Part of the reason my father wanted to own a Barn was so that he could experiment with it. Try things out. Like trapezes. Or gardens. Some of his experiments worked brilliantly; some of them, not so much. One of the more interesting ones was a floor treatment, if that’s what you could call it. Dad cut one-inch slices of 2x4s to use as tiles in the front entry room, what we called the tack room (in the days when the Barn was a working barn, it was where various animal-related gear had been stored). It was a good experiment, a sort of prototype. Dad had big plans, see. For the kitchen. Continue reading “Raised in a Barn: Blocks”…

Part of the reason my father wanted to own a Barn was so that he could experiment with it. Try things out. Like trapezes. Or gardens. Some of his experiments worked brilliantly; some of them, not so much. One of the more interesting ones was a floor treatment, if that’s what you could call it. Dad cut one-inch slices of 2x4s to use as tiles in the front entry room, what we called the tack room (in the days when the Barn was a working barn, it was where various animal-related gear had been stored). It was a good experiment, a sort of prototype. Dad had big plans, see. For the kitchen. Continue reading “Raised in a Barn: Blocks”…

Category: memoir

Difficult thoughts

Today’s book is a slow read, an absorbing one, and occasionally a very difficult one. It’s Polin, volume 22. Polin is a series of studies of Jewish history from a particular region. Polin 22 looks at social and cultural boundaries, mainly from the fifteenth to the seventeenth century. I’m taking a break from it because reading about the blood libel sucks. It always does. If my life were easier I’d not have to even think about it, but I can’t consider space and boundaries without considering those where there is intentional transgression.

Imagine someone making up a nasty lie. Imagine people being killed over it. Other people say “It’s a nasty lie.” People who support those who invented the lie in the first place don’t listen to the proof of it being a lie, but add torture to the questions posed to prove the victims have done the thing they actually didn’t do. The question in this chapter, I suspect, is whether the innocent people who are being blamed for this thing they didn’t do die from the torture or from the punishment.

I’m reading it to understand how the trial could even take place and how it operates. Is there even a modicum of fairness or justice? None. Not a skerrick. This is why I need to understand the trial itself. This is the chapter I need a break from.

The thing that stopped me in my tracks was the way questioning was done, before any torture. The subject was sprinkled with Christian holy water and forced to wear Christian religious items and made to eat some blessed salt and to say a Psalm. This was to defeat any Jewish lies he might tell. All the alleged child-killer (who was guilty only of being Jewish, and who murdered no-one) did was repeat the same simple truth: there was no requirement in Judaism to drink the blood of children, and it was something that no Jew would ever do. Over and over again he was forced to explain this and over and over again it was disbelieved. I’ve seen reports from blood libel trials where the Jew was blamed even when the child appeared, perfectly alive.

The whole blood libel was an invention and still is, today. When I was accused of it in primary school and of eating unleavened bread that contained the blood of newborn Christian children, I brought a whole box of matzah to school, and made the accusers read the ingredients on the box. The ingredients were water, flour and salt. I was told I was a liar, but other children were there and they passed the box around and everyone read the ingredients aloud. Primary school children believe in the printed word and someone (not one of the accusers) took some of the matzah out of the box, ate it, and we began to talk about its flavour. That particular episode was finished for that moment. My trial was very light.

The chapter brought back that memory. There was no way out for the three on trial in this case. Innocence was irrelevant, but likewise so was the concept of evidence.

At first I kept reading, despite the gut punch because I found a piece of evidence I hadn’t seen before (I wasn’t looking for it, to be honest) and I stopped to think. I wondered… how much of the nineteenth century “Keep vampires away” tricks began as “Keep Jews away.” I’m not sure I want to find out.

I have to read it, because it’s telling me important things about what happens when Jews are victimised at a time and place when things were pretty good, compared with other times and places. I’ll get through it and then take a deep breath and, from the moment the next chapter begins, I’ll be less full of misery. Something deep inside me hurts, every time I read a trial record or a description of one where everything is set up to make the innocent look guilty.

The next chapter is by one of my favourite scholars. I’ve never met her, but I read anything I can get hold of by her. I can’t get hold of much, being in the wrong corner of a far-flung globe, but… I want to skip straight to the Carlebach chapter on a chronograph. I want to skip seeing people hurt and enjoy contemplating time and space.

I’m going to return to reading and I’m going to finish the chapter. That’s the fastest way of not carrying the weight of history on my shoulders.

Raised in a Barn: When Cracks Become Visible

When you’re a kid you imagine that all the things your parents do are–if not correct–at least…thought out. Grown-up. Sensible. When you become an adult you realize that sometimes grown-ups are making it all up and that sometimes the improv veers into the realm of the inadvisable.

My mother was a beautiful woman, smart and warm and funny. She was also a woman who could raise anxiety to an art form, which made it all the more bewildering on those occasions when her sense of the absurd outpaced her anxiety. She was not an “anything for a laugh” kind of person, but sometimes…

Like the time she aimed at a police car with a toy gun.

Continue reading “Raised in a Barn: When Cracks Become Visible”…

Books: a new series for a new year

On 4 April 2010, BiblioBuffet published the beginning of a thought I had. I introduced many people to my library and, indeed, to my booklife. I am still surrounded by books. The piles grow and shrink and topple everywhere. The books in them demand to be talked about. Every Monday I will post about the loudest books. Sometimes it may be a short post, sometimes a longer. When my life gets tough (as it does) I may share an old piece of writing… but it will be about books.

To begin this blog series in style, let me begin with that post from 2010. An old post for the second last Monday of the old year. Next week I’ll find another old post of an entirely different kind, but still about books. Then the new year will begin. My furniture has changed, my life has changed, even my books have changed. When the year, too, changes, we will explore books together, week by week.

An introduction to my booklife

When I’m happy, I make lists. When I’m unhappy, I make different lists. I sit in my apartment, monopolise the big armchair, slide my writing desk into place, make sure the TV remote control is within reach, take a sip from my oversized mug of tea and then I’m ready. I produce list after list. I should go into business as a list-producing factory.

Right now, I feel like making a list, so that’s what I’m doing. Mostly, however, I’m making this list to introduce you to my books and their habitat (my apartment). They are central to my existence, they protect me against the outside world and line my walls to insulate against vile weather, and they’re going to appear in this column, so they have been drafted into duty as windows to my soul. Besides, if you didn’t get my books and a list, you would get a potted biography. A half-organised tour of a life in books is infinitely more interesting than a potted biography. (Even if it were boring, it would be a list of ten and lists of ten are wondrous things.)

1. Stacks of cookbooks

Cookbooks stack. In theory, they inhabit the shelves on either side of the television and the one behind the door, have colonised the second pantry shelf and a quarter of the wine cabinet. Despite their best colonial efforts, my cookbooks don’t fit in shelves. They tumble out of place when I can’t remember proportions, ingredients, taste or history then pile up interestingly until I can find a gap, any gap, in the overfull shelves. The stacks have no regard for language, though the cuisines that predate the founding of Australia do tend to ape dignity, while the homegrown community cookbooks look haphazard no matter where they are. Some of them are sticking out of a camel saddlebag right now: these look particularly random despite the fact they this is their current shelf (is there a rule against saddlebags holding books?).

Other peoples’ cookbooks stack. My cookbooks stack flamboyantly. They stack in shelves, on shelves and next to shelves. They hide other books and obscure everything from a reproduction of the Auchlinleck manuscript to a pile of French bandes-dessinées. My cookbooks are very presumptuous. Some are also attention-grabbers. The one drawing most attention to itself right now is Mrs Child’s The American Frugal Housewife, 1833 (a reproduction). Mrs Child’s ghost is obviously demanding I write about her book one day. Today, however, is not the day.

Today I started a new stack of books that demand attention and that want to be written about, and she’s right on the bottom of it. Immediately above it is a book that flirted with me. It’s a cookbook (with stories) by romance writers. With a pink cover. A very pink woman eating a chocolate éclair. And now I crave chocolate éclairs. I think I should move on from my cookbooks, quickly.

2. Other stacks.

We shall not discuss these. The most obvious of these contain review books and do not get talked about or even thought about until the time is right. They’re demanding children and need quality time. Besides, the visible books all sport zombies on the cover and one also has a law clerk wielding an axe.

3. Reference books!

It’s impossible to write about my reference books without copious exclamation marks (!!!!). I have a USB drive containing many thousands, which deserves one exclamation mark, at the least. This means that a good part of my reference library travels with me, everywhere. If I could only remember my netbook, then I could use them everywhere, too. I never forget to put a book in my handbag, but I often forget the computer.

The hardcore reference books are the ones I use. They’re on paper, too, and sit near my desk. They range from dictionaries to encyclopedias. I have a volume on love and sex in the Middle Ages, two on Medieval folklore and several on science fiction and fantasy. I also have at least half a dozen herbals and several manuals of etiquette.

I think my least used reference book (of the paper ones) must be the rules to card games. My most used one is a nineteenth century dictionary. My current favourite is a nineteenth century guide to pronunciation of the English language.

4. A stack unto itself is my copy of Kellogg’s The Ladies’ Guide, a rather beautiful old tome. It sits next to the skull box (which contains Perceval, who is disarticulated) and some handmade lace, a few arrowheads from Hot Springs, Arkansas, and on a segment of a 1930s wedding obi. Kellogg is preachy and needs keeping under control. Between the arrowheads and the skull, civilisation is maintained.

5. The corridor is a transit zone and contains no books. The laundry and the bathroom are also transit zones. They are officially boring.

6. The library.

The library is the room with the most books. The only books that stack in the library are the five hundred or so patiently waiting their turn for shelf space. It was the spare bedroom until my visitors rebelled against sleeping in the margins between bookshelves. Those visitors who enjoy sleeping on book-infested carpet announce to their friends “I slept in L-space last night.” L-space doesn’t fit neatly inside items 6-9, but that’s all the space I’m devoting to it.

7. Fiction

I can’t talk about my fiction in just one sub-heading in just one essay. Three walls of bookshelves stacked to the ceiling and without an inch of spare space are not summarised so lightly.

Also, Thomas Hardy and George Gissing are dignified. Robertson Davies thinks he is. I’m not sure they’d appreciate being discussed in too close proximity to some of the other writers populating my fiction shelves.

Also, how do I discuss Eleanor Farjeon and Ionesco and Alan Garner and Joan Aiken all in one breath?

8. Nonfiction

There are only two giant shelves of nonfiction. This isn’t because I don’t like nonfiction. It’s because I’m a cheat.

Nonfiction doesn’t include herbals or Judaica because both of those belong with my cookbooks. Non-fiction doesn’t include Arthuriana, because that belongs with my Medieval Arthurian collection which belongs (you guessed it) with my cookbooks.

Nonfiction doesn’t include any history before 1800. History before 1800 doesn’t belong with my cookbooks. It belongs in my bedroom where I can access it at any time and where no-one else can see things and say “Gillian, I’ll just borrow this.” My versions of the Pseudo-Turpin Chronicle are not part of my lending library and I shall defend them stoutly with my corn tooth sickle (which I keep near the cookbooks, of course, because those cookbooks need defending most).

Nonfiction is everything that’s not cookbooks, Arthuriana, Judaica, Medieval, Renaissance, womenstuff… this list is getting exhausting. It’s alphabeticised by author, which is the main thing. I should just call it “Everything else,” but “Nonfiction” makes it sound as if I know what I’m doing with those two enormous shelves.

9. There’s a shelf hidden in my sorting bookshelf (where I keep those books I haven’t yet put away, for whatever reason, but that really ought not be stacked) and it has books and etceteras by me. Over time, the etceteras diminish and the books multiply. It’s still a very small shelf hidden in a sea of books.

10. The heart of the addiction

Epic legends, romances, chronicles – all Medieval. Modern editions. Modern works about them. A complete Pepys. Kemble’s promptbooks (editions of Shakespeare). A few volumes of the nineteenth century Parliamentary records relating to the British colonies now called Australia. I could list volumes for ages and every one of them would be interesting. They’re select and special and wonderful and… most people would call the room they’re in a bedroom. It’s more books than bed, but there is indeed, a bed and I do sleep on it. I try not to sleep on books.

The trouble with writing a list of ten things is that the numbers run out before one has even begun. I haven’t even talked about the books I haven’t yet met. Some of them are clamouring to join my library, and yet they don’t fit in this list. I’ll do another list, one day, of books I yearn to meet. I’ve already done a list (on my blog) of the piles of books waiting to be read or written about or returned or dealt with severely. And I’m not going to get started on the many volumes on loan to friends (for my library is also a circulating library, payment in dark chocolate).

All these things are important. My life is books: books are my life. Right now, though, my booklife has probably outgrown my two-bedroom unit. I just need a few more rooms and my life would be perfectly ordered.

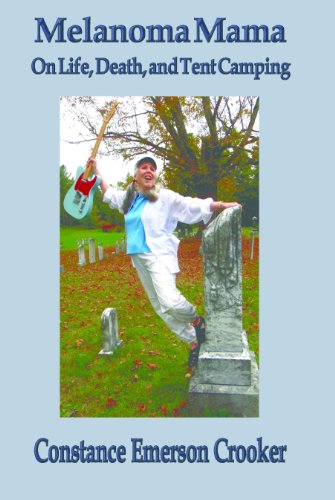

Memoir, Cancer, And Tent Camping: My Friend Connie

When a friend or family member is diagnosed with cancer, the effects ripple through the community. If we and our friend are relatively young, we may feel shock but also a sense of insulation. We have not yet begun to consider our own mortality, or the likelihood of losing our peers to accident or one disease or another. It hasn’t happened to us yet and the odds are still in our favor, particularly if we don’t smoke or drive drunk, we exercise and eat many leafy green vegetables. As the years and the decades go by, most of us will see an increase in morbidity if not mortality in our friends. They – and we – may develop osteoarthritis or Type 2 diabetes, high blood pressure, high cholesterol, all those common ailments of aging.

Some of us will get Covid-19. Some of us will get cancer.

When my best friend, Bonnie, was diagnosed with ovarian cancer, she was the closest friend I had who had cancer. Since then, other friends have been diagnosed and some have died; Bonnie died in 2013 (peacefully, at home). One of the things Bonnie did way back when was find support groups for women with cancer. Maybe it’s a holdover from the consciousness-raising groups of the 1970s, but it’s practically a reflex: whatever is going on in your life, you grab a bunch of women to talk it through. Do men do this, too? If so, it’s a secret from me.

It turned out that a cluster of women who were at college with us at the same time and who still lived in the area wandered through these groups at one time or another, or were otherwise associated with this community. Some have also died, some weren’t doing too well the last I heard, and some are thriving. One of those I lost was my friend, Constance Emerson Crooker.

Connie and I weren’t close in college, but it was a small school and everybody pretty much knew one another in passing. She wasn’t an avid folk dancer or a Biology major like me, but she and Bonnie stayed in touch so I’d hear about her from time to time. Connie was one of those who stepped up to the plate in Bonnie’s final weeks, and I was not only grateful for the extra and very competent pair of hands but for the chance to get to know her better.

Connie was a long-term melanoma survivor, a “late-stage cancer patient,” and made no bones about being one of the lucky ones.

One of the things Connie did was to go tent camping across America. Another thing was to write about it and her cancer. I slowly read and savored her memoir, MelanomaMama: On Life, Death, and Tent Camping. Tent camping does not rank high on my list of favorite things to do. I didn’t grow up camping, and I’m poor at it at best. But as I wended my way through her breezy story-telling, I realized it didn’t matter whether it was tent camping or ice skating or tango dancing (which Bonnie did, clear through the week she went on hospice) or anything else that gives us intense joy.

One of the things Connie did was to go tent camping across America. Another thing was to write about it and her cancer. I slowly read and savored her memoir, MelanomaMama: On Life, Death, and Tent Camping. Tent camping does not rank high on my list of favorite things to do. I didn’t grow up camping, and I’m poor at it at best. But as I wended my way through her breezy story-telling, I realized it didn’t matter whether it was tent camping or ice skating or tango dancing (which Bonnie did, clear through the week she went on hospice) or anything else that gives us intense joy.

William Blake wrote that if a fool would persist in his folly, he will become wise. I think that if we’re blessed to have enough time and reflection we can move through the shock and terror and sheer awfulness to some other place, one of “sucking the juicy joy out of life.” Which is why Connie’s tent camping spoke to me and I’m grateful she wrote her book.

When something awful happens to us or when we at last glimpse it in the rear-view mirror, many of us want to write about it. If we’re fiction writers, we use our imaginations to spin out stories in our preferred genre. A huge weight, a pressure of all the intense experience, the fear, the relief, the unhealed and oozing wounds, cries out for us to make sense of the whole thing. That’s one of the things that fiction does, and often it does it much better than straight memoir narrative. Fiction requires emotional coherence, at least genre fiction does. I make no promises about literary or experimental stuff. We think, If I could just nail this down in a story, it would make sense. I understand that longing, that temptation, and at the same time, in my own life, I’ve had the good fortune to pay attention to my gut feeling that I wasn’t ready. Maybe I’ll never be ready to “tell my story.”

But Connie was and she did, with wit and the ferocious clear-sightedness of one who knows she has been reprieved and what it has cost her. Some parts are travelog, some parts are survivalog, some are the observations of an intelligent, thoughtful person who has had a long time to decide how she wants to live each day. I couldn’t read very much of it at a time; it was too “chewy,” too emotionally dense. I needed to reflect on what she shared and what it meant in my own life.

In Connie’s writing, I recognized something quite different from the impulse to tell our story to make sense out it. It was the even more powerful need to take what we have suffered and have it make a difference. Have our lives make a difference.

“Hey world,” she seems to be saying, “I was here. Me, the only Connie there is or will ever be.”

“So now, I’m back to scans every three months. Watch and wait. Watch and wait. Wait for the pink and turquoise sneaker to drop. But I keep enjoying my miraculous recovery.

“When I say miraculous, I don’t mean a conventional miracle. … It’s miraculous that a Monarch butterfly can wing its way from Canada to one small patch of breeding ground on a Michoacan hillside. It’s miraculous that a black hole’s sucking gravity can pull everything, including light into is gaping maw. It’s miraculous that there are billions of stars in our galaxy and billions of galaxies in our universe…

“And I’m still here, gazing with wonder at it all.”

And sharing that wonder with us. Thanks, Connie, wherever you are tent-camping now.

Not a Fairy Story

I’m researching fairy tale retellings right now, so I want to start this post with Once Upon a Time. The story has a fairy tale element to it. It starts with a dream and ends with a happy surprise. It is, however, no fairy tale. Let me start it with the right words anyhow, because I can.

Once Upon a Time I had a dream. It was only a little dream. I woke up with an image from it so firmly imprinted into my vision memory, that, even before I had coffee, I went to my computer. I looked to see if I could find a picture of Io, because my dream was looking up at Io through an old telescope and seeing it as if it were our moon.

I found the picture almost immediately. Io looked the way my mind had dreamed it. I don’t remember if I took time for coffee, or if I wrote the story immediately, but by the end of the day I had a first draft of a story set in a far-distant planet, where a society re-enacted the eighteenth century.

I was chatting with a friend and told her about it. She read my draft. Then she told me her dream, which was to run a magazine. I let her have my story to use to build that magazine. She set up the organisation and edited everything and I and a couple of other friends built a world writers and artists could play in. That world was New Ceres. My story was its backbone and its heart, but it was never published. Life got in the way.

I took my version of New Ceres because I had new dreams about what could happen on that planet. Alisa took hers and she published a lovely anthology. She then started a publishing house and that publishing house has put out amazing book after amazing book. I watch to see where her dreams taker her next, because they’re always to fascinating places.

My dreams took a while to realise. First, I wrote them into a novel. An editor from a well-known science fiction press asked if I could send it to him. Whenever I asked about how he was going with it, I was told that it would be read the next week, that it was a priority, that I should not worry. Eight years later I took my manuscript back, and resolved to try elsewhere.

The novel was accepted somewhere else almost immediately, but that publisher imploded. Another publisher took it on. They asked one of my favourite artists to do the cover and he built (literally, built) a scene from the novel, and photographed it. A street from New Ceres lives in the Blue Mountains.

My novel was released straight into the first COVID inversion, where no-one looked for new novels by small press on the other side of the world. It was going to be celebrated at WorldCon in New Zealand. New Zealand is so close and so friendly and… the pandemic changed that, too. At least, I thought, it was finally published. I could close that chapter on those dreams and move on. Its final name was Poison and Light. Here, have a link to it. Admire the cover.

Tonight I had news about the novel I thought no-one could read because all the publicity and distribution were hit so hard by the pandemic that it simply wasn’t very visible. It’s been shortlisted for an award.

In that short-list are novels by wonderful writers whose work was issued by that first publisher. The editors won’t remember the eight years I had to wait, nor the emails that went unanswered in the last year, when I tried to find out what was happening. I remember. And now, finally, I know that the initial request to see the novel was serious. That it was an unlucky novel, but not one that was poorly written. And that readers are finding it, despite its travails.

I shall dream again tonight of that acned moon. And, finally, I will move on.

Goodness, Sweetness and just a touch of ratbaggery

Firstly, let me wish you all a happy and healthy and good and sweet New Year.

Rosh Hashanah starts very, very soon in Australia (I’ve put a delay on publication, so that it’s on Monday for most of you, but it’s already Monday afternoon here) and I’m furiously trying to get everything done in time. Lockdown, oddly, makes everything harder. If you’d asked me a few years ago, I’d have said “But of course it makes things easier.” I have apple and I have honey and I have mooncake in lieu of honeycake. I’m meeting my mother and her BFF and one of my BFFs online in a bare few minutes. My friend is a cantor and we’re going to have some music.

What makes this Rosh Hashanah special is my friends. One friend found me an apple. Another found me some honey. A third went to considerable length to get me mooncake. Even though I’ll be alone… I won’t be alone.

The downside is the number of people who want things from me today and tomorrow (sorry, but I can’t do these things) or, worse, the half-dozen different people who, just this week, have sent me invitations or reminders for events on my Day of Atonement.

To be honest, I’m not that observant. The more difficult people become around me because I’m Jewish, however, the more I stick to my special days. Holding gorgeous science fiction events (three of them! three different organisations!) on my holiest of holy days will make me stick to what I was taught as a child and even to fast and to pray. This has been the case ever since primary school. So many people have wanted me to be less Jewish or even not Jewish at all, and every time they express this or encourage me to be Christian or to eat pork or simply to work after sunset on days like today… I discover my Judaism all over again.

I do wonder what my religious views would be if I didn’t encounter antisemitism so often, or the limited toleration that I’m facing now. That limited toleration means that I make my mother happy, by doing the right things. This is not a bad outcome.

Whatever you believe or don’t believe, celebrate or don’t celebrate, please have a wonderfully good and sweet year. For anyone who, like me, will be fasting (at least as much as the doctor permits) then well over the fast. And for all of us, may we get through this pandemic well and safely and emotionally intact.

My Life in Dogs

I live with a geriatric half-Dalmatian former-athlete dog. She is sweet and stubborn and ridiculous… and approaching the end of her sell-by date. I had not thought to see my own mortality mirrored in my dog, but there it is. She’s not my first dog, but for a variety of reasons I didn’t get to see my earlier dogs age.

I live with a geriatric half-Dalmatian former-athlete dog. She is sweet and stubborn and ridiculous… and approaching the end of her sell-by date. I had not thought to see my own mortality mirrored in my dog, but there it is. She’s not my first dog, but for a variety of reasons I didn’t get to see my earlier dogs age.

When I was seven and away at my school’s spring camp for a week, my parents had some friends over for dinner. As a hostess gift of sorts they brought… a beagle puppy. They had stopped at a gas station the week before, and found a litter of orphaned pups in the ladies’ room. They spent the next week distributing these tiny animals who were really too young to have left their mother to all their friends. This included my parents. I suspect my mother greeted this new addition to the household with mixed feelings. She wasn’t anti-dog, but she had two small children and here was another lifeform to be responsible for. By the time I suspect she was thinking that a beagle puppy was one lifeform too many, I got home from camp Continue reading “My Life in Dogs”…

Raised in a Barn: A War on the Front Forty

My father was born to be a king. Or at least lord of the manor. He had the eccentric manor and the acreage. And when some friends of mine from the Society for Creative Anachronism came to visit, with the express purpose of deciding whether the front lawn would be a good place for a war, Dad was all in.

By the front lawn, I mean the approximately 20 acres of pasture across the road from the Barn, proper. When my parents bought the barn, 180 acres of land came with it: the front 20 (often referred to as the front forty, perhaps because of the alliteration) separated from the Barn and the rest of the mountain by a county road, and the 160 acres around and behind the barn, most of which was hilly, forested, and not much in the way of farmable. The front 20 was rather rolling, and ran down about a quarter of a mile to the Housatonic River, storied and sung in my youth for its horrid pollution. My brother and I had never stuck a toe in it for fear of having it dissolve.

My SCA friends returned to their barony and pitched the idea of a battlefield event, and the War of the Roses was born. I was kept apprised of the planning (since I was more or less the intermediary between my parents and the machineries of war), and some basic ground-rules were set: the war was across the road from the Barn, but people were permitted to come up and draw water from the hose spigot outside the studio door. Digging a hole in which to roast an ox (my father’s face was incandescent at the thought) was okay, and smaller fires likewise, so long as they were rigorously tended. This area for parking. This area, marked out with pennons, for the battle, and That area—essentially the rest of the field—for setting up temporary residences.

Of course I made my parents suitable garb. My mother didn’t want anything particularly fancy—”your basic medieval schmatta,” as she put it. But my father… I told him to find a painting from any period from 1000-1600 and I would do my best to make the clothing depicted for him. Of course he went for Henry VIII. My father, barrel chested with knotty, muscular calves that would have made the Tudor court swoon, was made for this. I made him the outfit, and he wore it for the weekend and…did I saw born to be a king? Yeah, like that.

My recollection of the whole weekend is rather kaleidoscopic: I bounced back and forth between the camp and the Barn (and slept in my own bed). The fire over which the ox (well, the half-cow) was to be roasted wasn’t lit early enough, which meant that the meat wasn’t actually cooked until half past 10 that evening. The battle itself was spectacular—a series of individual fights first, followed by a melee, all framed against a sky full of gray clouds. Despite the overcast of the day it was warm, bordering on hot, and after the war was over, some of the combatants took themselves down to the river to skinny dip. Apparently the river had been cleaned up a lot while I was living elsewhere: no one dissolved or emerged from the water writhing in agony (and at the following year’s war skinny dipping was a feature, not a bug: the day was hotter and sunnier, and immediately after the battle the banks of the Housatonic were teeming with naked warriors).

Possibly my father’s favorite moment of the weekend came on Saturday evening. People camped pretty much where they wanted, and one young woman had pitched her tent three quarters of the way down the field, just before the river bank. And she started having belly pain. Among other things, my father was a member of the volunteer ambulance squad, and a qualified EMT. Someone found me and reported a woman in pain, and I charged up to the Barn, where my father had retired for the evening was wearing his civvies. Within a minute of my outlining the problem Dad had his kit in the car, slapped the green flasher on the roof, and tore down the hill to the campsite. “Hot appy!” he announced, and judged this was not the time to wait for the ambulance. He loaded her into his car and took her off to the local hospital, where her appendix was removed just in the nick of time.

The next day the Baron and Baroness of the presiding Barony made a presentation to my parents, and they were roundly huzzahed. I think my mother enjoyed it, in an “I’m just here to watch the young folks being crazy” sort of way. But Dad was in his element: how often do you get to be the Lord of the Manor, Rescue the Maiden (from the fearsome Appendix!) and dress like a king?

Fight the (Sedative) Power

Until I was about five, I could not breathe through my nose. Literally. If I tried to hum I would run out of air and have to gulp for breath before I turned blue and fell over. I had that expression common to the adenoidally-impaired: a sort of gape that might have been cute on a five year old, but makes you look stupid at 6. My adenoids and tonsils were so persistently swollen that the only thing to do was to yank them.

Me being, even then, me, I was hugely excited about this. Going to the hospital and staying over night. An operation! Whee! So the day of the event I was delivered to the hospital first thing in the morning, checked in and dressed in hospital togs, and given a sedative by suppository (I was not thrilled by this–no one had said anything about having things shoved up my butt, but I was an easy-going child, and it was all so exciting!).

It was so exciting, in fact, that when the sedative began to do its job, I fought it off. Continue reading “Fight the (Sedative) Power”…