A couple of years ago I witnessed a curious thing: as Emily-the-Moldavian-Leaping-Hound and I were crossing over the highway on our way to the dog park, I looked down and saw a pleasant looking mature woman walking her own dogs. As the dogs did what dogs do, the nice looking woman picked up their droppings in a plastic bag, all tidy. She then walked over to an SUV and left the tidy bundle of dog feces under the windshield wiper. Having done that, she walked away with her dogs.

Of course my response was: what the @N#*$!?!? What is the story there?

Being a writer, for me, is about trying to figure out why people do things. When I was small and encountered unkindness, I would tell myself stories that explained (if they didn’t justify) why the other person did something unkind. It wasn’t enough to say “that person is a big selfish meanypants” because it seemed to me unlikely that the person regarded himself or herself in that light. So what would justify, in their minds, being mean to me? I was not, I hasten to add, always successful in making sense of my fellow humans.

Still, to this day, when I encounter someone doing something I consider unusual, my novelizing kicks in. In the case above perhaps:

• the SUV belonged to the woman herself and she was putting the bag there until she could return to dispose of it.

• she and the SUV’s owner had a longstanding feud.

• she had a principled stand against gas guzzlers and this was her way of making a statement.

• she had a momentary psychic fugue and had no idea what she was doing.

• she had been taken over by an Evil Spirit and prompted to do something weird.

I could very likely write a story in which any of these things are true. The action I saw was not the climax of the story–it’s the beginning.

Next time you see one of your fellow humans doing something really…odd…consider it a writing prompt and see where it takes you.

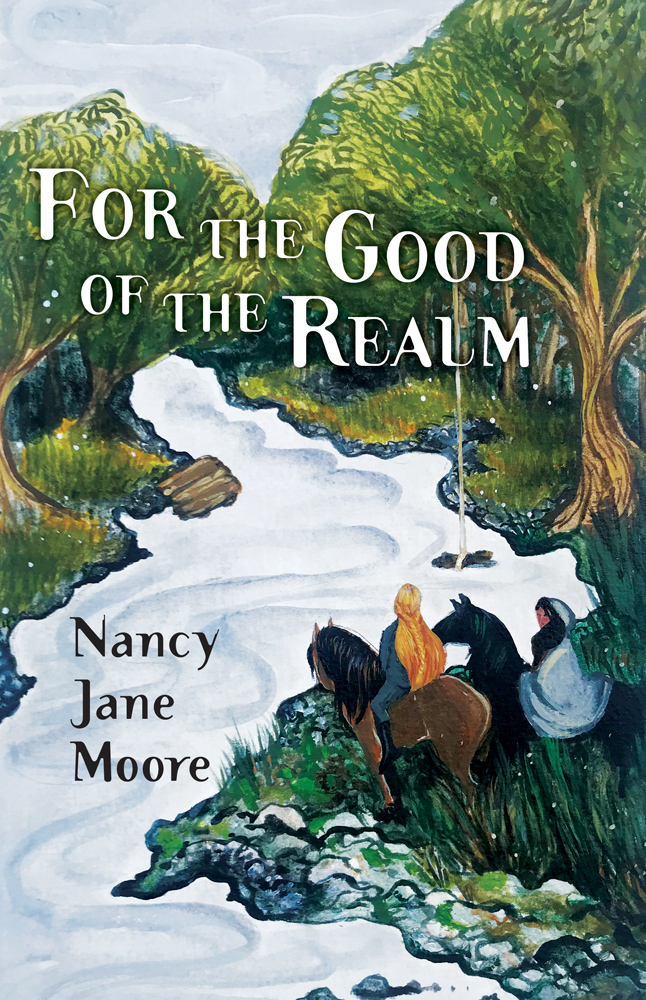

I just received editorial comments and a marked-up manuscript of the current novel from the editor. It’s such a joy to work with a professional who “gets it” and offers intelligent, insightful feedback. Editorial comments are quite different from critiques, by the way. At least, in my experience. While both can be valuable, the critiquer is essentially outside the story, jabbing at its shortcomings, whereas a good editor gets inside the story with the author, rolls up her sleeves, and says, “Let’s work together to make this book its best self.” And I have a great editor.

I just received editorial comments and a marked-up manuscript of the current novel from the editor. It’s such a joy to work with a professional who “gets it” and offers intelligent, insightful feedback. Editorial comments are quite different from critiques, by the way. At least, in my experience. While both can be valuable, the critiquer is essentially outside the story, jabbing at its shortcomings, whereas a good editor gets inside the story with the author, rolls up her sleeves, and says, “Let’s work together to make this book its best self.” And I have a great editor. It’s blackberry season, and as is my custom at this time, I went out this morning to pick from the brambles along our little country road. (We have our own patch, but the berries ripen later because it’s in a shadier place.) I try to do this early, when it’s cool and I’m not having to squint into the sun for the higher branches. As I picked, I thought about the story I’m working on (and currently stalled on 2 scenes-that-need-more), and also writing in general.

It’s blackberry season, and as is my custom at this time, I went out this morning to pick from the brambles along our little country road. (We have our own patch, but the berries ripen later because it’s in a shadier place.) I try to do this early, when it’s cool and I’m not having to squint into the sun for the higher branches. As I picked, I thought about the story I’m working on (and currently stalled on 2 scenes-that-need-more), and also writing in general.

Crossing genres is hot business these days: science fiction mysteries, paranormal romance, romantic thrillers, Jane Austen with horror, steampunk love stories, you name it. A certain amount of this mixing-and-matching is marketing. Publishers are always looking for something that is both new and “just like the last bestseller.” An easy way to do this is to take standard elements from successful genres and combine them.

Crossing genres is hot business these days: science fiction mysteries, paranormal romance, romantic thrillers, Jane Austen with horror, steampunk love stories, you name it. A certain amount of this mixing-and-matching is marketing. Publishers are always looking for something that is both new and “just like the last bestseller.” An easy way to do this is to take standard elements from successful genres and combine them.

Cities are palimpsests. Growing up in New York, I saw constant evidence of this: tear down a building and there would be a painted advertisement from the early 1900s, or the brick outline of an earlier neighboring building. Restaurants that were a feature of my childhood streets are barely a memory now: gone. In New York the only constant, really, was change.

Cities are palimpsests. Growing up in New York, I saw constant evidence of this: tear down a building and there would be a painted advertisement from the early 1900s, or the brick outline of an earlier neighboring building. Restaurants that were a feature of my childhood streets are barely a memory now: gone. In New York the only constant, really, was change.