In honor of Banned Books week, I offer this memory of my daughter’s stand against book burning.

It would be difficult to find a neighborhood more concentrated with left-leaning intelligentsia than the Upper West Side of Manhattan. Which is not to say there are not conservatives, curmudgeons, and random people who think the world is going to hell in a handbag, but the traditional Person On The Street on the Upper West Side is likely, at the very least, to be four-square for the First Amendment.

Which is why my daughter burning a book on the sidewalk occasioned considerable outrage.

It was a perfectly gorgeous Saturday in spring; Julie, age 11 and at the tail end of 6th grade, had to do a multi-media report on a book of her choice, and the book of her choice was Ray Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 451. She had discussed the project with her teacher, and decided to do a three dimensional collage representing the pile of books that are burned in the book; ringed round the pile would be text from the novel (one of the major discussions was which quote; the book is chock full of good lines).

If there’s one thing we have around the house, it’s books. Some of them so old and tattered they would probably go up in smoke at an incendiary glance; others still young and green enough that a match would be required. And I’m afraid I feel rather proprietary–nearly maternal–about all of them. It took us several hours to find a grocery-bag full of books that could be sacrificed in the name of education, and I insisted, for safety’s sake, that this all be done outside on the sidewalk, where nothing much could catch fire. A book-burning kit was added to the bag: matches, oven mitts, a bucket (to be filled with water just before we went downstairs), a couple of tired old dish towels which would be sacrificed if necessary to smothering flames. In my head I had moved beyond issues of censorship and was thinking of getting my kids through this alive.

Saturday morning Julie and her little sister and I went downstairs and found a nice clear patch of sidewalk on our quiet side street, and set up for business. I supervised and distracted Becca (who was six, and to whom this was Just Another Inexplicable Thing Her Sister Did) while Julie went to work.

The first book burned too fast. Kid didn’t want a pile of ashes; she wanted books in various stages of char. This was how we decided that old, worn paperbacks were a bad idea. She took up a book of actuarial tables and had better luck with that, although working out the routine of lighting the page, blocking the breeze, pulling on the oven mitt, and putting out the flame when just the right amount of book had been burnt, took a little work. About the time the third book had been lit, an elderly couple came down the street, moving urgently. The man was practically waving his cane. The woman yelled: “WHAT ARE YOU DOING!”

Julie, to her credit, finished putting out the book before she turned around. “It’s for a class project,” she said.

“WHAT KIND OF SCHOOL ASSIGNS YOU TO BURN BOOKS?” (I was not sure if the woman was upset or deaf or both, but she was very loud.) “DON’T YOU KNOW WHO BURNED BOOKS?”

For a moment Julie looked a bit confused; in her mind at that moment, the answer would have been Montag, the “fireman” from Fahrenheit 451. “My school didn’t assign me to burn books; I’m doing an art project about a book about a man who–”

“BURNING BOOKS IS A TERRIBLE THING TO DO!”

“I know! That’s what the book is about.”

“WHAT BOOK IS THIS?”

Fortunately, we’d brought her copy of Fahrenheit 451 downstairs with us. Julie took off the oven mitt and showed the book. The woman reached for it, but the old man, whose caterpillar-like eyebrows had been working up and down with alarm, suddenly looked enlightened.

“Ahh,” he said. He turned to his companion. “She’s making art.”

“SHE’S BURNING BOOKS!”

He nodded. “I’ve read that book. It’s says that burning books is a terrible thing. She’s making art to show that.” He smiled at Julie. “Go ahead, sweetheart.” And he looped his arm through his companion’s and continued onward toward Amsterdam Avenue.

They weren’t the only ones to comment negatively on Julie’s project. By the time she had crisped the seven or eight books she required, four or five more people had come by and viewed with alarm. Each time she got a little better at explaining what she was doing, leading with “I’m doing an art project to demonstrate that burning books is bad.” She got into some interesting discussions. By the end of the hour or so it took her to get done, she was exhausted and a little annoyed at having had to explain what she was doing over and over again. From their accents, I think that the first couple were from somewhere in Eastern Europe, and likely immigrants from a formerly Communist country. The others who stopped were old and young, black and white. All were at least dismayed by what they saw happening. The protest I liked best came from a little kid who was out with his dad. “Don’t you like books?”

“I love them so much I don’t want anyone to do this. Ever. Plus, it’s for school.”

The little boy nodded and they went on. They’ll ask you to do anything if it’s for school.

Month: October 2025

How to Avoid Gillian at Octocon this weekend

Octocon is the Irish National Science Fiction Convention, and I’m on panels and giving a talk, online. I take seriously the fact that some people love all the things, but without Gillian. I used to joke about it with a “How to Avoid Me” guide. I decided to make things easier for antisemites by reintroducing these guides when I have time. Today I have time. (It’s either this or housework.) Here is that guide: happy Gillian-avoidance.

I’m giving Irish time and Australian time, thanks to the Octocon website, which translated everything for me. The easiest way of avoiding me is, of course, to strictly follow the Australian time and go to bed early. You can dream beautiful dreams instead of listening, say, to a talk on mostly-Medieval tricksters. Or, if you’re lucky enough to be in Dublin, go to the face to face versions of the panels.

Let’s start with tricksters. Do not be online or in the room streaming the online on Saturday 11 October at 11:30 IST or 21:30 GMT+11 (UTC+11 for those who GMT mystifies). You’ll be avoiding a talk and conversation on “Not the Usual Tricksters: Starting with the Middle Ages.” You will very happily miss hearing me snark about Robin Hood and talk about the origin stories that led to his trickster element. I may be polite about Renart (the Old French version) and Merlin (the Geeoffrey of Monmouth version). I will wax ecstatic about Ashmodai and his curious feet.

The conversation will all of us chatting about the tricksters of Western Europe. This conversation will be is less Commedia dell’Arte and more pop fantasy and folklore and regional traditions from the Middle Ages on. At this precise moment, I’m thinking about Evangeline Walton and Alan Garner and their stories about Welsh stories, but that’s this moment. Later today I plan to obsess (again) about Eustace.

The discussion bit will be open to most tales and most modern versions of tales. If people want to talk about Loki and other deities, we’ll save them until the end, because they get heaps of time in many conversations and Fulke Fitz Warin and Eustace the Monk do not. In my dreams someone informs us all about the Irish equivalents of both Eustace and Merlin.

Just this once, those tricksters who have historical evidence for their actual existence will be more important than those who are associated with building (Stonehenge and the First Temple come to mind) and anyone who existence only in literature (Renart) will be lesser players.

Why have I given you such a description? So that you can look up everything at your leisure and avoid me, of course.

Saturday, 13:00 IST or 23:00 GMT+11.

This is a classic What If… panel. Unfortunately for you, it has excellent panellists and one of the best moderators. I suggest watching online and turning the sound off when I’m talking.

Sunday 12 October 2025 at 10:00 IST or 20:00 GMT+11 is a Star Trek panel. Again, it has really good panellists (apart from me), but muting me twice would be boring for you. I suggest instead that you sing Star Trek themes whenever I speak. Or do your own version of the Charlie song from season one of the Original series. This way you avoid me, but get your Star Trek discussion… and it’s going to be a good one. Also, it turns the panel into a personal musical. If you feel the need to dance to the music, I won’t tell anyone.

Sunday at 11:30 IST or 21:30 GMT+11 is Historical Myths and How to (Not) Use Them. It’s online only, but… best avoid me and not the panel. After all, Jean Bürlesk is moderator and, unfortunately for you, the rest of the panel is also excellent.

This time I don’t suggest that you mute or sing. I suggest a drinking game. A slow, comforting half glass of something nice whenever I speak, a sip for every mention of a favourite historical myth, and a whole glass slugged down in a great hurry whenever the equivalent of an onstage costume change at Eurovision occurs. By the end of the panel you will have enjoyed a wonderful discussion on Historical Myths and also have an entirely sound understanding of why Australians love Eurovision so very much. (Just so’s you know, spellcheck wants to me change ‘Eurovision’ to ‘Neurosis.’)

And that’s it! That’s how to avoid Gillian while still enjoying every moment of Octocon.

PS If you’re avoiding me seriously and don’t even want to see my face, I suggest a moveable sticky patch to go on your computer screen. My favourite would be one with a koala and I can provide a picture for this, but stick figures are nicely universal and even easier. I do not recommend using super-glue.

Thinking About Old Age

I was reading an interview with Richard Osman (find it here in either video or a transcript), who has written a series of mysteries called the Thursday Murder Club about people over 80 living in a retirement community and solving mysteries.

The books are read worldwide, translated into a number of languages. In talking about how societies treat their elders – and assuming that in the UK and the US we treat them badly – he said this:

But in Mediterranean countries, in Arabic countries, in China, elders are traditionally revered. Except every time I go to one of those places, people say, “Oh no, we’re exactly the same. We treat older people terribly.” And I’ll say, “No, you don’t, not really.” And they insist, “Yes, honestly, that’s why we love these books.”

And that resonated with me, because I know there are segments in our culture which supposedly revere elders and yet as someone who technically qualifies for elderhood, when I see the way those elders are treated, I find it condescending.

I like the idea of a book that treats so-called elders like people, so I put the first one on hold at my library.

But I have to say, I don’t want to live in a retirement village. I want to live around people of all ages.

Michelle Cottle, who did the interview, said living in a retirement village would be kind of like being back in college except without having to go to class. But having spent time visiting people living in such places, I don’t find that true. Part of that might be that as much as we complained about it, going to class was a major part of going to college and generated a lot of the ideas that made for good conversations with our friends.

I would like to live in community that had some of the aspects of college – my six weeks at Clarion West, living in a dorm with my fellow students, going to class, barely sleeping, were a high point in my life. But the students in our group ranged from their early twenties to their mid-fifties.

So I’m not planning to move into a retirement village or similar facility for old folks, at least not now. My partner and I are part of East Bay Permanent Real Estate Cooperative and we are trying to organize a multifamily co-op apartment building as part of that, one that would include a diverse group of people.

But there is another issue here, one I wrestle with. What if I develop a condition such as dementia or another severe illness or disability and need the kind of full-time care one gets in assisted living or nursing homes? I do not want my partner, assuming he is still able to do so, to spend all his time caring for my needs, and even though I’m putting money aside for my care in the future, I doubt I will have enough for 24-hour live-in aides. Continue reading “Thinking About Old Age”…

Reprint: Fighting Book Bans

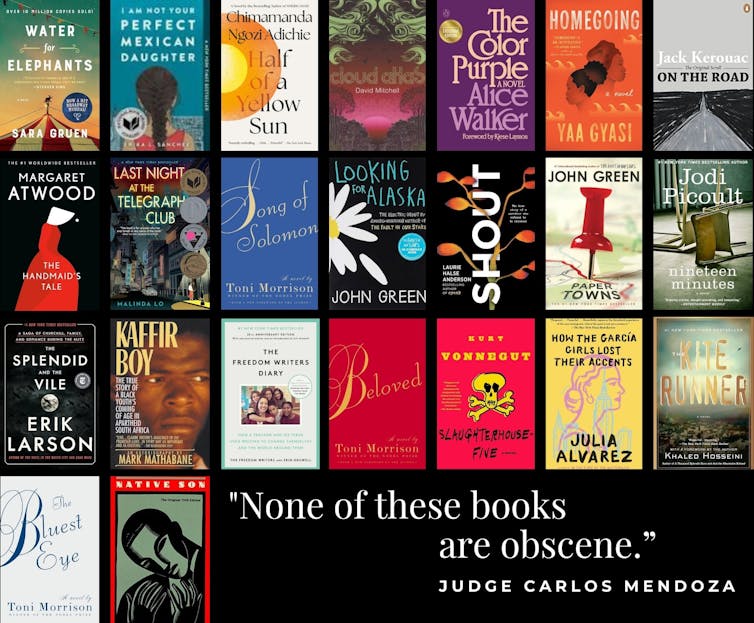

Federal judge overturns part of Florida’s book ban law, drawing on nearly 100 years of precedent protecting First Amendment access to ideas

Trish233/iStock via Getty Images

James B. Blasingame, Arizona State University

When a junior at an Orange County public high school in Florida visited the school library to check out a copy of “On the Road” by Jack Kerouac, it wasn’t in its Dewey decimal system-assigned location.

It turns out the title had been removed from the library’s shelves because of a complaint, and in compliance with Florida House Bill 1069, it had been removed from the library indefinitely. Kerouac’s quintessential chronicle of the Beat Generation in the 1950s, along with hundreds of other titles, was not available for students to read.

Gov. Ron DeSantis signed the bill into law in July 2023. Under this law, if a parent or community member objected to a book on the grounds that it was obscene or pornographic, the school had to remove that title from the curriculum within five days and hold a public hearing with a special magistrate appointed by the state.

On Aug. 13, 2025, Judge Carlos Mendoza of the U.S. Middle District of Florida ruled in Penguin Random House v. Gibson that parts of Florida HB 1069 are unconstitutional and violate students’ First Amendment right of free access to ideas.

The plaintiffs who filed the suit included the five largest trade book publishing houses, a group of award-winning authors, the Authors Guild, which is a labor union for published professional authors with over 15,000 members, and the parents of a group of Florida students.

Though the state filed an appeal on Sept. 11, 2025, this is an important ruling on censorship in a time when many states are passing or debating similar laws.

I’ve spent the past 26 years training English language arts teachers at Arizona State University, and 24 years before that teaching high school English. I understand the importance of Mendoza’s ruling for keeping books in classrooms and school libraries. In my experience, every few years the books teachers have chosen to teach come under attack. I’ve tried to learn as much as I can about the history of censorship in this country and pass it to my students, in order to prepare them for what may lie ahead in their careers as English teachers.

Legal precedent

The August 2025 ruling is in keeping with legal precedent around censorship. Over the years, U.S. courts have established that obscenity can be a legitimate cause for removing a book from the public sphere, but only under limited circumstances.

In the 1933 case of United States v. One Book Called Ulysses, Judge John Munro Woolsey declared that James Joyce’s classic novel was not obscene, contradicting a lower court ruling. Woolsey emphasized that works must be considered as a whole, rather than judged by “selected excerpts,” and that reviewers should apply contemporary national standards and think about the effect on the average person.

In 1957, the Supreme Court further clarified First Amendment protections in Roth v. United States by rejecting the argument that obscenity lacks redeeming social importance. In this case, the court defined obscenity as material that, taken as a whole, appeals to a prurient – that is, lascivious – interest in sex in average readers.

The Supreme Court’s 1973 Miller v. California decision created the eponymous Miller test for jurors in obscenity cases. This test incorporates language from the Ulysses and Roth rulings, asking jurors to consider whether the average person, looking at the work as a whole and applying the contemporary standards in their community, would find it lascivious. It also adds the consideration of whether the material in question is of “serious literary, artistic, political, or scientific value” when deciding whether it is obscene.

Another decision that is particularly relevant for teachers and school librarians is 1982’s Island Trees School District v. Pico, a case brought by students against their school board. The Supreme Court ruled that removing books from a school library or curriculum is a violation of the First Amendment if it is an attempt to suppress ideas. Free access to ideas in books, the court wrote, is sacrosanct: “If there is any fixed star in our constitutional constellation, it is that no official, high or petty, can prescribe what shall be orthodox in politics, nationalism, religion or other matters of opinion.”

Illustration by The Conversation

What this ruling clarifies

In his ruling in August 2025, Mendoza pointed out that many of the removed books are classics with no sexual content at all. This was made possible in part by the formulation of HB 1069. The law allows anyone from the community to challenge a book simply by filling out a form, at which point the school is mandated to remove that book within five days. In order to put a book back in circulation, however, the law requires a hearing to be held by the state’s appointed magistrate, and there is no specified deadline by which this hearing must take place.

Mendoza did not strike down the parts of HB 1069 that require school districts to follow a state policy for challenging books. In line with precedent, he also left in place challenges for obscenity using the Miller test and with reference to age-appropriateness for mature content.

The Florida Department of Education argued that HB 1069 is protected by Florida’s First Amendment right of government speech, a legal theory that the government has the right to prevent any opposing views to its own in schools or any government platform. Mendoza questioned this argument, suggesting that “slapping the label of government speech on book removals only serves to stifle the disfavored viewpoints.”

What this means for schools, in Florida and across the US

In the wake of Mendoza’s decision, Florida schools are unlikely to pull more books from the shelves, but they are also unlikely to immediately return them. Some school librarians have said that they are awaiting the outcome of the appeal before taking action.

States with similar laws on the books or in the works will also be watching the appeal.

Some of these laws in other states have also been challenged, with mixed outcomes. The U.S. Court of Appeals for the 5th Circuit already struck down Texas’ appeal of a ruling against Texas House Bill 900. And parts of an Iowa bill currently are being challenged in court.

But the NAACP’s lawsuit against South Carolina Regulation 43-170 was dismissed On Sept. 8, 2025. And Utah’s House Bill 29 has not yet faced a challenge in court, though it could be affected by the outcomes of these lawsuits in other states.![]()

James B. Blasingame, Professor of English, Arizona State University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.