It doesn’t matter what I do, Merlin appears, as if by magic. He even appeared over Christmas, as one of his stories has some very interesting parallels with a Jewish version of the life of Jesus. This led to (as night leads to day) me looking for the first Merlin-like book I could see on my shelves. It was a textbook.

Some textbooks discourage reading. Others say “Read this bit and then that, then go find the works I’ve introduced to you.” Merlin through the Ages (ed R.J. Stewart and John Matthews) is definitely one of the latter. I’ve never read the whole book. I have, however, read some of the works extracted. All the Medieval ones and just enough of the others so that I can (occasionally) feel as if I’m almost educated. I bought it when I was teaching this kind of subject and, even though I’ve no space for more books, I can’t get rid of it because… what if I need it again?

The reason I haven’t read it from beginning to end is partly because the type is tiny and partly because the table of contents is overwhelmingly male, but mostly because I have favourite Merlin stories elsewhere and every time I open this book (even when I was using it for teaching) I would have put it down within fifteen minutes. I didn’t put it down because the book was dull, but because I kept wanting to check something else. At least half the time, that something else was T.H. White. There is no extract from T.H. White in this book, you see, and I felt I owed him a re-read.

There was one other thing I did with this book. I came to it too late for it to be a source book for my first novel. Illuminations was based on medieval versions of a whole bunch of stories we take for granted, so this volume would have been perfect except… I’d already written a large chunk of the novel. I used Merlin through the Ages to remind myself of where I’d been in my research.

Just considering this takes me back to the actual research for the bits that were borrowed from the Middle Ages. I wandered through the stacks at Fisher Library and grabbed all the things I wanted to read that I had no real excuse to read, and I read them for my novel. To this day I don’t know why I thought that reading nineteenth century editions of Medieval stories was a holiday from reading all kinds of editions (and a bunch of manuscripts, not edited) of Medieval stories.

The story that got me started was Benedeit’s The Voyage of St Brendan, which I studied, word by word as part of my Masters degree. My edition of this is still sitting on the bookshelf. It was edited by Short and Merrilees, both of whom had the misfortune of teaching me. I might hand the Merlin compendium to someone who wants it more than I do and has better eyesight, but my Benedeit is going nowhere. I even slipped a quiet tribute to my teachers and to Benedeit into Illuminations.

I lard my novels with secret messages to books I love. This is, I think, a very good thing, even if I’m the only one who knows they’re there.

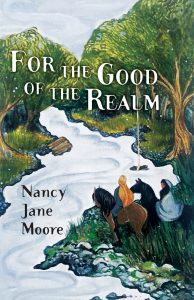

Here’s my review of For the Good of the Realm, by Treehouse Writer’s own Nancy Jane Moore (Aqueduct)

Here’s my review of For the Good of the Realm, by Treehouse Writer’s own Nancy Jane Moore (Aqueduct) Black Sun, by Rebecca Roanhorse (Saga)

Black Sun, by Rebecca Roanhorse (Saga)

House of the Patriarch, by Barbara Hambly (Severn House)

House of the Patriarch, by Barbara Hambly (Severn House)

The Glass Magician, by Caroline Stevermer (Tor). What a delightful tale, set in an early 20th Century world in which humans are divided into ordinary Solitaires, shape-shifting Traders, and ecology-minded Silvestri. The story focuses on Thalia, a magic performer, and her manager, Nutall, who’s acted as a parental figure after the deaths of her parents. When a rival stage magician gets them booted from their gig using a noncompete clause, their future looks grim. Then the rival turns up dead and Nutall is the prime suspect. To make matters worse, Thalia, who has always believed herself to be a nonmagical Solitaire, under the stress of a trick gone dangerously wrong, shape-shifts (“Trades”). Newly fledged Traders are not yet in control of their powers and become the prey of magic-consuming manticores. Now Thalia’s very life is at risk until she can master her magic, at the same time she’s determined to prove her mentor’s innocence and unmask the real murderer. The world and its characters are beautifully, charmingly drawn, with the effortless skill of a consummate storyteller.

The Glass Magician, by Caroline Stevermer (Tor). What a delightful tale, set in an early 20th Century world in which humans are divided into ordinary Solitaires, shape-shifting Traders, and ecology-minded Silvestri. The story focuses on Thalia, a magic performer, and her manager, Nutall, who’s acted as a parental figure after the deaths of her parents. When a rival stage magician gets them booted from their gig using a noncompete clause, their future looks grim. Then the rival turns up dead and Nutall is the prime suspect. To make matters worse, Thalia, who has always believed herself to be a nonmagical Solitaire, under the stress of a trick gone dangerously wrong, shape-shifts (“Trades”). Newly fledged Traders are not yet in control of their powers and become the prey of magic-consuming manticores. Now Thalia’s very life is at risk until she can master her magic, at the same time she’s determined to prove her mentor’s innocence and unmask the real murderer. The world and its characters are beautifully, charmingly drawn, with the effortless skill of a consummate storyteller.