Today I have written a great deal. That great deal added up to a very short story and a few hundred words of non-fiction. It just felt like a great deal. I suspect this was because I am surrounded by autumn storms. Everything feels like a great deal when one is surrounded by storms.

Normally I walk my bookshelves to find you an interesting book to talk about. Because I have met two whole deadlines today (two!) I thought I’d take the easy way out and write about the nearest book to me. I forgot that I had six of my own books in reach because I was talking about them to someone. And yet, the weather is about to break (I have a very handy weather sense) and I need to finish writing this before then because when there is a storm literally overhead, I doubt I’ll be writing to you about interesting reading.

I’m taking the interesting route. On my computer I have – like so many of us, these days – an elibrary. I’m going to open a folder at random. The folder are labelled with the alphabet, except the historical food one, which is labelled ‘Cooking.’ Just typing about that particular heading led me straight into the Cooking folder, so let me find you a cookbook or historical food book of particular interest.

I opened the folder and was curious about one that wasn’t properly labelled at all. It proved to be a transcription of the 1596 The Good Huswifes Jewell. Just the opening is delightful, and if I find it delightful then you’re stuck with it. Let me give you that opening, in all its gorgeousness.

The Good Huswifes Jewell “Wherein is to be found most excellend and rare Deuises for conceites in

Cookery, found out by the practise of Thomas Dawson.

Wherevnto is adioyned sundry approued receits for many soueraine oyles, and the way to distill many precious waters, with diuers approued medicines for many diseases.

G.STEEVENS

Also certain approued points of husbandry, very necessary for all Husbandmen to know.

Newly set foorth with additions. 1596.

Imprinted at London for Edward White, dwelling at the litle North Doore of Paules at the signe of the Gun.”

If ‘Paules’ is St Paul’s Cathedral, then Edward White, the publisher, was in a part of London that had been book and scribe central since the Middle Ages. If you were in London in the thirteenth century and needed a notary in a hurry, the back of St Paul’s was the place.

I’m so tempted to simply let my mind rove in that district in the Middle Ages, and contemplate where I would buy parchment or commission illuminations, but this is a cookbook and my mind must remain resolute (the impending storm insists). Let me give you a recipe from the book, then. Everyone needs boiled chicken once in a while, and I’ve not made this recipe, so it’s a useful one all round:

To boile Chickins.

Straune your broth into a pipkin, & put in your Chickins, and skumme them as cleane as you can, and put in a peece of butter, and a good deale of Sorell, and so let them boyle, and put in all manner of spices, and a lyttle veriuyce pycke, and a fewe Barberies, and cutte a Lemman in pecces, and scrape a little Suger uppon them, and laye them vppon the Chickins when you serue them vp, and lay soppes vpon the dish.

I read this as using broth – I’d use chicken bouillon, because I always do when things are otherwise not clear. Boiling chicken in a broth sounds rather good, actually. Different broths would infuse it with different flavours. Butter and sorrel combined give a very smooth texture and flavour, and the verjuice might be to make it be not too unctuous. Barberries I love and have some on hand: they would add a fruitiness and also cut that unctuousness. In fact, I have most of the ingredients on hand. I’m just missing the chicken, the sorrel and the verjuice. Also, I’m missing bread. Without bread I can’t make sops. It’s just as well, really, because it’s 11.30 pm here and not the time to be making a chicken recipe.

In fact, it was a really bad idea to open that file and find you a recipe. I want to cook! Instead of cooking, let me find you another recipe from 1596. If you’re inspired to make either of these, I’d love to know how it went and, if you take pictures, it would make me very happy to see them.

Because most of you are heading for summer and the fruit is just beginning to arrive (we’re heading for winter and I’m eating persimmon and pomegranate and papaya while I can) how about a recipe that requires summer fruit? This one has fewer terms that need explaining, which is a bonus. I never know how much to translate, because it’s perfectly modern (Early Modern – I was making a bad joke) English. It all depends on how much cooking you’ve done and what kind of cooking. Stoves as we know them weren’t around in the late sixteenth century. A great deal of cooking was done over an open fire with a wonderful set of cooking equipment. This preserved fruit recipe, for example, uses the head of a pot covered by a plate, which is a very nice way of making sure the fruit stays whole.

To preserue all kinde of fruites, that they shall not breake in the preseruing of them.

Take a platter that is playne in the bottome, and laye suger in the bottome, then cherries or any other fruite, and so between euerie rowe you lay, throw suger and set it vpon a pots heade, and couer it with a dish, and so let it boyle.

Now I’m dreaming of apricots cooked this way and eaten with clotted cream.

I need to sign off before I start cooking. I so often do this I open an historical cookbook and then end up making something and not finishing my work. I shall leave you with one last recipe and no explanation whatsoever, and then I’ll finish all that must be done before this impending storm ceases to impend. Then I shall sleep and dream of preserved apricots served with clotted cream.

This last recipe is not quite a trifle as we know it today, but it is, nevertheless, kind of an ancestor to the Queen’s Jubilee dish that so many of my British friends have been making. Only kind of. I know its 18th century descendants and they’re all drinks. I am only missing the cream for this trifling dish. I would turn into something strange if I eat this at midnight, which is the precise time it would be ready, so I’m lucky I’m missing that cream (when you make it yourself, remember than thick cream has no gelatine or other thickener – it should dollop when you spoon it into the dish and must be at least 45% fat):

To make a Trifle.

Take a pinte of thicke Creame, and season it with Suger and Ginger, and Rosewater, so stirre it as you would then haue it, and make it luke warme in a dish on a Chafingdishe and coales, and after put it into a siluer peece or a bowle, and so serue it to the boorde.

PS While there is a place called West Wittering in the UK, and also one called East Wittering, alas, there does not appear to be one called Much Wittering. I might have to invent a fictional town, in Australia but with English tendencies.

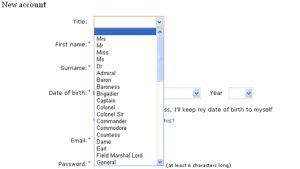

I was raised informally; the teachers at my (progressive) grade school were addressed by there first names; I called my parents’ friends by the first names as well–no Aunt or Uncle unless they insisted (only one person–my father’s accountant’s wife–insisted). This doesn’t mean I didn’t treat them respectfully, but it does mean that I grew up expecting a certain amount of reciprocal respect. When we moved and I went to a more traditional school, I called the teachers Miss/Mrs/Mr. I did ask once why we didn’t call all the female teachers Ms, and was told without irony it was because they didn’t have that many young unmarried women on staff. Okay then.

I was raised informally; the teachers at my (progressive) grade school were addressed by there first names; I called my parents’ friends by the first names as well–no Aunt or Uncle unless they insisted (only one person–my father’s accountant’s wife–insisted). This doesn’t mean I didn’t treat them respectfully, but it does mean that I grew up expecting a certain amount of reciprocal respect. When we moved and I went to a more traditional school, I called the teachers Miss/Mrs/Mr. I did ask once why we didn’t call all the female teachers Ms, and was told without irony it was because they didn’t have that many young unmarried women on staff. Okay then.

Certain shows (I’ll spare you the list) lodge deep under my skin–The Music Man, which I saw last week on Broadway, being one. I grew up with the cast album (Robert Preston and Barbara Cook) and the film (Robert Preston and Shirley Jones). I had never seen it staged, however, so when the opportunity arose to see a revival with Hugh Jackman and Sutton Foster, I leapt at it, credit card in hand. I want first to say that I liked it a lot. That being said…

Certain shows (I’ll spare you the list) lodge deep under my skin–The Music Man, which I saw last week on Broadway, being one. I grew up with the cast album (Robert Preston and Barbara Cook) and the film (Robert Preston and Shirley Jones). I had never seen it staged, however, so when the opportunity arose to see a revival with Hugh Jackman and Sutton Foster, I leapt at it, credit card in hand. I want first to say that I liked it a lot. That being said…