Several kind (non-Jewish) friends tried to share Holocaust stuff with me last week. It was Holocaust Remembrance Day, after all. I’m afraid I hurt them by saying I wasn’t going to look, not at the article and not at the television. I didn’t need to be told that a large percentage of people who aren’t as bright or as human as they think don’t believe the Shoah existed. I don’t need to revisit the numbers nor the deaths. They are with me every day. My friends are (seriously, not sarcastically – and this has to be explained because, honestly, it sounds sarcastic) being kind. They’re including me in their own learning curve about one of the most difficult subjects around. My learning curve is, however, vastly different from theirs. I’ve been dealing with it all my life, because I’m Jewish and have always had non-Jewish friends.

I’ve been asked to explain it to people since I was seven. Be thankful I asked my father before showing my friend the picture in the book, because I didn’t have words but I did have pictures. The picture was of a pile of dead bodies on the day Auschwitz was liberated. I told Dad, “I was just going to explain about cousins.”

“Wait until she’s old enough,” I was told. I was old enough at six. Most of my friends took a few decades before reaching that moment. I was the only family member who learned things that early, if that’s any consolation. I needed to understand things, and so I’ve spent most of my life trying to understand the Shoah. I’ve done so much explaining over the years. I’ve had a responsibility to explain, because my family wasn’t hurt. If we had not left Europe, I could have been Anne Frank, I thought, when I was twelve.

Some years, I have discovered, I need a break from being the person who can share someone’s learning experience or who explains everything. This year is one of those years, because this year antisemitism is so much worse than it has been. The Shoah feels too close.

I’m one of the lucky ones, I used to say, because all of my grandparents were in Australia long before the murders began. My father’s mother was, in fact, born in Australia. I only lost the family of my European grandparents: this is a massive privilege. No relatives surviving in three cities and a country town is easier to handle, emotionally, when I had all my next-of-kin. Recently I’ve taken to handling my good fortune by talking about the one surviving member from the whole of the Bialystocker family that had not migrated to Australia by 1938. I’ll introduce you to him if you ask me, in conversation. Not in a blog post. Not yet.

I dealt with Yom Ha’Shoah this year by reading something that shows how different things can be when someone gives us permission to step outside the stereotypes. The War was different for those who were given choices other than being victims.

Previously, when people told me, “Your relatives should’ve fought,” I’ve told them about my great-uncle who lived and the one who died, and about my cousin, all of whom were part of the army and air force and… Australian. Australia fought Germany in World War II and quite a few of my relatives were part of those battles. I don’t want to talk about Les or Uncle Sol or even Uncle Max this year, either. Their choices help me personally deal with those who inform me that Jews are meant to die and never try to help themselves or others are part of the problem. They don’t know my family, Jewishness, or any history. People who talk about ever-victims are themselves part of the problem.

There’s a book being talked about right now in the Melbourne Jewish community. My mother’s best friend read it and told her, “You must!” My mother was reading it when I rang and said, “I can’t put this down. Can we talk later?” When she’d finished I got the name of it and the author and I’m nearly finished.

It’s not a happy book. It doesn’t hide the horrors of war. It is, however, a powerful volume. It shows that all the deniers are denying even more than they think. Not only did Jews fight the Axis Powers (as we know because my relatives were part of those battles) but some of them were… extraordinary. And of those extraordinary people, some tried very hard to create outcomes (on the very rare occasions when it was possible) where fewer people died.

While their families had been murdered or were being murdered in death camps, these men fought back. It was a British thing…

The book is X Troop: The Secret Jewish Commandos who helped defeat the Nazis. Not all of X-Troop was Jewish. Some members were defined as Jewish by the Nazis, but were actually Christian. The single rampant atheist described was, of course, Jewish – it’s much harder to be Christian and to be an atheist.

I didn’t want to revisit the Shoah last week. People telling me about it to match their discoveries is uncomfortable. It reminds me that this is part of the present, right now. I may really hate war stories, but right now, this war story gives me permission to keep fighting prejudice. That permission comes from such an extraordinary quarter.

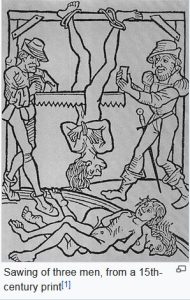

one character thinks it might be his fate, another reflects on it after seeing it take place. We tend to know about hanging, drawing and quartering. The drawing by the way was being drawn to the place of execution on a hurdle, not having the guts drawn out of the belly while still alive. So the victim was drawn through the streets, hanged and then his body cut into quarters. So really it should be drawn, hanged and quartered, in that order.

one character thinks it might be his fate, another reflects on it after seeing it take place. We tend to know about hanging, drawing and quartering. The drawing by the way was being drawn to the place of execution on a hurdle, not having the guts drawn out of the belly while still alive. So the victim was drawn through the streets, hanged and then his body cut into quarters. So really it should be drawn, hanged and quartered, in that order. s 2021 drew to a close I realized that I had fallen into a scam I hadn’t heard of: befriending a person on social media and then inducing them to set up a GoFundMe for a medical emergency. Fortunately, I came to my senses before I sent any money from that campaign. Until then, it had never occurred to me that I had been manipulated over a year and a half. As embarrassing as the experience was for me, I’m going public in the interests of educating others.

s 2021 drew to a close I realized that I had fallen into a scam I hadn’t heard of: befriending a person on social media and then inducing them to set up a GoFundMe for a medical emergency. Fortunately, I came to my senses before I sent any money from that campaign. Until then, it had never occurred to me that I had been manipulated over a year and a half. As embarrassing as the experience was for me, I’m going public in the interests of educating others.

contradictions of its history and its difficulties. Was it intended that way? As someone who once lived in NYC, what are some other thoughts you have about the city?

contradictions of its history and its difficulties. Was it intended that way? As someone who once lived in NYC, what are some other thoughts you have about the city? One of these things is not like the other.

One of these things is not like the other.