarter of the wine cabinet. Despite their best colonial efforts, my cookbooks don’t fit in shelves. They tumble out of place when I can’t remember proportions, ingredients, taste or history then pile up interestingly until I can find a gap, any gap, in the overfull shelves. The stacks have no regard for language, though the cuisines that predate the founding of Australia do tend to ape dignity, while the homegrown community cookbooks look haphazard no matter where they are. Some of them are sticking out of a camel saddlebag right now: these look particularly random despite the fact they this is their current shelf (is there a rule against saddlebags holding books?).

Other peoples’ cookbooks stack. My cookbooks stack flamboyantly. They stack in shelves, on shelves and next to shelves. They hide other books and obscure everything from a reproduction of the Auchlinleck manuscript to a pile of French bandes-dessinées. My cookbooks are very presumptuous. Some are also attention-grabbers. The one drawing most attention to itself right now is Mrs Child’s The American Frugal Housewife, 1833 (a reproduction). Mrs Child’s ghost is obviously demanding I write about her book one day. Today, however, is not the day.

Today I started a new stack of books that demand attention and that want to be written about, and she’s right on the bottom of it. Immediately above it is a book that flirted with me. It’s a cookbook (with stories) by romance writers. With a pink cover. A very pink woman eating a chocolate éclair. And now I crave chocolate éclairs. I think I should move on from my cookbooks, quickly.

2. Other stacks.

We shall not discuss these. The most obvious of these contain review books and do not get talked about or even thought about until the time is right. They’re demanding children and need quality time. Besides, the visible books all sport zombies on the cover and one also has a law clerk wielding an axe.

3. Reference books!

It’s impossible to write about my reference books without copious exclamation marks (!!!!). I have a USB drive containing many thousands, which deserves one exclamation mark, at the least. This means that a good part of my reference library travels with me, everywhere. If I could only remember my netbook, then I could use them everywhere, too. I never forget to put a book in my handbag, but I often forget the computer.

The hardcore reference books are the ones I use. They’re on paper, too, and sit near my desk. They range from dictionaries to encyclopedias. I have a volume on love and sex in the Middle Ages, two on Medieval folklore and several on science fiction and fantasy. I also have at least half a dozen herbals and several manuals of etiquette.

I think my least used reference book (of the paper ones) must be the rules to card games. My most used one is a nineteenth century dictionary. My current favourite is a nineteenth century guide to pronunciation of the English language.

4. A stack unto itself is my copy of Kellogg’s The Ladies’ Guide, a rather beautiful old tome. It sits next to the skull box (which contains Perceval, who is disarticulated) and some handmade lace, a few arrowheads from Hot Springs, Arkansas, and on a segment of a 1930s wedding obi. Kellogg is preachy and needs keeping under control. Between the arrowheads and the skull, civilisation is maintained.

5. The corridor is a transit zone and contains no books. The laundry and the bathroom are also transit zones. They are officially boring.

6. The library.

The library is the room with the most books. The only books that stack in the library are the five hundred or so patiently waiting their turn for shelf space. It was the spare bedroom until my visitors rebelled against sleeping in the margins between bookshelves. Those visitors who enjoy sleeping on book-infested carpet announce to their friends “I slept in L-space last night.” L-space doesn’t fit neatly inside items 6-9, but that’s all the space I’m devoting to it.

7. Fiction

I can’t talk about my fiction in just one sub-heading in just one essay. Three walls of bookshelves stacked to the ceiling and without an inch of spare space are not summarised so lightly.

Also, Thomas Hardy and George Gissing are dignified. Robertson Davies thinks he is. I’m not sure they’d appreciate being discussed in too close proximity to some of the other writers populating my fiction shelves.

Also, how do I discuss Eleanor Farjeon and Ionesco and Alan Garner and Joan Aiken all in one breath?

8. Nonfiction

There are only two giant shelves of nonfiction. This isn’t because I don’t like nonfiction. It’s because I’m a cheat.

Nonfiction doesn’t include herbals or Judaica because both of those belong with my cookbooks. Non-fiction doesn’t include Arthuriana, because that belongs with my Medieval Arthurian collection which belongs (you guessed it) with my cookbooks.

Nonfiction doesn’t include any history before 1800. History before 1800 doesn’t belong with my cookbooks. It belongs in my bedroom where I can access it at any time and where no-one else can see things and say “Gillian, I’ll just borrow this.” My versions of the Pseudo-Turpin Chronicle are not part of my lending library and I shall defend them stoutly with my corn tooth sickle (which I keep near the cookbooks, of course, because those cookbooks need defending most).

Nonfiction is everything that’s not cookbooks, Arthuriana, Judaica, Medieval, Renaissance, womenstuff… this list is getting exhausting. It’s alphabeticised by author, which is the main thing. I should just call it “Everything else,” but “Nonfiction” makes it sound as if I know what I’m doing with those two enormous shelves.

9. There’s a shelf hidden in my sorting bookshelf (where I keep those books I haven’t yet put away, for whatever reason, but that really ought not be stacked) and it has books and etceteras by me. Over time, the etceteras diminish and the books multiply. It’s still a very small shelf hidden in a sea of books.

10. The heart of the addiction

Epic legends, romances, chronicles – all Medieval. Modern editions. Modern works about them. A complete Pepys. Kemble’s promptbooks (editions of Shakespeare). A few volumes of the nineteenth century Parliamentary records relating to the British colonies now called Australia. I could list volumes for ages and every one of them would be interesting. They’re select and special and wonderful and… most people would call the room they’re in a bedroom. It’s more books than bed, but there is indeed, a bed and I do sleep on it. I try not to sleep on books.

The trouble with writing a list of ten things is that the numbers run out before one has even begun. I haven’t even talked about the books I haven’t yet met. Some of them are clamouring to join my library, and yet they don’t fit in this list. I’ll do another list, one day, of books I yearn to meet. I’ve already done a list (on my blog) of the piles of books waiting to be read or written about or returned or dealt with severely. And I’m not going to get started on the many volumes on loan to friends (for my library is also a circulating library, payment in dark chocolate).

All these things are important. My life is books: books are my life. Right now, though, my booklife has probably outgrown my two-bedroom unit. I just need a few more rooms and my life would be perfectly ordered.

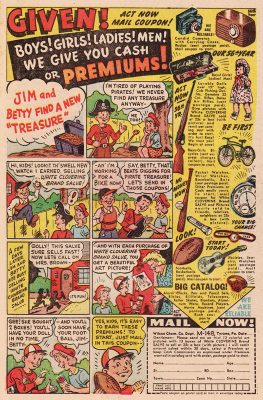

When I was a kid my brother and I collected comic books in great quantity. Collected and read and re-read and read the letters columns and the ads, entirely uncritically. Until I learned better.

When I was a kid my brother and I collected comic books in great quantity. Collected and read and re-read and read the letters columns and the ads, entirely uncritically. Until I learned better. Part of the reason my father wanted to own a Barn was so that he could experiment with it. Try things out. Like trapezes. Or gardens. Some of his experiments worked brilliantly; some of them, not so much. One of the more interesting ones was a floor treatment, if that’s what you could call it. Dad cut one-inch slices of 2x4s to use as tiles in the front entry room, what we called the tack room (in the days when the Barn was a working barn, it was where various animal-related gear had been stored). It was a good experiment, a sort of prototype. Dad had big plans, see. For the kitchen.

Part of the reason my father wanted to own a Barn was so that he could experiment with it. Try things out. Like trapezes. Or gardens. Some of his experiments worked brilliantly; some of them, not so much. One of the more interesting ones was a floor treatment, if that’s what you could call it. Dad cut one-inch slices of 2x4s to use as tiles in the front entry room, what we called the tack room (in the days when the Barn was a working barn, it was where various animal-related gear had been stored). It was a good experiment, a sort of prototype. Dad had big plans, see. For the kitchen.