I’ve been thinking about the Jewishness in my fiction. Bettina Burger and I are working on getting a handle on Australian and NZ Jewish speculative fiction, so, this week, the books being discussed are my own.

Firstly, I need to admit (alas) that I don’t think I’m related to Joel Samuel Polack, who wrote in the nineteenth century. Right surname, right religion, right region of the world, wrong family. I’m descended from the Abraham Polack who came to Melbourne in 1858, not the rather more famous one who came to Melbourne in 1824. I think Joel Samuel is from the earlier family. There are other writers in my family, but I’m the only one with this surname.

A subject that comes up a lot in my vicinity is why there aren’t more Australian SFF writers who publicly identify as Jewish. There are so many possible reasons, but I don’t want to give simplified explanations, especially about identity. One thing I do know is that, when I speak before a large audience, I often have Australians (so far no New Zealanders) coming up to me afterwards and admitting they are Jewish and asking, “But don’t tell anyone.” Some give the reason as personal safety, while others give no reason at all. Others identify with Judaism because of Jewish parents and grandparents but are not halachically Jewish and do not wish to claim Jewishness. In other words, it’s a very personal decision. Given the number of Shoah survivor families who are in Australia and given the small number of Jews outside Melbourne and Sydney (and that I am in Canberra) the decision not to be public about one’s identity is an important one.

I have been publicly Jewish my whole life. It’s caused me many problems and lost me many opportunities, but various family members let me know how important it was to them and family culture is important to me. One Moment in my life was when my great-uncle explained to me that if no-one did this, then things would be worse for those who had no option. I was (and possibly still am) very dutiful and was on so many committees and did so much stuff in response to the need for public understanding of Jewishness in order to prevent another mass murder. I was on committees and even gave advice to government Ministers at one point, which is why a chapter of Story Matrices has a letter from a minister saying it was fine to use the material.

Eventually I realised that I was not my great-uncle or my grandmother and that Gillianishly was a proper way of living a life. I finally wrote my Australian Jewish novel. I thought the whole world would change in 2016 because there was finally an Australian Jewish fantasy novel. When The Wizardry of Jewish Women was released, I kept a very close eye on its trajectory within the Jewish community, partly because I have a history of activity in the Jewish community (that family thing!). Not many people noticed. It was world-changing for me, however, and was shortlisted for a Ditmar, and ever since then I’ve worked through my fiction.

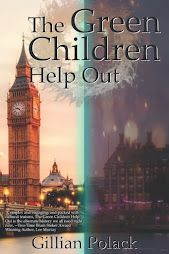

Ironically, I’m writing this post on the weekend when Ditmar award nominations are open (see addendum, if you’re curious) and I have another Jewish-themed novel that is eligible (The Green Children Help Out). Given COVID, it’s been more visible elsewhere than Australia, so I’m appreciating the irony of writing about my Jewishness in my fiction at this precise moment.

Sorry about the diversion. Back to Wizardry. I wanted a Jewish Australian #ownvoices novel. There are so many options for Jewish Australian #ownvoices, so I chose one very precise family and had a lot of fun exploring them. I was also reacting to the invisibility of Jewish Australian culture and the misuse of the Jewish fantastic. I still have issues about all these things, and one of these issues is going to be addressed in a story I wrote for Other Covenants, where I brought out my Medieval self to address the significant differences between Christianity and Judaism and that Christian interpretations of stories are not going to be the same as Jewish. But that’s in my future. Today I’m talking about the past.

Most Jewish-Australian speculative fiction writers are, for the most part, first or second generation Australian. They bring with them backgrounds from Europe, Israel, South Africa and the USA. My family arrived in Australia between 1858 and 1918. While much of it is European, one branch is from London.

Given the strength and cultural impositions from the White Australia policy and Federation, that London origin has impacted the family culture. Yiddish and Ladino had not been family languages for over a century until Yiddish was reintroduced into the generation after mine and until I learned to read a bit of (transliterated) Ladino.

Anglo-Australian Judaism is closest to UK Modern Orthodox Judaism in culture and much of the acquisition of Yiddish folkways and even Yiddish words in English came to the family through US popular culture. I have a US Catholic friend who knows far more Yiddish than I do, because she is from New York and Yiddishisms are part of her everyday English. While the family Chanukah tradition included a sung version of Ma’otsur, the Dreidel song was not acquired until the 1990s. I still don’t think of the Dreidel song as very Chanukah-ish. I didn’t react to not being from a well-known type of Jewish culture. I built my world from the inside: I intentionally use my Anglo-Australian Jewishness in my fiction, whether directly in The Wizardry of Jewish Women, or indirectly, for example as satire in Poison and Light. (The Chelm-equivalent jokes in Poison and Light came from my mother’s neighbour, who was from Chelm and who taught me Chelm jokes ie none of these statements are universal – culture is delightfully complicated.)

Older Australian Jewish culture holds very strong family cultures of university education. For my work specifically, this means that the Jewish history I learned through stories and through books in our (very bookish) home was placed in the wider context of Western European histories from my teens. I owe being an historian to being Jewish, I suspect.

While occasional members of my family were Shoah survivors and whole branches of the family were lost to the Holocaust, the young men in my corner of the family were in the Australian and British military (army and air force) during the war, and the most significant loss for those close to me was my mother’s youngest uncle, who was a bomber pilot. When addressing issues of war and loss, my approach is still Jewish (and still replays many issues relating to the Shoah) but deals with these matters from a different angle to the work of most other writers. Where Jane Yolen wrote Briar Rose, for example, I split my sense of what was lost into several parts and addressed some of them in The Time of the Ghosts, some in Poison and Light and others in The Green Children Help Out.

There were emotional and experiential gaps between Australian Holocaust narratives and my family’s experience. These gaps are very Australian in nature. Many survivors came to Australia because it was as far from Europe as it was possible to go. My family had been here for a generation or more when they made that difficult journey. The difference between their experience and my family’s understanding led to a different set of narrative paths. This is not true of all Australian Jews. Mark Baker, for example, writes Shoah narratives based on his own family background. He does not, however, write speculative fiction.

I did a little research about Australian Jewish fiction (in general, and also in YA, and also in historical fiction and in speculative fiction) a few years ago and I was greatly perturbed to discover that novels about the Shoah or Ultra-Orthodox life were acceptable, but that secular Australian Judaism was almost impossible to find in fiction. The only aspect of Jewish folklore or magic that was written about consistently was the golem. This is the main reason I wrote The Wizardry of Jewish Women (2016) and a sequel short story (that was published long before the novel) “Impractical Magic.”

Poison and Light (2020) and Langue[dot]doc 1305 (2014) are examples of my ongoing tendency to include appropriate elements of Jewish history and culture in types of novels where they’re normally entirely neglected. In Poison and Light, Jewish characters (all minor players in the story) have a different response to everyone else when the eighteenth century is re-invented on New Ceres, while Langue[dot]doc 1305 has a minor character whose experience of Judaism is of a kind, again, that’s seldom covered in fiction. The Time of the Ghosts (2015) has a major character who is Jewish and whose personal writing about historical events and her own life again, do not follow the standard stories Australians use when writing Jewish character and culture. The Green Children Help Out (2021), stories in Mountains of the Mind, (2019) and “Why The BridgeBuilders of York Pay No Taxes” (that Other Covenants story) are all set in an alternate universe where England has a significantly higher number of Jews. Once I learned how to start creating fiction with Jewish components, I was unable to stop.

And now you know…

Addendum:

For those of you who want to know about the Ditmars (Australian SFF awards – the Hugo equivalent, really), this is the information that came by email today via Cat Sparks. These are not my words – they’re the official information.

Nominations for the 2022 Australian SF (‘Ditmar’) awards are now open and will remain open until one minute before midnight Canberra time on Sunday, 7th of August, 2022 (ie. 11.59pm, GMT+10).

The current rules, including Award categories can be found at:

https://wiki.sf.org.au/Ditmar_rules

You must include your name with any nomination. Nominations will be accepted only from natural persons active in fandom, or from full or supporting members of Conflux 16, the 2022 Australian National SF Convention (https://conflux.org.au/).

Where a nominator may not be known to the Ditmar subcommittee, the nominator should provide the name of someone known to the subcommittee who can vouch for the nominator’s eligibility. Convention attendance or membership of an SF club are among the criteria which qualify a person as ‘active in fandom’, but are not the only qualifying criteria. If in doubt, nominate and mention your qualifying criteria.

You may nominate as many times in as many Award categories as you like, although you may only nominate a particular person, work or achievement once. The Ditmar subcommittee, which is organised under the auspices of the Standing Committee of the Natcon Business Meeting, will rule on situations where eligibility is unclear. A partial and unofficial eligibility list, to which everyone is encouraged to add, can be found here:

https://wiki.sf.org.au/2022_Ditmar_eligibility_list

Online nominations are preferred

https://ditmars.sf.org.au/2022/nominations.html

Once I got reading under my belt, I couldn’t do enough of it–books, stories, cereal boxes, comic books. I gobbled up story like I was starving for it, initially uncritically, but fairly soon starting to think about why stories worked/didn’t work for me. In this I had a partner: my brother Clem. He and I amassed a comic book collection of perhaps 2000 well-worn, repeatedly read comics–most, but not all of them DC (the home of Superman and Batman). Clem and I haunted the smoke shop at the corner, where the new comics came in every… I think it was Tuesday… and conspired over which one of us would buy which. We took them home and read the them and then we talked over them. Clem, a far better artist than I will ever be, led the way in discussing the art. One of our favorite riding-on-the-subway games was to identify people who looked like they were drawn by specific artists.

Once I got reading under my belt, I couldn’t do enough of it–books, stories, cereal boxes, comic books. I gobbled up story like I was starving for it, initially uncritically, but fairly soon starting to think about why stories worked/didn’t work for me. In this I had a partner: my brother Clem. He and I amassed a comic book collection of perhaps 2000 well-worn, repeatedly read comics–most, but not all of them DC (the home of Superman and Batman). Clem and I haunted the smoke shop at the corner, where the new comics came in every… I think it was Tuesday… and conspired over which one of us would buy which. We took them home and read the them and then we talked over them. Clem, a far better artist than I will ever be, led the way in discussing the art. One of our favorite riding-on-the-subway games was to identify people who looked like they were drawn by specific artists.

Certain shows (I’ll spare you the list) lodge deep under my skin–The Music Man, which I saw last week on Broadway, being one. I grew up with the cast album (Robert Preston and Barbara Cook) and the film (Robert Preston and Shirley Jones). I had never seen it staged, however, so when the opportunity arose to see a revival with Hugh Jackman and Sutton Foster, I leapt at it, credit card in hand. I want first to say that I liked it a lot. That being said…

Certain shows (I’ll spare you the list) lodge deep under my skin–The Music Man, which I saw last week on Broadway, being one. I grew up with the cast album (Robert Preston and Barbara Cook) and the film (Robert Preston and Shirley Jones). I had never seen it staged, however, so when the opportunity arose to see a revival with Hugh Jackman and Sutton Foster, I leapt at it, credit card in hand. I want first to say that I liked it a lot. That being said… Inspired by Nancy Jane Moore’s piece last Friday, I downloaded The Baby on the Fire Escape.* I’m working my way through it–it is wonderfully written, dense and thoughtful, with much to digest. As Nancy says, it’s about mothers as creators, about the ways that women have found to do creative work, sometimes in the interstices of motherhood, sometimes by turning their backs on motherhood, sometimes working with support, sometimes going it alone.

Inspired by Nancy Jane Moore’s piece last Friday, I downloaded The Baby on the Fire Escape.* I’m working my way through it–it is wonderfully written, dense and thoughtful, with much to digest. As Nancy says, it’s about mothers as creators, about the ways that women have found to do creative work, sometimes in the interstices of motherhood, sometimes by turning their backs on motherhood, sometimes working with support, sometimes going it alone. I think my friends and family assume it’s a phase. They are always trying to give me books after they’ve finished them. This one will convince you to read adult books again. Nope.

I think my friends and family assume it’s a phase. They are always trying to give me books after they’ve finished them. This one will convince you to read adult books again. Nope.